It was 1942, and America was in the midst of fighting World War II. President Roosevelt issued an executive order in an effort to deflect the threat of espionage, and as a result, Japanese Americans were sent to one of 10 relocation centers, or internment camps, in America. This was not the case for German Americans or Italian Americans, however.

Topaz

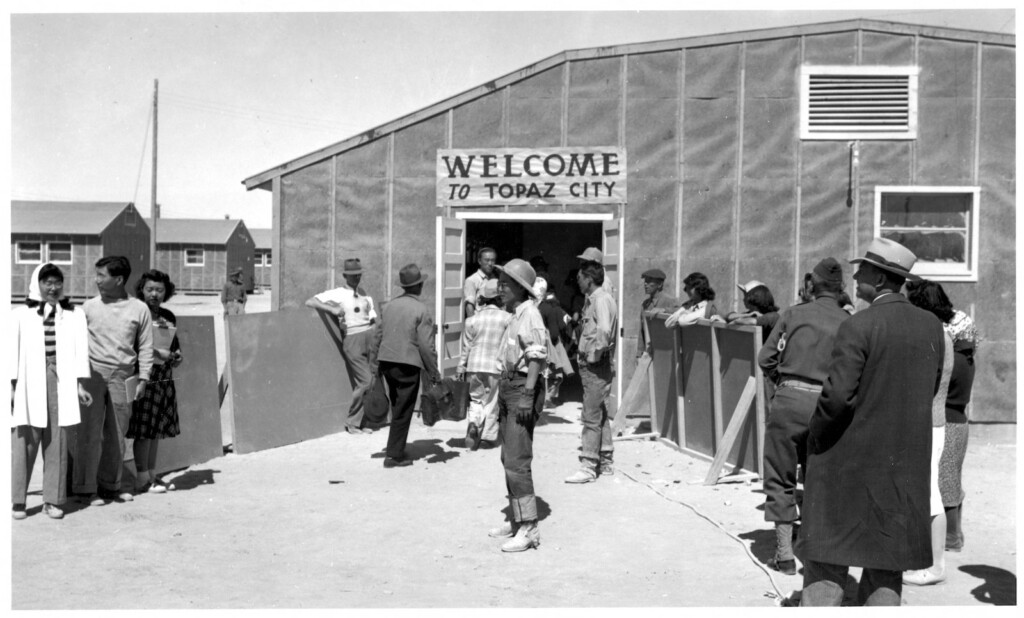

Near Delta, Utah, was a relocation center called Topaz. It was an internment camp hastily made and fraught with loss and sickness, resulting in a tragedy that would shape the lives of every Japanese American for the next three years.

The Healthcare at Topaz Internment Camp

Emma Webb grew up in Utah and is a second-year Master’s student at the University of Utah, studying history with an emphasis on the American West and Public History. Her latest research project was focused on health care at Topaz. She talks about the conditions that had to be endured.

“They built all of the housing out of green wood so by the time they finished, the houses shrunk down so there were holes in the walls. It wasn’t insulated; it was just covered in tar paper on the outside, and it was heavily overcrowded.”

About 11,212 people were processed through Topaz, according to the Topaz Museum’s web page.

Forcibly Removed

“The people, who were citizens of the United States, weren’t given any due process of law before being forcibly removed from their homes, having to sell their property when they were told that they were going to be “evacuated” from their homes,” Webb said.

People sold their houses very quickly but at a significant loss.

“People lost so much money in selling their property, making only 10 cents on the dollar because they had to leave in such a rush.”

They were forcibly taken far away from their homes with barely any money, ending up in a camp that was only half-finished.

Unfinished Hospital

“When they arrived at the camp, the hospital wasn’t finished, not opening until October of 1942. [Internees] started arriving the month before, and even when the hospital finally opened, it wasn’t complete. The first baby born at Topaz was born in the laundry room because they didn’t have a hospital set up,” Webb explained.

With unfinished housing and incomplete services, the Japanese Americans had to make do with what they had. And the environment at Topaz did, in fact, make things a lot worse.

“All they had for heat was a pot belly stove. That caused a lot of complications with people’s health from breathing in this dust [due to the topography of the camp], not to mention a lack of nutrition. According to oral accounts, nutrition was very poor. The war relocation authority allocated 45 cents per person for food each day, which was about a nickel less than the military allocation for soldiers. But then it was decreased to 31 cents for people at Topaz because they raised livestock there. They were served things like tripe and liver which were non-traditional foods that traditional Japanese people would not eat. They didn’t have refrigeration, so sometimes the food would spoil. And their water was heavily alkaline, so it was unpalatable.”

These conditions created quite the need for medical services, but there was some light in that there were plenty of people to whom they could explain their needs in the first generation’s native language and the second generation’s first language.

“At the hospital at Topaz, most of the Japanese doctors were well-respected in their fields. They were from California, so they were fully practicing, competent physicians in California before they were interned at Topaz,” Webb said.

Racism

But there was also overt racism.

“There were some Caucasian doctors as well, and what I’ve been able to tell from oral histories is that there was actually some tension between the groups, because in some situations, these Japanese-American doctors were better qualified and had more experience than the Caucasian doctors, but they had to work under the authority of the Caucasian doctors and were paid significantly less than they would have been making in their California practices,” according to Webb.

The situation took a toll on the mental health of both internees and doctors.

Dr. Harada was a practicing doctor at Topaz, and in his resignation letter in the Topaz Times, he had this to say:

“During the past 12 months, due to worries, the death of my mother, and persistent misunderstandings, my general health has become gradually undermined so much that now, due to nervous disability, I have been troubled with insomnia, anorexia, and a constant feeling of fatigue. The mental affliction has also progressed to the immediate members of my own family.”

Changes in Family Dynamics

On top of the physical and mental health toll, family dynamics were forced to change. Webb explains:

“The traditional Japanese family makeup heavily deteriorated. Parents felt like they didn’t have the traditional family dynamics that they were used to as a result of living in the camp. Rather than eating meals as a family, they ate meals in the mess hall, and their children would eat meals with their friends, so they didn’t feel like they were able to instruct their children in the way that was culturally specific to them.”

Webb’s final thoughts were on awareness and a warning to not repeat history.

“I think the real tragedy,” she said, “is that they were treated like enemies of the state just because of their race. There were no trials. There were no lawyers. They were not given the rights guaranteed to American citizens even though they were citizens.”

If we’re not careful, we could once again perpetuate violence like that in the internment camps. It comes from looking at people with fear and a gut reaction rather than with understanding and humanity.

Featured image show Japanese-Americans arriving at the Topaz Internment Camp.