How the uranium boom went bust but still led to one of the most vibrant towns in Utah

Charlie Steen’s rags-to-riches story has been told so many times it’s reached legend status: how he prospected unsuccessfully for two years in the Moab area before deciding to call it quits, and in testing his very last core sample, he discovered the high-grade uranium ore that made him rich and sparked a prospecting fever that forever changed the small western town of Moab, Utah.

Uranium had been part of the area’s economy for decades before Steen’s discovery. While Steen is known as the “Uranium King,” Howard Balsley, a community leader who lived from 1886 to 1982, is known as “the father of uranium” in Grand County. In a 1969 speech to the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers, Balsley recounted his ups and downs in the industry. It was subject to the fluctuations of supply and demand, but Balsley managed to stay in the game and make a profit.

Balsley funded the discovery of some of the area’s uranium deposits through an arrangement called “grub-staking”: Balsley bought the supplies that a prospector needed to live on and to explore and search for deposits, and the two split the profits from whatever was found.

In 1915, a cowboy-turned-miner named Charles Snell told Balsley about a dream in which he saw a yellow circle in a block of sandstone in the “upper Cane Springs” area.

“I never had much faith in dreams, but this man was so sincere, and I knew him to be honest and truthful, so I bought for him everything needed for his proposed prospecting expedition,” Balsley said. About ten days later, Snell reported that he had found the yellow circle he’d dreamed about.

“Later, we located more claims in that area and the property has produced a vast tonnage of real good uranium-bearing ore through the years — more than a million dollars worth, in fact!” Balsley wrote.

Early on, minerals found in uranium ore were used to make colorants for pottery and glass; in the production of steel and steel alloys; in research; and in experimental medical treatments.

After World War II, the federal government had a keen interest in developing nuclear weapons. In 1945, the government froze the sale of all land that contained uranium. In 1946, the federal Atomic Energy Commission was created, and it controlled the uranium industry. The Cold War was on and the agency wanted to boost domestic uranium production. In 1951 it offered a $35,000 discovery bonus for finding new uranium deposits and fixed the price of the mineral at a favorable rate.

These moves initially set off the uranium boom that put Moab on the map. Prospectors flocked to the area, and Steen’s famous find a year later further fueled the fever. The rush of prospectors was followed by a period of wild speculation on the stock market. Historian Richard Firmage, in A History of Grand County, wrote,

“The uranium penny stock market was born in the early 1950s and soon became a major phenomenon in itself … the scramble for wealth created by the boom was coupled with the low price of stock shares … and the inexperience of many stock dealers and brokers to create a most unstable marketplace.”

In May of 1954, the penny stock trade reached a frenzied peak, with over seven million shares traded in just one day.

The population of Moab quadrupled in just a few years, and the small town struggled to keep up. Moabites who lived during that time remember drastic changes.

Pete Byrd was Steen’s roommate in college in 1939, and moved to the town in 1953. In a 1997 issue of Canyon Legacy, he recalls Moab in 1953 as a town of just a couple hundred homes made of “rocks, sticks or mud,” with “horses, cows, chickens and out-houses on every block.” He describes the town’s water and sewer systems as inadequate, Moab’s homes lagging in modernization, and Moab’s economy sluggish.

