Will the “city between the canyons” lose its charm?

As any parent knows, when a teenager grows into adulthood, there are growing pains, arguments, misunderstandings, missteps. The same is true when “the teenager” is an entire community—a once semi-rural area that is growing into a mature suburb, next to a city. The “emerging adult” wants to make its own decisions, be treated with respect, and be free from top-down control. But in the process, it can make big mistakes and ruffle a lot of community feathers.

Take Cottonwood Heights, Salt Lake County’s newest city, incorporated only nine years ago, with a population of 34,000, located between Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons, east of Midvale, north of Sandy, south of Holladay. Like West Valley City and Holladay that incorporated as cities before it, Cottonwood Heights wants more local control to handle its own issues. But some say Cottonwood Heights has gone the most rogue in stretching its adult wings. It has its share of controversies and at least one big snowball in its face.

This winter the new city allowed a private company, Terracare Associates, to provide snow removal services, with disastrous results. Four days after this year’s first storm, Fort Union Boulevard was covered with a sheet of thick ice.

City fathers say they have the snow removal situation under control now but other controversies still hang in the air, mainly the city’s new police department and a proposed big development where the Canyon Racquet Club used to stand.

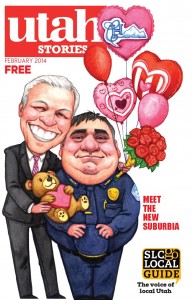

These issues are being pushed by Cottonwood Heights Mayor Kelvyn Cullimore, one of the area’s wealthiest residents with one of the largest businesses in the city. Cullimore owns a medical supply company called Dynatronics. He spearheaded the effort to incorporate the area from Salt Lake County in 2003 for more local control. He felt the schools should be controlled locally and zoning laws should be made locally. He felt the specific services the city needed were lacking and it was too much for the county to handle. At that time, Cullimore pledged no aspirations to try to handle snow removal or to create a city police department.

The Break From Salt Lake County Police Department

His ideas about the police issue changed in 2006. Cullimore, along with his “top cop,” then-Precinct Lieutenant Robby Russo, began to detach the city’s public safety from the Salt Lake County to form the Cottonwood Heights Police Department. At that time, Lieutenant Russo had been working law enforcement for the county for 20 years.

According to Salt Lake County Sheriff Jim Winder, Lt. Russo’s job was to assist the county’s Unified Police Department in providing the best possible service for Cottonwood Heights. Instead, Sheriff Winder says, Lt. Russo used clandestine tactics to urge Mayor Cullimore to break away and form Cottonwood Heights Police Department.

A Sheriff Betrayed

Mayor Cullimore says Cottonwood Height’s decision to form its own police department infuriated Sheriff Winder who then retaliated by putting the mayor’s “top cop” under investigation and on administrative leave two years into the job. Sheriff Winder, however, says Lt. Russo was investigated for using county time and money to help facilitate the expulsion of county services.

Sheriff Winder continues to criticize the new police department. He says Cottonwood Heights residents were not involved in the public process in the creation of their police department. “If any resident of Cottonwood Heights would have known how much more it would cost them and what they would lose by breaking from the county police department,” the sheriff says, “they would never have gone for the plan.” Sheriff Winder says he was never asked to sit before the new city council and offer his input. The city council voted as Mayor Cullimore and Lt. Russo wanted. Without voter input a Cottonwood Heights Police Department was formed.

The new police department has not operated without controversy. Last year 2,400 residents signed a petition to end the “heavy-handed“ treatment they were receiving from the new police department. One issue that irked business owners was the fact that police used their parking lots to position themselves to issue tickets to their customers. Both 7/11 and the Canyon Inn have lost customers since.

CHPD DUI Ticketing Controversy

A second issue is the issuing of DUI tickets. Last year, Utah Stories reported that according to DUI attorney Tyler Aires, Cottonwood Heights Police Department was writing the most DUI tickets in Utah but had the worst DUI conviction record in the state. Mayor Cullimore’s response was, “I’m proud of my police department’s record.” They had received an award from the state of Utah for safe roads.

Utah Stories attempted to gain access to the actual record of DUI cases dismissed in court. We filed a Freedom of Information Act Request. On its own submission paperwork, it reads that, by law, the city will supply the requested materials in 10-15 days.

It took 45 days to comply. The record found that indeed Cottonwood Heights Police Department has the worst DUI conviction record in Utah. Nineteen percent of all of the DUI tickets issued were thrown out of court for lack of evidence. Mayor Cullimore says he will not comment on this for Utah Stories.

A third issue is getting an exact accounting of the cost of the new police department According to Sheriff Winder, Cottonwood Heights residents have lost not only their internal affairs department (which is able to conduct internal investigations into the conduct of individual officers), but they have also lost their K9 Unit, forensics, homicide, highly qualified SWAT team and, most importantly, jurisdictional communication. “If someone commits a crime in Sandy,” Sheriff Winder says, “and travels one street over to Cottonwood Heights, there is no mechanism for the Sandy or Unified Police Force to speak to the Cottonwood Heights Police Department. We are constantly stepping on each other’s toes.”

The Sheriff says when Mayor Cullimore initially pitched the Cottonwood Heights Police Department idea to the city council, he supported his argument with the findings from a hired consultant. The findings demonstrated they would save money by having their own police department. Utah Stories has attempted to track down the actual costs of the police department but has been unable to do so.

Lack of Transparency

This brings up the fourth issue with the new police department: transparency. Despite repeated attempts by Utah Stories, Chief Russo has not returned our phone calls this past year to discuss his side of the story. At the request of Mayor Cullimore, Chief Russo will not return our phone calls.He even skips meetings. One year ago, we believed we would finally have an audience with him, but only Cullimore was present. “Why aren’t we speaking to the Chief of Police?” we asked. The mayor replied, “You are speaking to him. I am his boss.”

