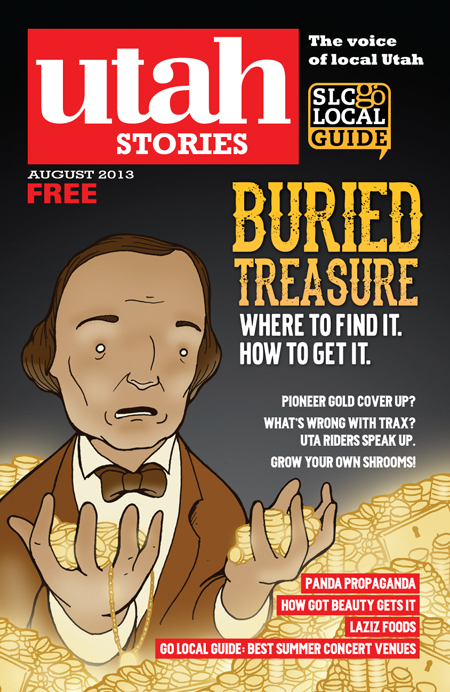

Old-timers say “for every ounce of mined gold, gallons of blood have been spilt.” The most sensational Utah tale concerns the lost Rhoades Mine.

Thomas Rhoades was commissioned as Brigham Young’s representative to the Ute Chief Wakara. Chief Wakara allegedly accompanied Rhoades the location of a fabulously rich mine, the wealth of which was to be used only to benefit the LDS church. Historians now discredit the story that the Ute Indians gave gold to the Mormon pioneers, and also allowed Thomas Rhoades, followed by his son Caleb, to mine gold from the Uintas for several decades.

Gale Rhoades spent most of his life following in the footsteps of his great-grandfather Thomas Rhoades, attempting to find lost treasure. He made a living establishing illegal prospecting corporations using a gold nugget he claimed to have originated from the Uintas. Speculators would finance his attempts to find the gold based on his convincing evidence and his published book Faded Footprints: The Lost Rhoades Gold Mines & Other Hidden Treasures of the Uintas. Gale Rhoades died owing thousands of dollars to investors. Gale Rhoades was certainly a con-man exploiting his relatives.

Phony Obituary in the Deseret News: What did they have to hide?

Thomas Rhoades, however, was described in his obituary in the Deseret News in 1890 as “a mighty hunter of grizzly bears.”

In fact, Thomas Rhoades did deposit more gold for tithing than any other pioneer. Rhoades tithed so much gold he was given a house next to John Taylor, Brigham Young and Willard Richards. Where did he get around sixty pounds of gold worth $17,000? According to the church it all came from Sutter’s Mill, this is likely true. But there was much more gold coming into the Mormon Pioneer economy from undocumented sources.

The early history of Utah is incredibly incomplete. There is a growing body of evidence showing that the Aztec empire did indeed extend far beyond the Four Corners area. Parowan Gap is certainly a Fremont Indian or Aztec site. Myths, legends or facts could be unraveled with more study.

Current Utah high school textbooks begin with friars Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante visiting the area in the late 1770s. But actual records of the Utes and their interaction with the Spanish empire date back to the early 1600s. There were over two hundred and forty years of Ute-Spanish relations predating the Mormon pioneers. The mystery of the Lost Rhoades Mines persists because the history is so one-sided. Is there a Ute account of this same legend?

Ute Indians and The Lost Rhoades Mine

Chief Wakara was a highly successful leader because he learned to take advantage of the introduction of the horse. His band of Timpanogos Utes was one of the few groups of indians in Utah who were well-trained equestrians. They used horses to conduct seasonal migrations for hunting game and plundering enemies. Wakara used a single-action shooter pistol, which he carried with him at all times. Abandoning the popular wikiup shelters, Wakara and his tribe adopted the portable teepee.

“They were robbers of a higher order than those of the desert. They conducted their depredations with form, and under the color of trade and toll for passing through their country.”

John C. Fremont in 1844

Young and the other Mormon leaders also had a high opinion of Wakara. Young saw him as an intelligent man. The Utes were still reeling from the changes they had been adapting to from the past 300 years of Spanish domination.The problem Wakara suffered was that his lifestyle relied on slavery and theft. Wakara’s Utes would seasonally migrate to California—Mexican territory at the time—to steal cattle and horses from their Spanish/Mexican enemies. Wakara would also raid neighboring interior tribes such as the Paiutes and enslave their children. He would then trade his captives and animals in Santa Fe for food, ammunition, blankets, feed and supplies.