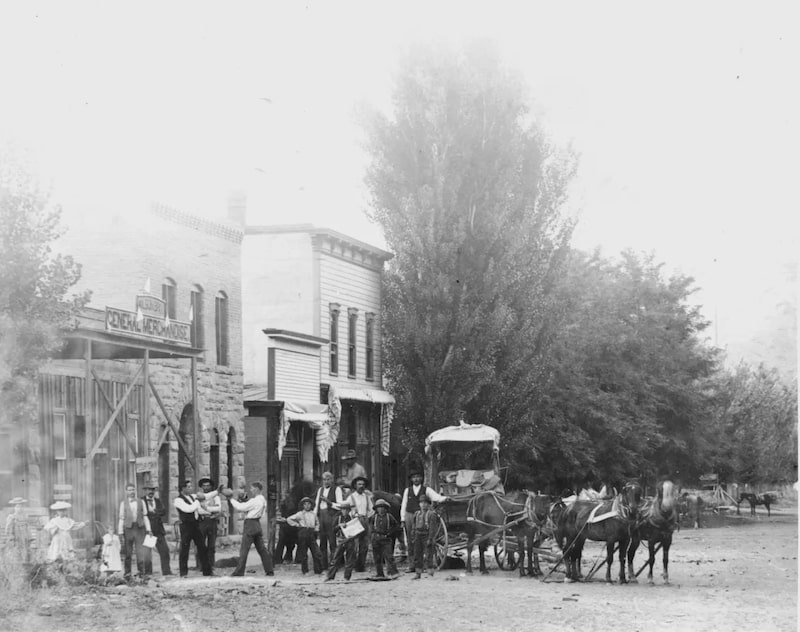

Others remember the pre-boom times with fondness. Bill Meador grew up in Moab. In a speech to the attendees at the 1998 annual museum dinner, transcribed and included in an issue of Canyon Legacy, he described the Moab of his childhood as a quiet, free place where community members took care of each other, fulfilled their own needs, and solved their own problems.

Main Street was one block long, and neighborhood kids organized activities to occupy the long summer days. In winter, they ice skated in the wetlands, hunted various small game, and the stores closed for high school football games. Mines were small and family-operated — until the famous Charlie Steen discovery.

“In 1952, Mr. Charles Steen discovered his Mi Vida mine and Moab was never again the small little Utah outpost I have been speaking about this evening,” Meador said.

Orchards made way for trailer parks, newcomers took on leadership positions, the police force expanded and taxes went up.

“Families with trailer houses came from every direction,” Byrd wrote in his recollection. Services failed to keep up with the rapid rise in population.

“During this time of extreme growth, students attended school in triple shifts, raw sewage flowed in the streets, phone lines were tied up … electrical brown-outs and black-outs were common, and water was rationed in the summers to conserve the limited supply,” wrote Moab local Kris Johnson in a Canyon Legacy article.

Author Elizabeth Pope visited the town during the boom and in 1956 published a story in McCall’s Magazine about what she saw.

“Moab, Utah is easily the richest town in the United States,” Pope wrote, doing some quick calculations to conclude that Moab had 48 times as many millionaires per capita than the nation as a whole. (In a reprint of excerpts from the story, Canyon Legacy editor Jean Atkens adds a grain of salt to this conclusion: “Keep in mind, however, that some of those referred to were ‘paper millionaires’ only,” Akens wrote in preface to the excerpts. “Their worth was counted in stock certificates and some of the mines later developed proved to be of little or no value.”)

The town’s new-found wealth didn’t manifest in ostentatious luxury.