This action—hiding from the press—befuddles Sheriff Winder. “We are public servants,” he says. “It is my duty to be talking to you right now. And it is the duty of every police chief anywhere to answer to the media and maintain a high level of transparency.”

Sheriff Winder is not shy about talking to the press about the true costs of the new Cottonwood Heights Police Department. He says the current cost to taxpaying residents and businesses is significantly higher than originally believed—25 percent greater than the original consultant estimate. “If they calculated all of their costs,” Sheriff Winder says, “including communication, legal, fleet vehicles, and all the costs which are spread between various government agencies, they will find that taxpayers of Cottonwood Heights are receiving a reduction in services provided at a much higher cost.”

Cottonwood Heights does not have its own court system, so they contract out their cases to Holladay City Courts, including DUI cases.

Despite the growing pains of the new police department, Mayor Cullimore was re-elected this past November over challenger Peyton Robinson, who campaigned for more police accountability and more public input into city matters. By a mail-in vote, Cullimore won by a 30 point margin; his vision will continue.

The Cottonwood Heights Canyon Centre Development

Cullimore’s vision includes the proposed development at the mouth of Big Cottonwood Canyon. For two years now, Utah Stories has been examining the progress, or lack thereof, of the Canyon Centre Development. The $57 million project would have a hotel, restaurant, retail and office space, a city park, a city parking garage, a public amphitheater, pathways, and a bridge to pedestrian trails that lead to the bus stop for Big Cottonwood Canyon. By all appearances, this development would provide Cottonwood Heights a nucleus away from the big boxes, chain stores and office parks.

The city council met Jan 16th to see a presentation and 3D model by the developer. Despite the fancy graphics, business owners to the south of the project remain skeptical and have felt powerless in their efforts to completely understand the nature of the project or what will happen once the first phase of a parking structure, hotel park, and restaurant areas is completed in 2016. The scary words “eminent domain” are on the minds of the business owners.

According to an article in the Salt Lake Tribune, when the Cottonwood Heights City Council met to hear public opinion on the question of whether the new city should allow the developers to form a Community Development Area (CDA), the overwhelming majority of residents opposed the idea of giving taxpayer funding to support “wealthy developers.” Yet the city council passed the CDA so that the project could include a public amphitheater, public bridges over busy roads and 400 stalls of public parking.

Business owners at the mouth of the canyon, including 7/11, The Lifthouse, The Canyon Inn, and Porcupine Pub & Grille, all chose to opt out of joining the CDA. They believed belonging to the area outlined in the CDA would threaten their businesses. The proprietors feared that once development started, their property would fall under eminent domain. Cullimore has never offered to meet with any of the business owners and explain his position, and the city has done a terrible job in communicating to the greater public. Just two weeks before the final decision for approval will be made, (at time of press), the definitive set of plans for the project are not on the city’s website nor printed in any media (other than Utah Stories).

When you look at who the power brokers are in this development, it’s easy to understand why distrust in the project has run rampant. The man who originally bought the property, Kevin Gates, couldn’t get things moving on his own so, while Gates was still the financier, he sold the property to Chris McCandless, a Sandy City Council Member, and Wayne Niederhauser, a Utah State Senator.

In short, two politician-developers are working with a millionaire-financier and a mayor-millionaire to build a private-public development. The abundance of hyphens produces a lot of fear and anxiety.

When about what appears to be an obvious conflict of interest, McCandless responded, “Yeah, it appears saucy, doesn’t it?” He says he’s been severely beaten up over this project, as well as many other private-public projects he’s developed in the past 20 years, including land near Draper Prison.

But McCandless’ reasoning and argument to make this project a public/private development makes sense to Utah Stories. The CDA will produce the most beneficial result for residents and business owners. If there were no CDA, there would not be a public trail to access a new amphitheater. There would be no much-needed massive public underground parking area for skiers. Without a CDA, there would likely be a private hotel, private offices, and a huge asphalt parking lot in the middle. The overall proposal is much better as a public/private partnership. Do the developers benefit from the CDA? Yes, but so does the public and the area.

The only aspect lacking in the project now is the same element that is missing in most new developments. There needs to be better incorporation of the project with the existing businesses. According to Cullimore, “[The existing business owners] made a huge mistake not joining the CDA. Now they are left out.” But they had reason to be distrustful. The mayor never made them believe he was really working in their best interests. They remember his police using their parking lots to issue tickets to their customers.

Cullimore’s job now should be to ensure that the existing businesses get traffic from the hotel’s visitors. The mayor could do a good job to ensure that the much promised increase in tax revenue is not only generated from the new businesses in the new development, but that the existing businesses also realize an increase in business through well-thought out integration.

For the extent of this article, we are not delving into the potential problems with traffic, bus routes, bus stops and further neighborhood issues, but there are many that need to be addressed, discussed and debated.

The “City Between the Canyons” is the current slogan for Cottonwood Heights. I would argue that nobody wants to see a “city” between the canyons. How about trees between the canyons? Or snow properly removed from nice, quiet streets?

If Cottonwood Heights is an example of a suburban area growing up to become a city, it still has some growing up to do. With the population of the Wasatch Front expected to increase by half a million people in the next ten years, many additional municipalities might go through this same transition from teenager to adulthood. In this magazine’s opinion, even if the tax base allows a suburb to become a city, it’s better to leave it up to the county to provide the most important services, but allow community councils to have more power.

————————————

Residents, concerned citizens, Mayor Cullimore and Chief Russo, we would like to hear from you on this important issue.

All of our media sources for this article can be found below: