“Small museum — big stories.” That’s the motto of the Moab Museum, which uses stories, documents and artifacts to preserve and share the cultural and natural history of the Moab area. Since reopening after a major renovation in 2020, the Moab Museum has been offering a variety of in-person events: tours, demonstrations, guest speakers and presentations.

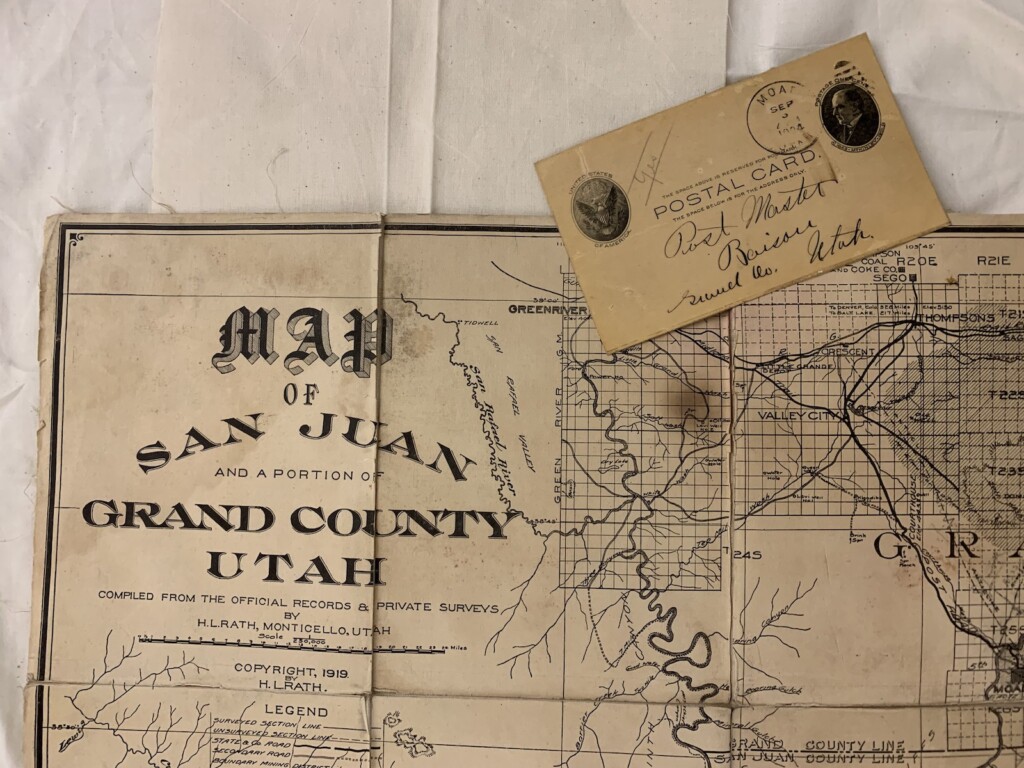

This fall, Public Programs Manager Mary Langworthy has been giving a weekly presentation on ghost towns in Grand County. She takes listeners on a journey following the likely route of a postcard addressed to the town of Miner’s Basin in 1904. The postcard — yellowed and wrapped in plastic — was sent for one penny and probably made stops at four different towns that no longer exist, before reaching its final destination in Miner’s Basin, another now-deserted settlement.

About a dozen people attended the October 17 presentation, some from Utah, others from Arizona, Minnesota, Colorado and New York. Two longtime Moab locals were among the group and added their perspective to Langworthy’s talk, sharing stories about the last resident of Miner’s Basin, who stayed decades after anyone else, and other local history.

Cisco

The 1904 postcard likely went through the town of Cisco, which was once an important railroad stop in the era of steam engines. Trains would resupply with water, and ranchers and sheepherders used it as a hub. It was a bustling town complete with stores, hotels, restaurants and a post office. Two locals in the audience remembered stopping in Cisco on their way from Moab to Grand Junction in the 1960s, when the town was still populated.

Cisco started to lose its relevance when steam engines were replaced with diesel-powered trains. In the 1970s, Interstate 70 was built several miles north of Cisco, making the town all but obsolete. It languished for decades, but in the past few years, a few people have begun to reanimate the town. There were four residents as of the 2020 census, and a store there sells general goods and vintage items. The old Cisco post office was even made available for rent on lodging websites for some time.

Dewey

The historic postcard would next have passed through Dewey, a small town that sprang up near a viable crossing of the Colorado River. Over miles of river, steep canyon walls obstruct access to the river, and Dewey is one of the few places where the approach is gradual on both banks. A few dozen people lived at Dewey, including a ferry operator, and travelers could stop at a boarding house there.

