Moab residents all say they want to see the town become less dependent on tourism with a more viable year-round local economy. But lip service and meaningful change are two different things.

Some meaningful change is underway: Utah State University is expanding its campus. The airport is now servicing planes that carry fifty passengers; funding for a bypass road and a bridge has passed the Utah State Legislature. But construction for residential housing is lagging far behind hotel construction. The struggle for the town’s identity comes down to priorities -will Moab be a town for mostly tourists? Locals? Or NIMBYs (Not In My Backyard)?

While Moab’s city leaders are green-lighting more hotels they are only allowing a few concessions for higher-density residential housing. Most concessions are going to luxury townhome builders such as Rim Village and Entrada, which appeal to second-home owners. Higher density for condominiums would allow for more much-needed affordable housing. The federal government recognizes this problem. Under the Department of Urban Housing, they offer grants for cities who accommodate “inclusionary zoning.” Passed in 2018 by Congress, The Housing Opportunity, Mobility and Equality Act was designed to allow cities to zone for more density. The U.S. Department of Housing studies clearly demonstrates that opportunities for low-income residents increase with an increase in housing supply. The program offers cities community development block grants to help alleviate infrastructure costs.

Leaders have their reasons for not changing zoning. Higher density will require an expanded and updated sewer and water systems along with greater infrastructure to accommodate traffic. All of this will cause a greater impact on the environment and the parks, which could have a negative impact on tourism.

Tony Ramirez is in his fourteenth year as owner of the Fiesta Mexicana Restaurant. Fiesta is one of the few restaurants that remain open year round. “I’m keeping my doors open for the locals and my staff.” Ramirez recognizes that local residents sustain his business and year-round employment helps him to maintain his loyal staff. He says he strongly supports all measures the city can take to make Moab function better year-round including measures to build more affordable housing.

Neighboring San Juan County, just 15 miles to the south of Moab, permits what Moab will not: high-density housing and new construction. It allows homeowners to have accessory dwelling units that are nightly rentals. Walmart owns land in San Juan County and will eventually open. The ShopKo will close in May in Moab, so if Walmart opens, the sales tax revenue will benefit unincorporated San Juan County rather than the City of Moab.

Growth and development are migrating south, according to the Moab Sun News. Former Mayor David Sakrison is calling to annex land from San Juan County and help unify and increase the size of the City of Moab. Perhaps this area could accommodate big-box stores and allow for looser zoning laws, thus providing the affordable housing options to sustain a year-round economy. Currently, this area is the largest “city” in San Juan County and it’s called Moab South. The area is planning for 6,000 new residents there and they have obtained the grants for sewer and water infrastructure and building is underway. This would be more residents than currently reside in the City of Moab. This would create a clear delineation and division between the two areas.

If Moab were unified, one big advantage would be a unified tax base. This would greatly enhance the ability of the entire area to build a master plan. If Grand County and San Juan County end up dividing populations and priorities this will certainly not create the most optimal result for the area residents or the tax base.

Castle Valley

Castle Valley— fourteen miles east of Moab, is a vast expansive drainage framed by red rock cliffs and Castleton Rock. Homes here reside on 5-acre plots all with individual septic systems. Homeowners are also required to dig their own water well. Each homeowner must live like a homesteading pioneer, minus the freedom. Nightly rentals are strictly prohibited. There is also a ban on accessory dwelling rental units. Even a general store has been prohibited. The entire extent of commercial activity is one bed and breakfast, and they don’t sell milk or eggs. Over 300 people live here and those governing it say leave this place alone, so it remains a valley locked in the past.

Beside some pioneer structures, there is a lone cottonwood that must be ten feet in diameter. There is an abundance of empty lots, some of the residents who had the false hope of making a living there are now selling.

Talking to residents I find they are all are for local sustainability, but local leadership has made clear: Not In My Back Yard. Those who control the area don’t want commerce, personal property freedom or growth. They want to control the area’s beauty by limiting property rights. It is poetically pristine. This year the abundant spring snowmelt has carpeted the vast plane in spring grasses and tiny purple desert flowers. I’m told Terry Tempest Williams has property here. Perhaps it should remain the way it is. But if the goal is preservation, why five-acre plots? Why not small lots and a giant shared wildlife preserve? Deer fences are common here and wildlife travels around the hodgepodge of fencing.

A few years ago I spoke to some rock climbers who would love to set roots in Moab. Hardcore rock climbers often support their lifestyle with odd jobs: carpentry, construction, and tour guiding. Some live out of vehicles such as vans and travel vast distances to experience all sorts of pitches, types of rock and terrain. Many climbers would love to live in Moab, but due to zoning laws, they can’t set roots in Castle Valley but are forced to live in places such as Spanish Valley or San Juan County near highway 191 and buzzing power line.

Climbers on Affordable Housing in Moab

Climbers live to fully experience nature. Their greatest experiences are found hugging rocks and wedging their limbs inside of cracks seeking purchase and tension from the effects of gravity.

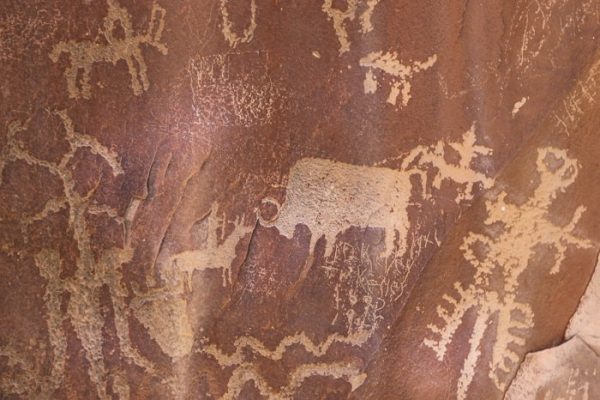

The gravity of life is the last thing on the minds of the rock climbers I find off Newspaper Rock road. It’s a road in a desolate no-man’s-land between Moab and Blanding. This is a famous rock climbers stretch I’ve heard about for years.

