Doc McNeal has worked with livestock since he was a boy, sheep in particular. (All of his academic degree theses were written about sheep.) For Navajo, sheep represent the Good Life, of living in harmonious balance with the land.

Doc Mc Neal too has a deep respect for nature. He also grew up near and around Native Americans and the discrimination he witnessed profoundly impressed and upset him. Threads spun from different fibers, but yarns blend together to create a whole piece.

“When I discovered the Churro sheep and realized that they correlated with the largest Native American tribe, and then I learned how the Navajo sheep had been mistreated, I thought, ‘I need to do this.’” In 1977, when Lyle McNeal started the Navajo Sheep Project, there were an estimated 435 Churros scattered around the West. Through is “own time and own dime” efforts, there are now approximately 4,500 Churros, many of which are on the Navajo Nation.

Churro are hardy, disease and parasite-resistant, can withstand extreme climates; they are easy lambers, their meat is lean and milk nutritious. The long, outer coat of their double-coated fleece has low grease content, which allows yarn to be spun by hand. Preserving the Churro means that this versatile breed will continue to strengthen biodiversity. “Diversity is important so that we have insurance against the risk of losing plants and animals as a result of monoculture,” McNeal asserts.

It’s thanks to “Doc” McNeal’s work that Navajo Churro sheep still exist in North America.

The history of Navajo Churro sheep is tightly woven into the centuries-long tapestry of European exploration and settlement of the now-American Southwest. A dominant design element on that tapestry is Navajo people’s relationship with the Churro.

The CliffsNotes version of that story is: Spanish explorers brought churra sheep to the New World. Spanish herds were established in the Southwest in the first half of the 17th century. Navajo acquired what, by then, were called Churro sheep, quickly became skilled shepherds, and their collective flocks swelled to between 600-700,000 head. Manifest Destiny beliefs motivated strong-arm and brutal policy actions aimed at the Southwest’s Native American inhabitants.

In 1864, US government troops destroyed Navajo orchards, killed their livestock, and forced approximately 9,000 Navajo to walk 300 miles to an internment camp in New Mexico. Upon returning to their homeland after three years of imprisonment, the Navajo rebuilt their lives, to include reestablishing flocks of sheep that were a central part of their livelihood and culture. Herd sizes again grew, but in the 1930s, federal officials asserted that perceived overgrazing by the sheep in already Dust Bowl conditions would cause detrimental silting in the machinery of the government’s Hoover Dam project. The government then implemented a euphemistically-named livestock reduction program, the result of which was the slaughter of an estimated 400-600,000 of the Navajos’ goats and sheep.

Doc McNeal calls this eradication the “Navajo Holocaust” because as much as the sheep were a monetary asset, the Navajo also consider the sheep sacred members of their peoples’ family. Scattered in remote canyons on the Navajo Nation, however, were Churro survivors, but when Dr. McNeal was teaching in the Animal Science Department at Cal Poly Tech in the early 1970s, he was unaware that any of the breed still existed.

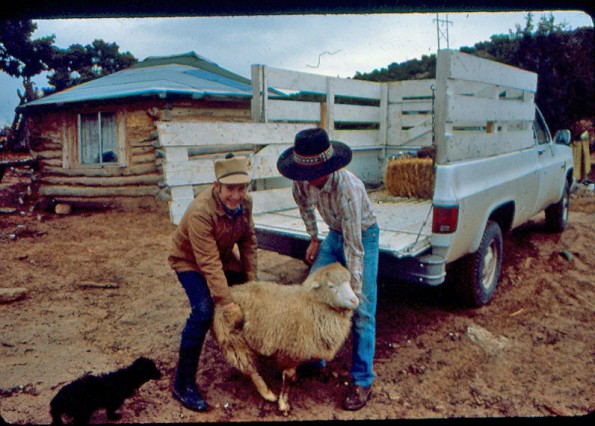

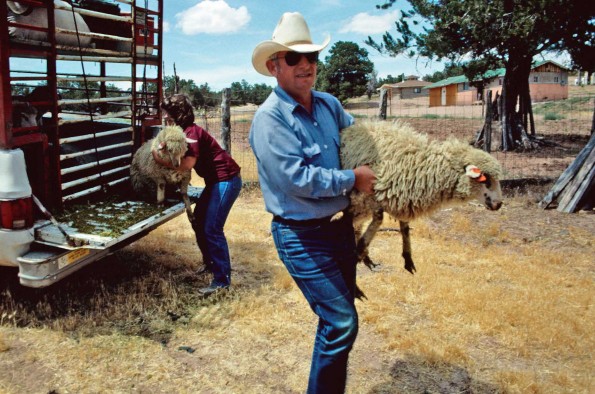

His efforts, however, extend beyond genetic conservation and encompass saving a traditional way of life for a marginalized people. “In 1982, when we started returning sheep to the Navajo,” McNeal says, “elders would come up to the truck and look at the sheep while we were getting gas and start telling stories. They’d have tears in their eyes.”

Returning the Churro to the Navajo is a project which honors a solemn suggestion McNeal’s grandfather made to him when Lyle was an adolescent. When trapping in Canada, his grandfather was attacked by a wolverine. He would have died had not the native Athabascans taken him in and nursed him back to health. Doc McNeal remembers his grandfather saying, “Lyle, we need to do something good to the native people. This,” McNeal says, “is going to be my payback on Mother Earth.”

http://navajosheepproject.com/