If 2020 hadn’t been apocalyptic enough, Utahns looking forward to a snowy new year got drought in January — raking leaves instead of shoveling walks, skiing on artificial powder and wondering when things might resemble normal again.

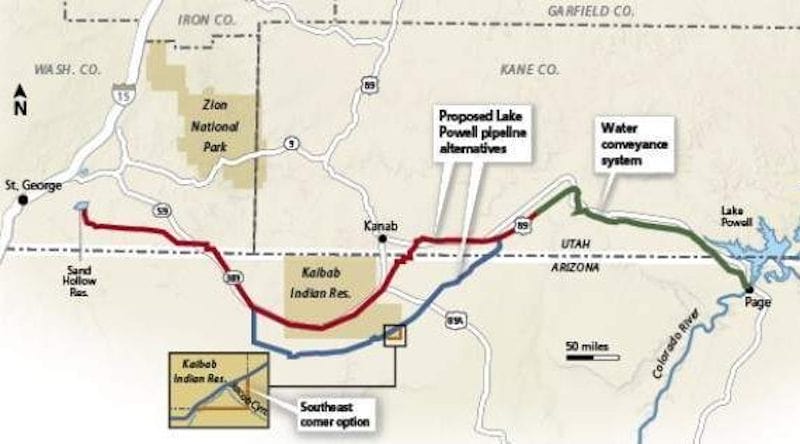

For Todd Adams, Director of The Utah Division of Water Resources, the dry climate is all the more reason water managers need to carefully consider an ‘all of the above’ approach to ensure there’s enough water to meet Utah’s ever-growing population well into the future. That includes big projects such as the Lake Powell pipeline in drought-prone southern Utah.

“We are looking 50 years out and trying to model for that,” Adams says. “Are small development projects going to help us?” Small projects and pipelines that are good enough for today won’t be as useful in years to come, because, “It’s hard to put more water through a small pipe, so to speak,” he says.

It sucks … literally and figuratively, that multi-billion dollar water projects are needed to suck up enough water for the state’s future.

But not everyone is convinced.

“What we’re seeing is a marketing campaign to convince Utahns that we’re running out of municipal water and that we need projects like the $3 billion Bear River pipeline and what we believe is a $3 billion Lake Powell pipeline,” says Zach Frankel, executive director of The Utah Rivers Council. We’re seeing hype, nonsense and misinformation presented as fact,” he says.

Sprawl vs. Green Acres

While many Utahns lament new development projects devouring old open spaces such as fields and farmlands, what is often overlooked are the water tradeoffs. The water consumption by a new home, parking lot or business is significantly less than for farmland. Despite the feeling that the state is being swallowed up by ‘burbs and big box stores, 80 percent of land in the state is actually farmland.

“That means 2.7 million Utahns are only using one or two out of every 10 gallons of water used in the state on an annual basis,” Frankel says.

As farmers sell their land to developers, it steadily frees up more water in the state.

“What happens is we are slowly converting our farm water to municipal use,” Frankel says. “But that gets left out of the conversation by the marketers of this ‘running-out-of-water’ fiasco.” Big water projects would benefit water districts more than anyone else, Frankel says, and he worries that their voice in the debate is disproportionately loud.

“If we didn’t grow hay we would have enough to support a population much larger than we have right now,” says Gabriel Lozada, an economics professor and member of the University of Utah Water Center. “More than twice the current population.”

He says if the state is weighing a big-ticket item, it might be more effective to simply pay farmers not to farm.

“All the farmers together generate less than two percent of the gross state product,” Lozada says. “If we had to, we could pay Utah’s farmers two percent of gross state product for all of their water. That means we could multiply by five the amount of water Utah cities had.”

It is a bold proposal, and one he admits might adversely affect rural communities that center around farms. But he notes these communities are already suffering with farms selling out to developers. The point is that many farm communities might become ghost towns as has happened in other cities such as Phoenix. The difference would be Utah policymakers could do something for farmers now before their way of life disappears by a natural economic withering. It could also help not only farmers but cities as well.

“It’s a lot of money, but frankly, Utah cities generate a whole lot of economic activity,” Lozada says.

Pipeline Paradox

Lozada also did research on both the Lake Powell Pipeline and the Bear River pipeline proposals. He found problems with the payment of both projects. The Lake Powell Pipeline would require water rate increases for local users to pay off the expensive bonds. But the rate increase would also make people use less water. By using less water, they can’t pay off the bonds.

Lozada joined 21 other economics professors from across the state in writing a letter to Governor Gary Herbert in 2015 warning about this dilemma, noting that water rates alone in Washington County would have to increase by 576 percent to 678 percent to pay off the pipeline debt.

“In our analysis, demand decreased so much that the [Lake Powell Pipeline] water would go unused — which the Division of Water Resources did not consider,” the letter stated.

He found a similar problem with the Bear River project, with smaller northern Utah communities not likely being able to foot the increased water bill rate for the project and being forced to drop out of the project.

He notes that with the Lake Powell Pipeline, the residents there already have the potential to conserve more water because they currently pay so little for it. DWR director Adams also says that where conservation efforts have gained traction, it’s helped negate the need for big water projects.

DWR director Adams recalls that policymakers once thought the Bear River pipeline would need to be running by 2015, but thanks to aggressive conservation efforts, that turned out to be unnecessary.

Adams says that big projects may be delayed, but feels they will be needed eventually. He also says conservation efforts are still a big part of the equation and the state has set a goal of reducing aggregated water use in the state by 16 percent from previous measurements by 2030.

“But conservation costs money in order to run media campaigns,” Adams says. Beyond educational campaigns, the division is hoping for more funds from the legislature for rebates for smart water control devices.

The division is also excited about another innovation passed in the 2020 legislative session — a law allowing for the creation of “Water Banks.” These would allow farmers, irrigation companies and other parties to form a bank that would allow them to lease water to other parties for a fee without giving up their rights to the water. This could create a versatile type of water market, as opposed to the current “use it or lose it” system.

“This creates a lot of additional flexibility,” says Candice Hasenyager, a deputy director with the Division of Water Resources.

For others, like Frankel, conservation is key above all other things. He also says that it would be the most effective tool if it weren’t for a quirk in the way municipalities, especially in southern Utah, hide water costs by including them in property taxes. In essence, these property taxes prop up a commodity market.

Stepping back for a minute, the idea seems unbelievable to Frankel. Taxes subsidizing water districts, to stand up an industry that seems unwilling to survive solely on the raw capitalism of supply and demand? In a free market system? In Utah?

“It’s not the Republican Utah we’ve been led to believe!” Frankel says with a laugh.

Subscribe to Utah Stories weekly newsletter and get our stories directly to your inbox