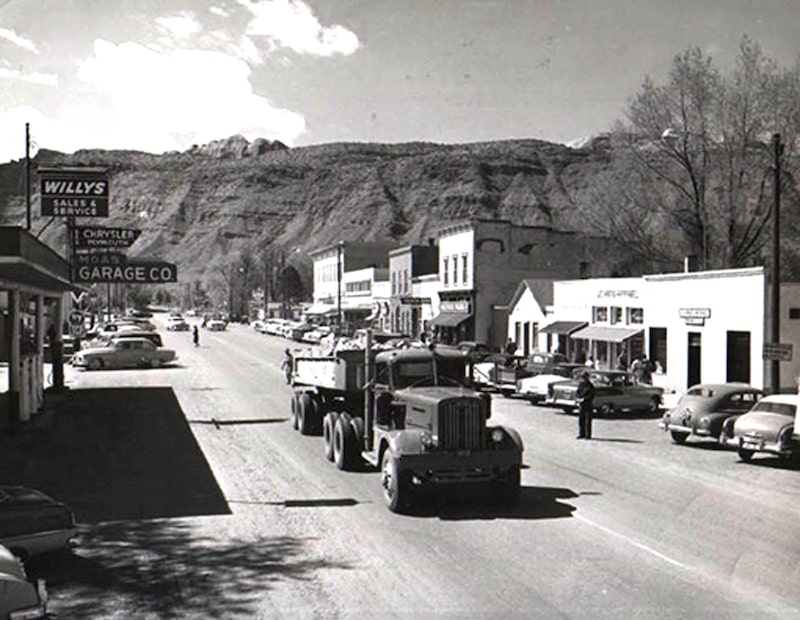

“No mink coats. No sports cars. No fancy shops. No hot night spots. No flashy neon signs,” Pope wrote of the still small and remote western town, which instead had one traffic light, a few two-story buildings, some gas stations and a plethora of trailer camps. The most obvious signs of the prevalence of the new industry were “an unbelievable assortment of jeeps, pick-up trucks, drill rigs, and huge ore-carrying trailer trucks which go roaring through town every fifteen minutes or so, en route to the local A.E.C. (Atomic Energy Commission) sampling plant.”

About a third of families lived in trailers while another third lived in tar-paper and scrap-wood shacks, Pope estimated.

Even the wealthy lived modestly, she wrote, in small cabins or modernized but medium-sized homes. The Uranium King was the exception. True to his moniker, Steen built a spacious house on a hill overlooking the valley, complete with a swimming pool and separate servant quarters.

Steen’s old house is now the Sunset Grill, where diners can still look out over subdivisions originally built to house Steen’s employees (nicknamed “Steenville”) while enjoying an upscale meal.

Even the comparative luxury of the Steen home, however, paled against the lifestyles of the wealthy in the big cities, according to Pope.

“In Greenwich, Connecticut, their home would scarcely be noticeable,” she wrote. “In Palm Springs, their standard of living would seem restrained.”

While Steen’s Moab home may have been modest compared to residences of the wealthy in more ostentatious cities, he didn’t skimp on a ranch he had built in the early 1960 in Nevada. The 17,681 square-foot home was on the market in May of this year for $16 million.

Steen was known for his generosity: he hosted annual town parties and donated land and money to civic causes.

Since it was clear to Pope that most Moabites weren’t spending money on their homes or clothes, she looked into what they were buying. Many people owned lots of vehicles, including private airplanes, which, according to Pope, became a casual mode of transportation for many of Moab’s wealthy. People also invested in securities, and bought and sold businesses and real estate.

“Land which used to cost $500 an acre now costs $3,000 to $5,000,” Pope reported.

Pope sketched the town near the height of the boom. In the years immediately following, increased regulation and consolidation of the uranium industry calmed the speculative trading and mining fever. The AEC agreed to continue buying uranium from Steen’s mill until at least 1966. After that year, uranium producers shifted focus to buyers in the private industry, who were developing uranium for nuclear power.

The uranium industry quieted down, but it didn’t go completely “bust.” It remained a significant but dwindling part of the local economy through the 1960s, and has fluctuated since then without ever completely disappearing. Other resources, such as potash and oil and gas, became more important drivers of the economy in the 1970s, but eventually, these too faded, and tourism replaced them as the prevalent local industry.

While uranium played a part in Moab’s history well before and after the famous boom, the fever-pitch of the 1950s left its mark on the town.

“The county irrevocably changed from the sleepy rural mining and ranching region of earlier years,” Firmage wrote, describing the end of the 1950s decade. “It was now both more populous and more prosperous, although a note of uncertainty was faintly audible as the uranium-based economy entered the new decade.”

RELATED CONTENT

The Evolution of Main Street in Moab, Utah

Exploring Ghost Towns Royal & Cisco near Moab, Utah

Moab’s Old Uranium Roads – Perfect Mountain Biking Trails

Gentrification of Moab — Will Growing Pains Make or Break Moab?

Moab’s Identity Crisis: Will Moab Become a Town for Tourists, Locals, or NIMBYS?

SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM AND SUBSCRIBE TO PRINT MAGAZINE

Subscribe to Utah Stories weekly newsletter and get our stories directly to your inbox