In 2016, Cottonwood Heights Police and Unified Police executed a no-knock search warrant at a Taylorsville house using explosives and battering rams. They were looking for a woman suspected of selling methamphetamine who rented a mother-in-law basement apartment there, as well as evidence of drug dealing.

The violent entry through the front door and several other entry points rousted the homeowner and her three adult sons out of their beds in their part of the residence and the four — who were never suspects, in the investigation that led to the raid — were arrested at gunpoint.

Three years later, the family members reached a settlement in their federal lawsuit alleging that the raid violated their constitutional rights. But despite what could be considered a win, Daniel McGuire, who filed the suit along with his mother and two brothers, feels that justice has eluded them.

McGuire notes that no one ever apologized and the settlement does not require any changes in procedures at the Cottonwood Heights Police Department and the Unified Police Department, the two agencies whose officers participated in the Nov. 4, 2015, operation.

“They’re human and make mistakes, but this was more than a mistake,” McGuire said. “How about an apology? How about a promise to do better from now on? How about some policy changes? How about some self-reflection and commitment to personal growth?”

But police deny they did anything wrong and say the settlement was just a way to end the case. Cottonwood Heights paid the family $60,000 in December 2018 to settle the matter; a year earlier, UPD had paid $15,000. to end its part of the case. In both settlement agreements, all of the defendants expressly denied any liability.

“They knew innocent people were in the house and decided to use explosives and put our lives at risk and traumatize us anyway,” McGuire said.

He said there are less violent ways to conduct a raid and believes the tenant could have been arrested on her way to work, rather than in an operation that expended significant police resources.

At 3 a.m. on the day of the raid, McGuire said, a loud blast that sent pieces of glass from the window flying into his basement bedroom woke him up. Thinking that home invasion robbers were shooting at him, he immediately was in fight-or-flight mode.

“I burst out of bed and banged my knee on the desk,” McGuire said. “I screamed to call 911 and ran upstairs.”

But Cottonwood police officers and UPD SWAT members were already there when McGuire, covered in glass and with his ears ringing from the explosion, got to the top of the stairs. All the family members in the house – mother and homeowner Trudy Hemingway and sons Daniel McGuire, then 36, Michael McGuire, 33, and Aaron Christensen, 18 – were quickly handcuffed.

Then they allegedly were held in freezing temperatures on the street and in the garage for more than two hours and their requests for medicine, medical attention, water, and bathroom breaks were denied while the officers searched the home. When Daniel McGuire complained about their treatment, police violated his right to free speech by threatening to jail him, according to the family’s lawsuit.

The tenant was arrested in her apartment and a search warrant return shows that a firearm, methamphetamine, bath salts, $225, a ledger and miscellaneous paraphernalia were seized. The lawsuit says no contraband was found in the family’s home. Hemingway and her sons were released and never charged in the case.

In the suit, the family alleged that a police affidavit in support of the search warrant contained false information and omitted vital facts, including that the house encompassed two residences separated by a door with a double-sided deadbolt; the tenant lived in the basement apartment, and police did not suspect any family member of involvement in the tenant’s crimes. They also said officers used excessive force and Daniel McGuire’s right to free speech right was violated when he was threatened with arrest for protesting the officers’ actions.

The suit also claimed that Cottonwood Heights Police Chief Robby Russo implemented a policy that condones constitutional violations and instructed officers to officers to stop, arrest or search first and justify the action later. Another allegation said the chief deters whistleblowers by gathering compromising information about his officers and by asking the rank and file questions such as, “Are you a rat?”

“Chief Russo reportedly fancies himself the leader of an organized crime family, with posters of famous mafia movies plastering his office walls,” the suit said.

Named as defendants were Cottonwood Heights Police, the Unified Police Department, and more than 30 officers. The suit sought an unspecified amount of money and a permanent injunction restraining the defendants from “committing such unconstitutional acts going forward.”

Lawyers for Cottonwood Heights responded that a check of Taylorsville city records had not shown separate apartments in the home or a building permit to convert part of the house into apartments. Also submitted into evidence was a photo taken at the raid that shows the door between the mother-in-law apartment and the rest of the basement was open.

