The Penelope Program

Until he was six-years-old, Tyler Teuscher was a normal, healthy little boy with hearing problems. But then things changed.

The first things his family noticed were some balance issues. He started to fall over a lot and they noticed his gait changed when he ran.

Six months later, his father, August Teuscher , explained, “His eyes started to look off to the right or left. The doctors discovered atrophy of his optic nerve. He started losing his vision and his cochlear implant stopped working. At 10 he stopped walking.”

The Teuscher family traveled the country with Tyler looking for a diagnosis and a cure while his symptoms kept worsening. And although his test results came back fine, they were told the nature of his disease was terminal and they had all but decided to stop looking for answers.

Then they heard of the Penelope Program for rare and undiagnosed diseases at the University of Utah. They met with Dr. Lorenzo Botto and the team there. The process involved taking a DNA sample from Tyler and other members of the family for comparison in DNA sequencing. With the help of computer engineers and a pediatric team, an answer and help were finally discovered.

At last, they had a name for what was happening to Tyler—CMTX5—a very rare mutation that could be treated with a nutritional supplement, SAM-E amino acid, available at most health food stores to improve his symptoms. It was not a cure, but would greatly improve his quality of life.

“The first thing that got better was that Tyler didn’t need as much rest. He started spending time outside instead of in bed, even pulling himself up onto the trampoline. He started crawling faster, knocking down anyone in his path. He had new unlimited energy. After surgery and using a gait trainer and wearing braces he was even able to run, walk, and ride a bike. The supplement is not a cure and Tyler will still decline, but he is so much better off than ever before—100 times more,” says August.

After years of frustration and searching, the Penelope Program offered not only a diagnosis but hope for Tyler.

As August says, “They took all of our sadness and turned it into something beautiful.”

Gabor T. Marth, DSc—Co-director of the USTAR Center for Genetic Discovery

Part of the Penelope Program involves the USTAR Center for Genetic Discovery.

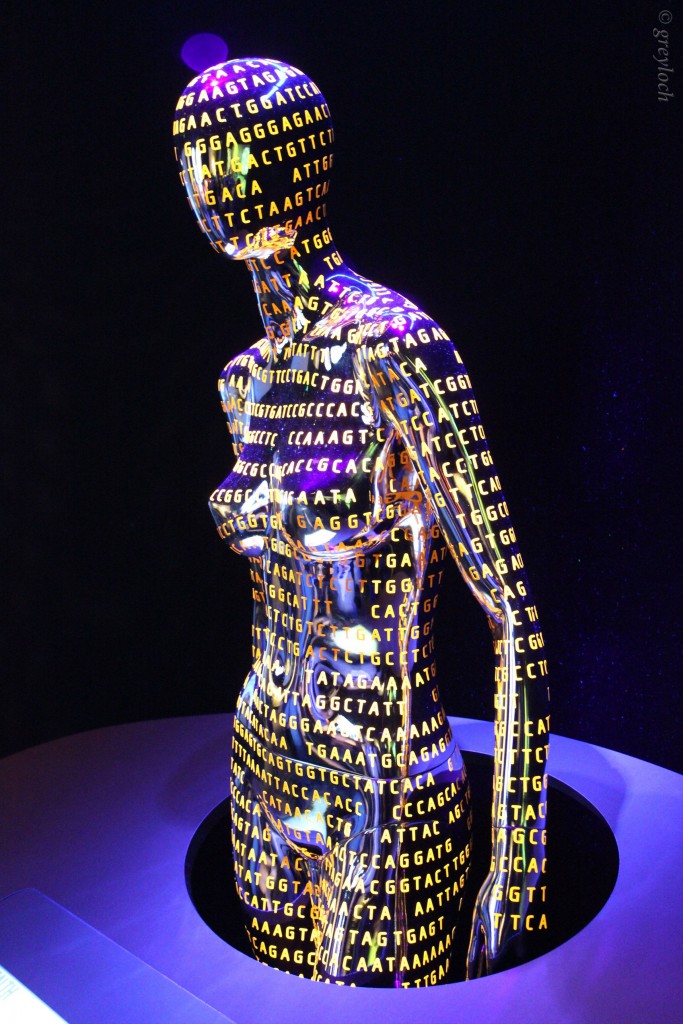

According to Gabor T. Marth DSc, “We look at the genes and genome of patients primarily to try to understand why they are sick, what causes their disease, and if possible, find a cure.”

Marth and his team study rare diseases and cancer to try and understand how they occur through genomic sequencing. For example, “We look for genes that are active in a particular tumor at a particular time, and compare that to “normal” genes. This can lead to a diagnosis and understanding. It can also help doctors deliver personalized oncology-specific drugs that will work best for that patient,” Marth says.

They work primarily through computational tools using computers and algorithms to analyze an extremely large data set of genomes. The process can take anywhere from a few days to a few minutes when suddenly, the results are “entirely obvious,” while other cases can take many years, or a diagnosis may never be found.

