Jordan Hess holds a $24,000 violin aloft by the neck, like a popsicle. It’s not actually a $24,000 violin … yet. First the bare, white-looking wood needs to get colorized with a red oxidizing solution. After that dries, he’ll coat it with another solution to “activate it,” and then it’ll go under an ultraviolet light to turn it “hopefully old-colored,” Hess says.

“It’s like going to a salon to get a tan, except it’s wood.”

Hess is the owner of Sugarhouse Violins. As he talks, Hess never stops working. His hands are in constant movement, slathering the watery red solution generously over the violin with what looks like an ordinary paint brush from a hardware store. After the colorizing treatment it will get lacquered and delivered to the buyer who commissioned it.

Not yet 30 years old, Hess is an an up and coming maker in the field, with a backlog, generally, of anywhere from six to 35 instruments. Among his past buyers are the Los Angeles concert violinist Christian Fatu and Yefim Romanov, first assistant concertmaster of the Florida Orchestra. Much of his clientele are music conservatory students.

“I’m still at a price point where they can afford me,” says Hess, who is unfailingly modest.

Of winning a “Certificate of Tone” award from the Violin Society of America last fall, Hess attributes his accomplishment to happenstance. Some 430 violins were evaluated during the competition, which is only held every other year. More than 21 countries were represented.

“Realistically, the instruments that the judges look at right after they’ve had a break and some food score really well,” says Hess. “So I lucked out.”

The humility feels genuine. To be in demand in such a crowded market is obviously quite an accomplishment. As home to one of five major luthier schools in the country, Salt Lake City boasts at least half a dozen local shops offering custom instruments and restoration services, and the Violin Making School of America is well-known. Hess attended the school himself before leaving to take an apprenticeship with renowned luthier John Young.

“He’s just an amazing teacher. That opened a ton of doors and helped me get to a placewhere I could continue learning on my own without having someone standing there helping me out,” Hess recalls.

At that point, Hess was making about 20 to 25 instruments a year, and was able to finance opening the shop, which needed to be renovated. Being a woodworker was a helpful skill.

Working with wood has been a life-long passion for Hess, who says he started building a sailboat at the age of nine while growing up in Indiana. By age 12, he was helping a neighbor with a small wooden aircraft. At 14, he made his first, unsuccessful attempt at building a violin. Once the strings were tensioned, it basically blew up, Hess recalls. “It’s a pile of bits now.”

After his father took Hess to a violin shop for advice, they suggested he hang around and learn. It just snowballed from there.

In order to keep the revenue flowing, Hess has turned much of his effort into restoring, where final payment is guaranteed. Sometimes customers will commission a piece and then end up not buying it. With restoration work, clients can be counted on to pay to get their instrument back, and as the business has grown, he has employees and obligations.

He just hired his first-full time restorer. Another maker, Hannah Fenn, also works out of the shop. Fenn, herself a seventh generation maker of German heritage, apprenticed with Hess for two years. The shop also has two other part-time employees.

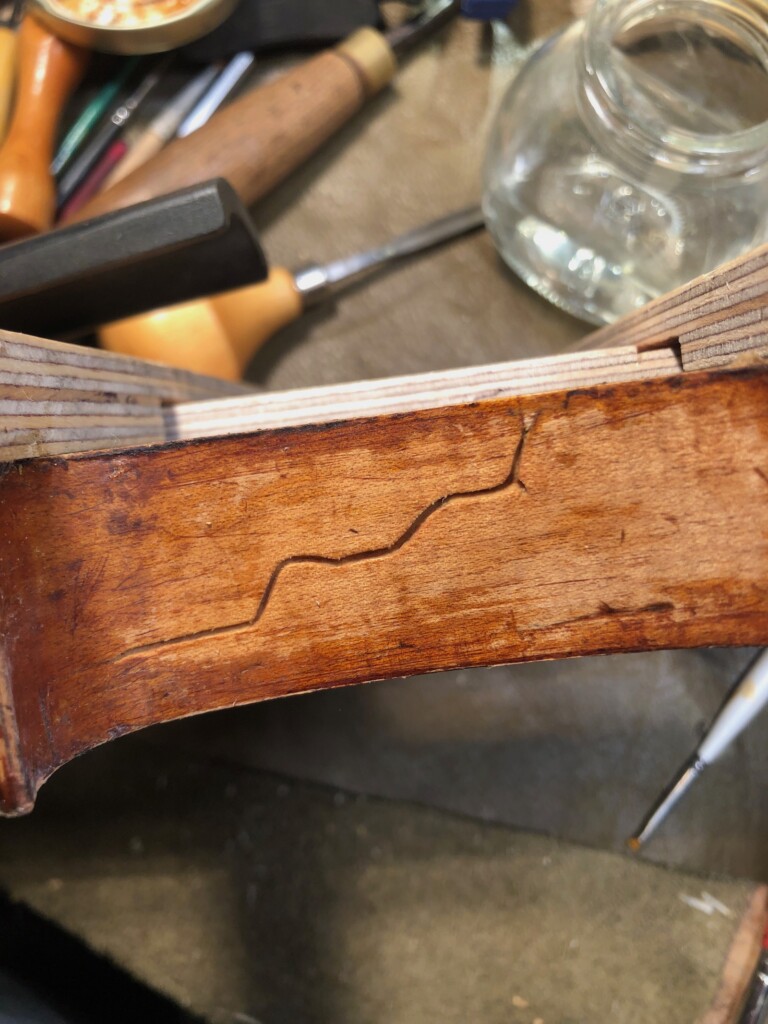

Hess switches his attention to an 18th century instrument he is restoring. The violin, which was made by Nicolò Gagliano, was eaten by worms about 100 to 150 years ago, according to Hess. Now, the previous worm-fill repairs are starting to fall out and Hess is examining the violin under a microscope. A replacement piece of wood will have to be carved in the exact shape of the hole and fitted.

A single hole can take days to repair. So far, Hess and his team have put in about 1,000 hours into this one violin. Hess wouldn’t say what the violin is valued at, but in March of this year London-based auction house Ingles & Hayday reportedly sold another Nicolò Gagliano violin for $221,556.