I approach Andrew Fernitz as he is belaying his partner. He has the glow of someone who has found his purpose in life via exploring and adventuring. He and his girlfriend skied the La Sal mountains yesterday, hiking up 2,500 feet while viewing the expanse between Moab and Aspen (where he originates). Today they are climbing four pitches in the Navajo Sandstone. They are educators in Aspen, teaching youth in the fine art of skiing. I mention to Andrew I’m writing about affordable housing.

He doesn’t have an issue with the rich elite controlling zoning. He utilizes employee housing in Snowmass Village. His solution, “If you don’t like it you can always go someplace else.” When I lament the growing crowds and gridlock in Moab, he shows a similar optimism. “We passed through there, but as you can see there is plenty of space around here…You can always find affordable housing if you don’t mind traveling a ways away from where it’s expensive.” He has been camping out of his truck. He says he loves the connection he feels sleeping outside.

A fair point, NIBYism doesn’t exist if you simply find places without backyards. I talk to more climbers. Most of these young people originate from towns in Colorado. Andres Esparaza is belaying his fiancee Kira Taylor as she ascends a meandering crack that undulates between two and six inches wide. They are soon-to-be first-time homebuyers. They are buying a place in Mancos, near Durango. It’s now upwards of half a million for a starter home in Durango. So they had to find cheaper housing away from where they work and play in Durango.

Kira tells me she worked in the affordable housing department in Jackson Hole. She said Jackson Hole’s solution for affordable housing was to shuttle many workers from Idaho. Affordable housing became non-existent there. Jackson Hole is known for its vast expanses of open space leading to the Tetons. The city didn’t allow for high-density anywhere. She says Jackson became a model for other cities facing the same problem.

Jared Veitch lives and works in Boulder, Colorado. He says a two-bedroom condo in Boulder sells in the high seven hundreds. Boulder has become one of the most sought after areas in the Western U.S. Regular-size homes sell for around $2 million in Boulder. He works in tech, so he can afford the affluent area. He tells me a long-time Boulder resident disparaging the cost of housing told him he was the cause of the high housing costs. Jared then told the man, “I want to work and live in a place where I have easy access to mountains, nature, and recreation…So do you, so what makes me any different from you?”

Those who work in tech and those who have high-paying jobs can afford to live close to nature. Others resort to living out of vans, seeking employee housing or taking long shuttles to service the rich. Still, this is a care that is far from the minds of these twenty-something climbers.

They offer me IPA and chocolate. Then Jared offers me his harness to try a climb. The more I talk to climbers the more I’ve come to appreciate their lifestyle and passion. They aren’t especially politically active. They don’t complain. Kira’s dog Pasque is sweetly barking at her when she climbs too high. It’s a nice spring day in the sun with people who are by-in-large carefree. I decide I better head back.

The town has a bottleneck of traffic heading both in and out for the spring break weekend. I stop at the local watering hole and happen to meet two men who are sipping beers after a long day out in their 4×4 vehicles. Tim Kurnos and Greg Ernst both moved to Aspen from New Jersey around twelve years ago. They have been around the government-imposed affordable housing regulations since they first moved to town. They explain to me the extent to which Aspen goes to try to both keep housing affordable and fair. They explain the restrictions applied to those receiving affordable housing to prevent abuse. To my ears, it sounds like socialism.

Anybody in Aspen who is lucky enough to receive affordable housing has a “deed restriction.” The appreciation of the home’s value is controlled not by the market but by the deed of the home. A maximum of three percent appreciation per year is allowed by Aspen’s government officials. If capital improvements are made to the home, they place a cap of an additional ten percent on the home’s value. This value then lags far behind the actual fair market value of the home.

Ernst tells me he won the lottery six years ago and was able to buy a two-bedroom condo with a deed restriction. He says normally two-bedroom condos are reserved for families, but he was able to purchase it because it was in extremely poor condition. Ernst says that despite all of the government controls, it is not unusual for cash paid under the table when lotteries for homes are won. He adds, “Aspen has 50 billionaires with homes within a five-mile radius. You have to do something special about that otherwise there is nobody who could afford to live anywhere near the town.”

Ernst works for the Aspen Times and he says affordability and exclusivity are an ongoing issue of contention. But he believes that despite measures such as restrictions on new businesses being required to build employee housing if they wish to do business in Aspen, it’s extremely difficult to get lucky enough to live there and purchase anything. “A starter home is around $2,000 per square foot. This equates to around $4 million for a 2,000 square foot home.”

Despite this, he says the divide between the rich homeowners who have millions of dollars of equity in their homes and those like him, who live in a price-controlled government lottery system does not create a clear class distinction. “Everyone there is really cool. We still have the hippy element and the local community.” Every year he says he has Thanksgiving dinner with some folks who have dozens of homes in the most luxurious and sought-after destinations.

Will Moab one day be like Aspen? Not likely any time soon. But will Moab need to resort to building employee housing in a neighboring town? Very likely very soon. Is there any clear solution to finding the balance between NIMBYism, affordable housing and growing into a year-round city? As the rock climbers told me, they regret not being more politically involved. They are all working when these important votes are happening, so they don’t vote and the NIMBYs all come out en-mass and vote to preserve their property values. So the only firm conclusion I can offer is: take time to be informed and take time to vote.