One of the many remote, seldom traveled, yet now famous places near Moab, Utah is Bluejohn Canyon. If the place name doesn’t sound familiar, perhaps the movie 127 Hours starring James Franco does. Or perhaps the name Aron Ralston rings a bell. He saved his life by amputating his own arm after it became pinned under an errant chock stone.

Traveling throughout Utah and writing about some of the most remote regions has brought me to the area known as the “Maze District,” a name fit for a Hollywood film. The district is a labyrinth of slot canyons, and a lone decomposing jack rabbit in a narrow slot canyon signals a clear warning. Without knowing where the canyons go or how to get in and then get out, a person could very likely end up lost or dead. This area is part of Robber’s Roost, where no outlaw was ever caught, because the robbers could always evade the law.

Unlike Ralson, I’m not alone. I came with NAVTEC Expeditions, a touring company whose guides, Brian Martinez and Dave Pitzer, know this area inside and out. They also possess a satellite phone in case anything goes wrong. Approaching the canyon, we pass a series of sand dunes. White cumulus clouds stand out in the eastern sky. “Those are all going to dry up after they pass the Henries,” Brian tells us. I take his word for it.

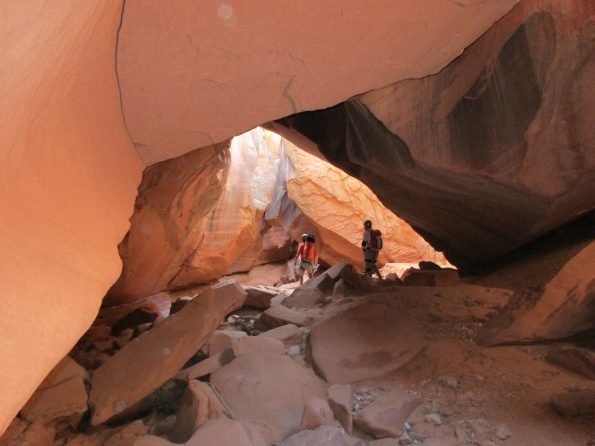

In desert sand we trek into a shallow wash, and after just two miles we reach “Ralston’s Rock” where Aron’s arm was pinned. The polished rocks in this area show the effects of the regular beatings the rocks, boulders and massive cottonwoods take every time flash floods send millions of gallons of water through these narrow crevasses. We descend further under cottonwood trunks wedged between the canyon walls. Atop the trunks are boulders similar to the one that pinned Ralston. Dirt, tumbleweeds, sticks and rocks are all part of the canyon’s debris.

The canyon walls are alluring, smooth and sensuous, yet devoid of living organisms. Millions of years have wrestled, pounded and condemned all attempts at life. No plants grow in the cracks; there are no amphibians or mammals. Not even insects, yet the awesome slot draws us in.

The canyon walls are alluring, smooth and sensuous, yet devoid of living organisms. Millions of years have wrestled, pounded and condemned all attempts at life. No plants grow in the cracks; there are no amphibians or mammals. Not even insects, yet the awesome slot draws us in.

We rappel a series of increasingly tall cliffs—15 feet, no biggie, but the 30-foot rappel elicits a bit of anxiety. At the end of the canyon is a sheer cliff with a 100-foot drop. With Brian’s confidence and know-how, once I’m over the ledge it’s a smooth glide down to the base of the canyon floor. Ravens swoop overhead hoping there might be a failure in our decent, and once again there are desert cacti and Mormon Tea. We have returned to signs of life on earth.

In 127 Hours, this was the point where the star dives into a pool at the end of the canyon, “After a flash flood this would be filled with water, but the water is red.” Brian says that scene was filmed in Leprechaun Canyon.

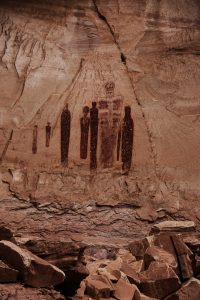

He points out several other movie discrepancies, but as we reach our next destination, Horseshoe Canyon, it becomes clear that this area tells a much more important story than the one Hollywood has portrayed. We approach the Grand Gallery, where, over 5,700 years ago, alien life forms have painted their likenesses in the rock. These floating creatures without arms or legs stand 10 feet tall. They are spooky, and they surround a man painted white and glowing. Scientists might have a different interpretation, but I figure mine is just as good as anyone’s and this is what I see—this Grand Gallery does have some human forms, but the floating, eerie creatures depicted on these walls are some of the best examples of pictographs anywhere in the world, and, like the Egyptian pyramids made over 5,000 years ago, these paintings possess an other-worldly distinction.

He points out several other movie discrepancies, but as we reach our next destination, Horseshoe Canyon, it becomes clear that this area tells a much more important story than the one Hollywood has portrayed. We approach the Grand Gallery, where, over 5,700 years ago, alien life forms have painted their likenesses in the rock. These floating creatures without arms or legs stand 10 feet tall. They are spooky, and they surround a man painted white and glowing. Scientists might have a different interpretation, but I figure mine is just as good as anyone’s and this is what I see—this Grand Gallery does have some human forms, but the floating, eerie creatures depicted on these walls are some of the best examples of pictographs anywhere in the world, and, like the Egyptian pyramids made over 5,000 years ago, these paintings possess an other-worldly distinction.

Follow this link to view the video Richard Markosian produced of Bluejohn Canyon.