Part of the Penelope Program involves the diagnosis of rare diseases by identifying mutations or genetic variations.

Marth explains that “Until there was genetic diagnosis some diseases couldn’t be diagnosed. Patients with a rare disease, typically pediatric, develop symptoms, sometimes just after birth, that defy understanding.” But through the process of sequencing, it can be determined if a DNA mutation is the cause of the disease in well over half of the cases the department sees.

And though Marth says it is easier to find the cause than a cure, “Sometimes you can tailor the treatment to the cause.”

Such was the outcome in Tyler’s case. And though there is not always a cure for the diseases they identify, just knowing the cause can help guide research for a future cure.

“It is often our experience that it is important for parents and family to understand and understanding itself is important,” Marth explains. “The disease is no longer in the domain of the unknown, but we can understand what is causing it. Knowledge is very powerful.”

Dr. Lorenzo Botto

Lorenzo Botto, MD, originally from Italy, is a professor of Pediatrics at the University of Utah School of Medicine. He trained in Europe and the United States in Pediatrics, Pediatric Cardiology, and Medical Genetics, with further subspecialty training in Biochemical Genetics.

Since 2016, Dr. Botto has been leading the Penelope Program at the University of Utah Health for children with undiagnosed diseases.

This multidisciplinary team of clinicians and researchers examine and assess patients by searching their DNA for variants that lead to disease. They utilize the expertise of ARUP Laboratories and the USTAR Center for Genetic Discover also at the University of Utah, known for developing innovative genomic analysis tools.

“I liked pediatrics, and when it was time to specialize, medical genetics was becoming the cutting edge of science. It was a chance to tackle some difficult problems that affect families and was a nice combination of science and medicine,” Dr. Botto says.

He came to Utah because of our commitment to families and to make progress and improve the lives of children. “The combination of high-end science with commitment to families was very attractive and drew me to this particular program.”

The Penelope Program brings together experts in a number of fields including Bioinformatician, molecular geneticists, clinical specialists in neurology, cardiology, and gastroenterology. All specialists work together as a team and pool their “remarkable cognitive expertise to tackle the difficult problem of undiagnosed children,” Dr. Botto says.

According to Dr. Botto, the process for diagnosis starts by trying to understanding what is going on with the patient before jumping into testing and blood draws. He’ll spend considerable time talking to the family to get a complete story and understanding of what is going on and what’s been done so far.

Then the team sits down to review the findings and plot a way forward that is most efficient and comprehensive for a diagnosis with as few steps and time as possible. “These kids have already been through a lot,” Dr. Botto says.”They are the most complicated of complicated kids.”

When working for a diagnosis they try to scan most, if not all, of the body’s 20,000 genes to explain why a child is sick.

But beyond the scanning, the process is really a combination of clinical work and cognitive expertise together with cutting edge testing. Dr. Botto says, “All the aspects are equally important. Finding a diagnosis is not just a question of lab tests, but needs to be put into context of the child’s family history. It is the only way to make sense of the tests.”

Once they come up with a diagnosis, they come back together as a group, review the findings, and try to come up with a final assessment. “Do we have a diagnosis? Is it certain, probable, or still no diagnosis?”

The Penelope Program typically sees children with very complicated problems that have defied diagnosis from other sources. And even with all the tools and expertise of the University of Utah program, Dr. Botto says the likelihood of finding a diagnosis is 30 to 40 percent because “even with the best of tech and clinical expertise, science is not there yet to solve every situation.”

He goes onto explain, “Genetics is complicated. We don’t know all the functions of some genes. We see conditions that are new, never described before, ultra-rare. There is only so much you can say based on one family. We can make a hypothesis of what is involved, but need to compare to other families with similar clinical findings and genetic findings to start getting to the truth.”

But for the families who see results, it can mean everything.

Dr. Botto says, “Try to imagine you have a child who was perhaps doing fine until first grade. Then he starts not doing as well. He can’t walk anymore. He starts losing skills and falling behind other kids. He may have seizures. Many families go to clinician after clinician trying to figure it out. Families can go around the country to get second opinions. This is what many families call their diagnostic odyssey—an appropriate term considering the long, often hard, sometimes painful, sometimes hopeless path they take looking for answers. So, these families can finally arrive somewhere, on firmer ground, able to build a path forward based on knowledge.”

The Penelope Program has been in existence for about three years and is supported by the Department of Pediatrics and University of Utah’s Genetics, along with philanthropy grants. It is an expensive program and one not often covered by insurance. It is made possible because of the support of departments at the university and generous individuals who have supported it and believed in it since its inception.

And, going forward, Dr. Botto would like to be able to see more families.

“There are many out there who would benefit from the program,” he says, “but we have to find the funds. Part of our work is to build awareness and to provide hope for those who have lost hope.”

Nearly 10% of the world’s population has a rare or undiagnosed disease, and 80% of these are genetic in origin. Families living with these diseases can spend years on diagnostic odysseys without finding any answers. — From the video One in a Million, produced by University of Utah Health.

For more health-related articles, click HERE.