Oral histories from the museum’s archives give glimpses of daily life for residents of those bygone towns: Langworthy read aloud Martha Westwood’s recollections of preparing meals for boarders and handling mail that crossed the river on the Dewey ferry. Dewey Bridge replaced the ferry in 1916, when faster travel reduced the need for a stopping point at Dewey, and business at the boarding house dwindled. The town died away, and later the bridge burned down (as did a rebuild of it years later). Today there’s a boat launch and campground at the site.

Richardson

Richardson, Langworthy said, was so small it could barely be considered a town — but it did have a post office through which the 1904 postcard would likely have passed. Richardson was established near the mouth of Professor Creek by Sylvester Richardson, who hoped to attract more settlers to his town. He didn’t have much success though, and the Richardson post office closed down in 1905.

Castleton

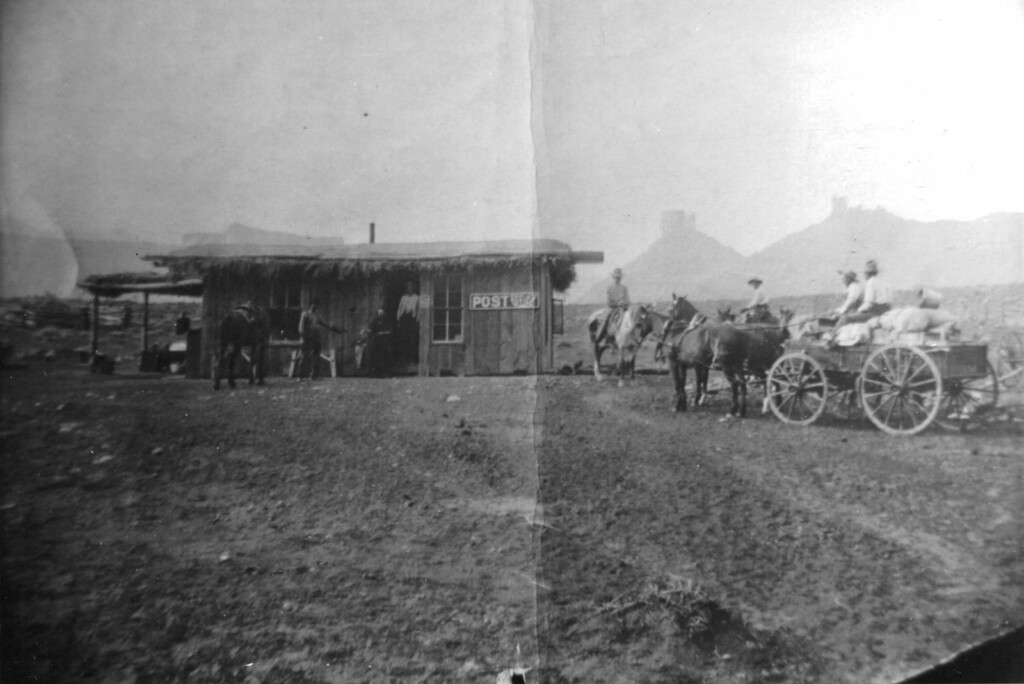

Castleton, the postcard’s last stop before its final destination, was home to a few hundred people. Ranching was a dominant industry, but the town also served as a hub for miners going to and from operations in the La Sal Mountains. Langworthy shared a historic photograph of mules bringing mail to the post office in Castleton.

Miner’s Basin

The end of the postcard’s journey, Miner’s Basin was a town of miners established high in the La Sal Mountains around the turn of the century. The two longtime locals in the audience recalled that a boy was paid to bring mail on foot over the treacherous last stretch of road to the town. Within a couple of decades, mining in the La Sals was no longer profitable, and residents left — all except one man, who stayed for many years after everyone else left. The locals in the audience remembered visiting his cabin in the 1950s while he still lived there. It was wallpapered with 1907 copies of the Grand Valley Times newspaper (which is still operating as the Moab Times Independent).

Along with photos, oral histories and maps, Langworthy shared objects from the early 1900s associated with the towns discussed. A dented and punctured pressure cooker was used by the last Miner’s Basin resident to make stew. He set the stew outside to cool, where a bear caught the scent. The bear bit through the sealed pot to get a taste.

Through objects, documents, maps and recollections, historians can piece together an understanding of what life was like in a past era. Langworthy’s talk helps answer the questions raised by the remnants of any ghost town: what happened here? Who lived here? Why did they leave? These questions continue to fascinate us, while the answers can give context and insight into our own present and future.

Visit the Moab Museum’s website, moabmuseum.org, for more information on exhibits and programs.

Feature Image by Diego Velasquez.