And, the police affidavit said, a no-knock warrant was necessary to keep evidence from being destroyed and suspected traffickers from arming themselves. In addition, her boyfriend was an enforcer for a gang and was staying at the apartment; however, he was not there during the raid).

As for the allegations of how Russo runs the department, lawyers for Cottonwood Heights acknowledged that the chief has an autographed poster from the Sopranos television series hanging in his office but denied the other claims.

Cottonwood Heights City Manager Tim Tingey backs up the chief and the officers, saying, “I feel our police department is very well run.”

By the time the suit went to trial in December 2018, most of the defendants had been dismissed and the case had boiled down to one claim, the question of whether the search was constitutional. On the second day of trial, the family agreed to accept the $60,000 payment from Cottonwood Heights.

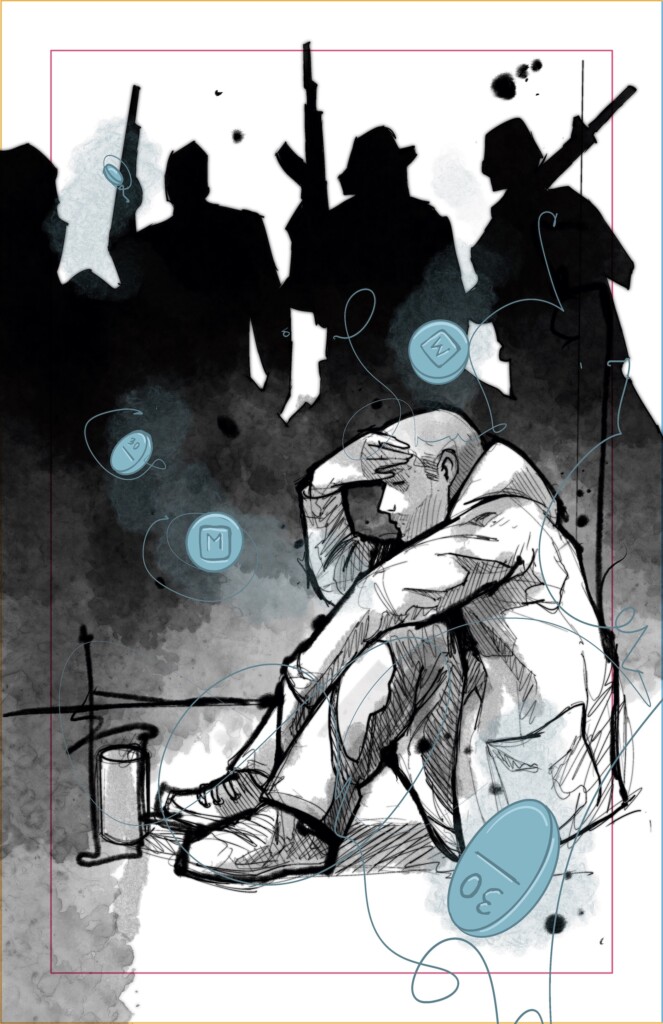

The payment ended the legal proceedings but the effects of the raid linger. Family members said in the suit that they relive that night through nightmares and flashbacks. Michael McGuire has received medical treatment for severe neck and back pain stemming from the raid.

Daniel McGuire, a musician, and activist who has been involved in a range of issues, such as protests leading up to the Iraq War, said he feels betrayed by the people “who have a duty to protect us.”

“They knew innocent people were in the house and decided to use explosives and put our lives at risk and traumatize us anyway,” McGuire said. “They left us out of the warrant application entirely, leaving the impression on the magistrate that the tenant had full run of the house. They paid no personal consequences for these actions that have impacted me deeply.”

Also discouraging was the drawn-out court battle and the dismissal of some defendants and claims on the basis of qualified immunity, he said.

“The process takes far too long to feel just and there are too many legal protections for them when they harm people,” McGuire said. “It’s retraumatizing and feels at several steps like ripping a scab off a healing wound to bleed again. I wouldn’t wish the litigation process on any victim.”