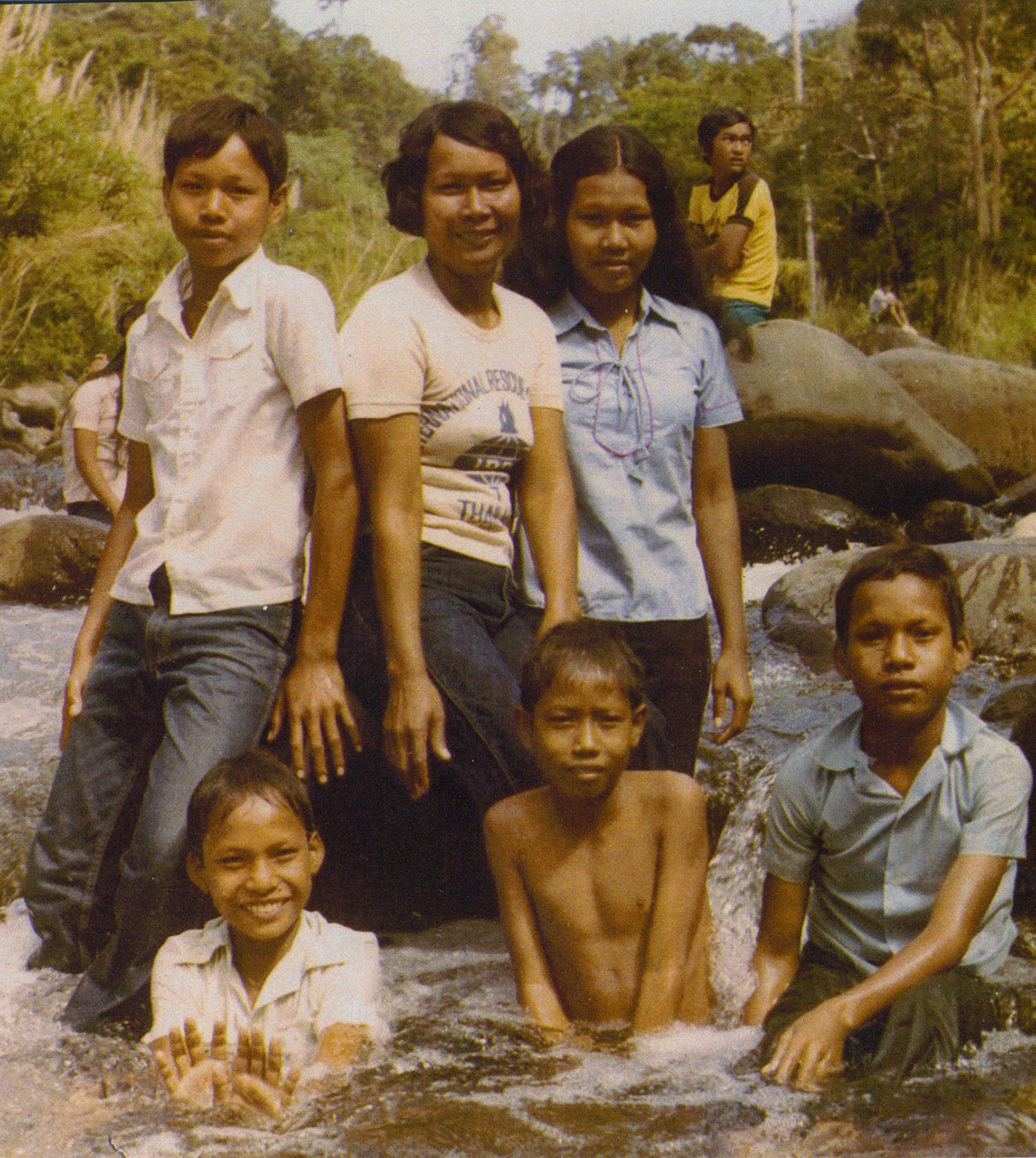

“Where we going Mom, where we going?” the kids asked repeatedly as they followed their mother day and night for about three weeks through jungles and across rivers and swamps in Cambodia. “Almost there, almost there,” lied Rem Kros to her five kids as they fled their village in Battambang Province. With swollen feet, bloody and blistered from traveling miles a day without shoes, Rem kept encouraging them. “Keep running, keep moving,” she told them, even though she had no idea where they were headed.

In the dark of night, Rem and her children had packed up what they could carry on their backs. They were told to go west and northwest, but not to go to the southeast part of the country. “My kids very good all the way to Thailand, we brought no food, no money,” says Rem.

“We had to be careful of landmines, we would follow other people’s steps when possible,” says Ran Kros, one of Rem’s sons. Thousands of Cambodians had made this journey to escape the labor camps in their villages, mostly at night to hide from the Khmer Rouge and to avoid the heat of the day. Walking over and through mounds of dead bodies was a typical part of their journey. Many people had been murdered, killed by landmines, or died of starvation or illness along the way. Their bodies were left to rot in the hot, humid climate.

The Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979 and was responsible for one of the worst mass killings of the 20th Century. The brutal regime claimed the lives of more than a million people, although some estimates say up to 2.5 million perished.

“Prior to the Khmer Rouge, we had no dreams for the future, just a simple life. We didn’t attend school. Our village was our world. America sounded like heaven when we heard about it on the radio,” she says.

Before fleeing, the family was sent to separate work camps during the day. Collecting firewood, cow tending, collecting cow dung for fires, carrying dirt to fill holes, flattening termite mounds, and using a hand hoe to level the rice fields were some of the backbreaking tasks they were forced to do from 3 am to sunset. “While working we see snails, field crabs, rats. Those are a food source. If they catch you collecting them and eating them they will kill you on the spot. Whatever they provided you, that is what you get to eat: soup rice; rice grain in water, a little pea and a lot of water, that is it,” Ran recalls.

Before being relocated to another country, refugees were sent to Sabang Morong Bataan, the Philippines to learn basic English and essential living skills.

Boarding a plane for the first time in June 1984, the Kros family flew to Hong Kong before heading to Salt Lake City, where they stayed in a high rise hotel. “Never seen a room like that, toilet, shower, never knew of them before,” says Ran.

They shared a one bedroom apartment with another family from Cambodia. “Kids had a hard time, didn’t speak the language, didn’t know the food,” says Rem.

Reflecting back, Ran says, “I was scared to go anywhere; I had never seen stop lights or traffic. To just go across the street, should I go or should I not? Even the red light, what does that mean to us? It didn’t make sense. Red light, green light, what is that? Oh, that car is coming fast.”

Rem and her children struggled to adjust to their new life. They missed the simplicity of their previous life in their village. She was thankful all of her kids were with her. “No one left behind,” she says.

Rem made sure her children studied. “Kids without school have a hard time looking for a job,” says Rem, “School very important.” Phoeun, Ry, Ran, Rong, and Reth all graduated from high school. Ran and Ry went to the police academy and are officers at the Salt Lake International Airport. Today, all of them are married and have families of their own.