Wakara must have understood the value of gold usage in currency. If he knew about Spanish gold mines or a former Aztec mine, one would wonder why Wakara wouldn’t exploit gold for currency?

But Wakara and other Indians did not culturally acknowledge personal property rights and land ownership. They called gold “yellow rock” then “money rock.” Wakara initially gave away most of his land to Mormon pioneers as long as they would move onto the lands, graze their animals and grow crops. He wanted pioneers living there, because he knew they could put the land to good use. Wakara had a long-term vision for the land and his people. He saw the value of integrating his people and adapting his culture to the new modern ways. He also knew that these more friendly white men would likely protect the Utes from their enemies. The nearly 300 years of incomplete Utah history, found scarcely in history books, was likely similar to what was more well-documented in South America. The Spanish were ransacking the regions and tribes for wealth in any form.

Neglected Spanish Ute History

The earliest mention of the Utes was from Spanish Governor Luis de Rosas in Santa Fe who reported the capture of eighty “Utikahs.” They were forced into labor workshops. According to legend, at about the same time, many Utes were taken as slaves to work in mines (both silver and gold) in the Uintas for their Spanish captors. The former account is according to historical records. The latter is according to journals written by pioneers recounting what Chief Wakara had told Mormons about his people’s history. Wakara spoke Spanish, English and Ute.

Archaeologists need to visit and carbon date smelters which have been found in the Uintas to see if they pre-date the Mormon pioneers. No such archaeological research has been conducted. Scholarly, academic historical research is very limited on Chief Wakara. This is a shame, because the puzzle of whether or not Wakara gave gold to the early Mormon pioneers could be easily solved if research dollars were placed into answering these questions. Pioneer journals currently residing at the Church History Library and scarcely allowed to be opened by inquiring reporters, could also answer more questions. The answers are very likely available. After the initial Footprints in the Wilderness was published, the LDS Church allowed Kenneth Davies to tell his true story, using many of their archives. His manuscript is called The Forgotten Pioneer. The story revealed that there was indeed a cover-up as to who Rhoades was and the nature of his work.

Scholarship Debunking the Myth of the Lost Rhoades Mine

Davies found in his research that Rhoades was a Danite, meaning he was not to reveal that he was a Mormon working for the LDS Church. There was and possibly still is a secret society in the Mormon Church just as the Templars operate or operated in the Catholic Church. The Danites were given very special missions to gather intelligence and report directly to the Church authorities. Indeed Thomas Rhoades lived at the base of the Uintas for thirty years. All area residents with ancestry in the Kamas valley claim that both Thomas Rhoades and his son Caleb were mining in the mountains. Most residents in Roosevelt near the backside of the Uintas believe the lost Rhoades Mine stories, especially the danger involved in attempting to find the gold; they know people who have disappeared.

The backside of the Uintas is full of mystery. To access the Eastern Uintas backpackers need to begin in Whiterocks on tribal grounds. It’s the place that hikers don’t frequently visit; thousands of acres of untamed wilderness remain mostly untouched. Ashley National Forest borders tribal grounds, where hikers are informed “No trespassing.” Treasure hunters, explorers and lost gold enthusiasts have determined that east of Fort Duchesne, in Whiterocks’ Rock Creek is the place where millions of dollars of gold lies in abandoned mine shafts and caverns, left there by both the Aztec empire and Spanish explorers. Blood has likely been spilled here. In researching this story at the LDS History Library, a librarian asked me to keep an eye out for her grandpa “Buck” who went there seeking gold twenty years ago and never returned.

I was on the reservation ten years ago working on a story about Ute education. When I asked a student named Davy if he frequented the High Uinta wilderness he replied “We don’t go up there.” “We heard there is a group of Indian warriors, living in the old way— teepees, bow and arrows. They are protecting a golden temple in the rocks.” The serious manner in which this 19-year-old Ute spoke sent a chill down my spine. The “myth” that Indians are still dressed like warriors protecting a golden temple sounded like a nice opening for an Indiana Jones sequel.

Is there gold in the Uintas? Was there gold in the Uintas? Is there much more to the Ute Indians and their past relations to the Spanish? These are questions that historians and scholars should attempt to answer.

Utah Stories has written a follow up article where we speak to two area experts about the lost Rhoades mine. Read it here..