A Sugar House that never produced sugar: How initial attempts failed, but in the end produced a huge industry from which Utah would greatly benefit.

Sugar House is an area in Salt Lake City that is full of bungalow houses, parks, tree-lined streets and a community of mostly liberal, yuppie-types who drive their Subaru wagons to Whole Foods to buy overpriced organic goodies.

But the “Sugar House” name isn’t a marketing ploy to attract yuppies. The area offers a rich history dating back to one of the first Mormon Pioneer business endeavors.

Sugar House pays homage to an actual sugar factory that was ordered to be built by Brigham Young in a first attempt to produce granular sugar from sugar beets.

For the first 20 years the Mormons were in the Salt Lake Valley, sugar was a rare, expensive commodity — approximately $35.81 per pound in today’s dollars.

In Pioneer times it would have been common knowledge that Napoleon Bonaparte began the world’s first sugar beet processing in 1811. Prior to this innovation, sugar had to be extracted from sugar cane. Other sweeteners were used in the form of molasses made from beets or sorghum.

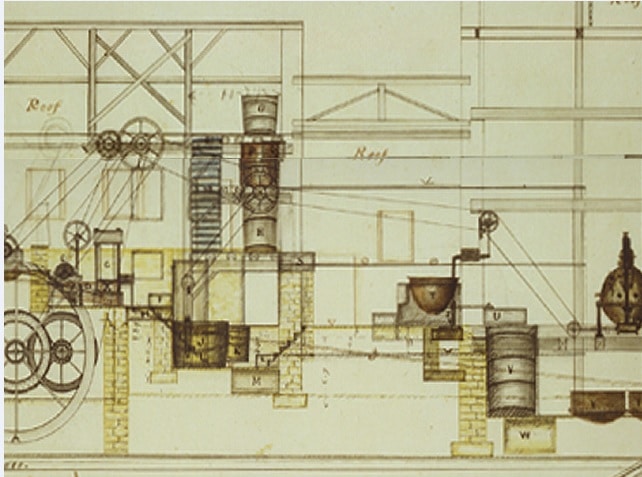

The sugar beet production process required the use of CO2, lime and bone char to remove the impurities from beet juice. The French were the first to utilize a vacuum chamber that could lower the boiling temperature of purified syrup, making it possible to crystallize syrup into granular sugar.

This was a modern marvel in the 19th Century and the industrious Mormon Pioneers saw dollar signs when they considered what a benefit it would be to produce the first sugar in the quickly-growing Western United States.

Brigham Young ordered John Taylor and Phillip DeLamore to head the Deseret Manufacturing Company (DMC), and sent them to learn sugar production in France. Taylor purchased the equipment in Liverpool and made arrangements to have it shipped across the Atlantic to New Orleans. They had to haul 10 tons of equipment, but found their wagons insufficient, so they bought a team of Santa Fe Prairie Schooners.

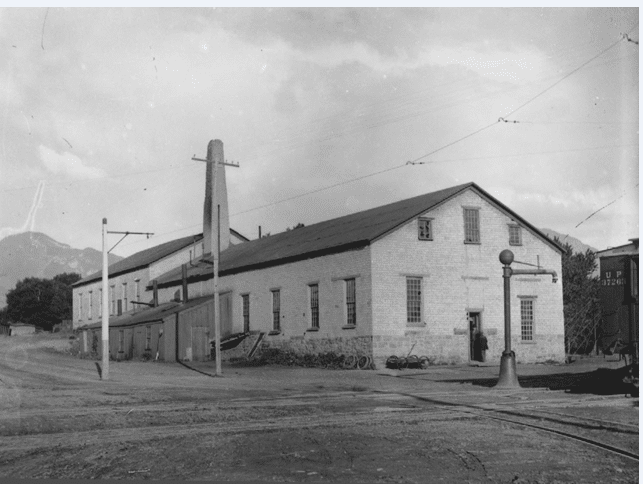

Young also ordered a building constructed that would be used to process the sugar beets. It was efficiently built — beets go in one end, sugar comes out the other. Unfortunately, turning beets into sugar proved much more complex than anyone imagined.

First, there were problems hauling the enormous equipment over the mountains. The vacuum pan, which was estimated to weigh over six tons, had to be abandoned in Logan canyon over the winter.

Once the Mormons were able to move the vacuum pan, they began working on calibrating the process.

After months, sugar still wasn’t being made, and Young removed Taylor from the job and took over operations himself. Young moved all the equipment just outside of his estate near Temple Square so he could directly supervise the process. Wilford Woodruff cheered Young on and believed strongly that if anyone could make sugar it would be the Prophet. But Young also failed.

In the end, the Mormons produced a sugar that would “take the end of your tongue off.” Brigham Young would not live to see sugar produced in Utah, but his successor, Woodruff, re-established the effort thirty years later.

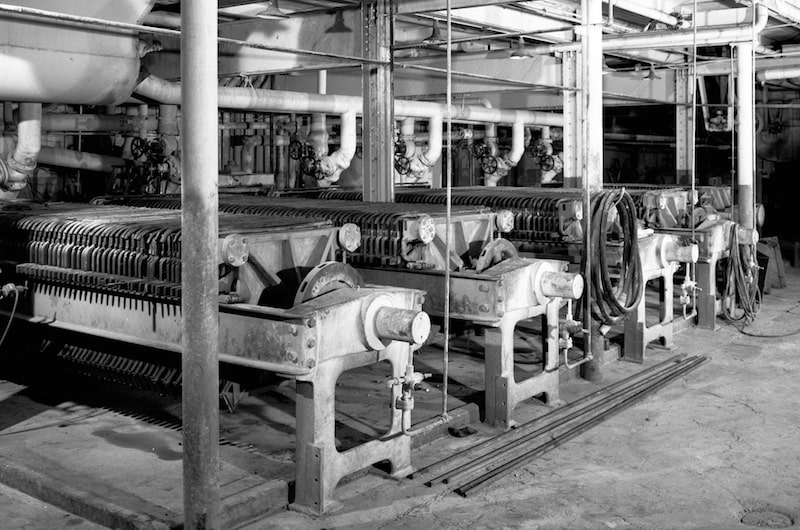

Woodruff, along with Heber C. Grant, raised $100,000 — a fortune at the time — from the wealthiest Mormon businessmen to revive the sugar business. After hiring a sugar technology specialist, they built a $400,000 factory in Lehi, Utah. Known as Utah & Idaho Sugar, the new factory was capable of processing 1000 tons of beets into sugar per day.

Later, U&I Sugar faced charges of price fixing and monopolistic practices by the U.S. Justice Department.

Over time, the LDS Church sold the majority of their interests in U&I sugar to church members. But for nearly 100 years, sugar beet farming became the perfect industry for sustaining LDS families with an abundance of children.

Read more about the Sugar Beet industry in Utah in Matthew Godfrey’s book Religion, Politics, and Sugar: The Mormon Church, the Federal Government, and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company.

A version of this story ran in Utah Stories 2009.

Subscribe to Utah Stories weekly newsletter and get our stories directly to your inbox