It only required 157 years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by Abraham Lincoln before Utah finally banned slavery in all forms.

That’s right! The Beehive State is no longer a slave state! In all seriousness now, what this ballot referendum was all about was that, While Utah’s official Constitution has a ban on traditional slavery, there was no ban of “involuntary servitude for crimes committed.” This could still be a potential sentence for criminals convicted. According to TheHill.com

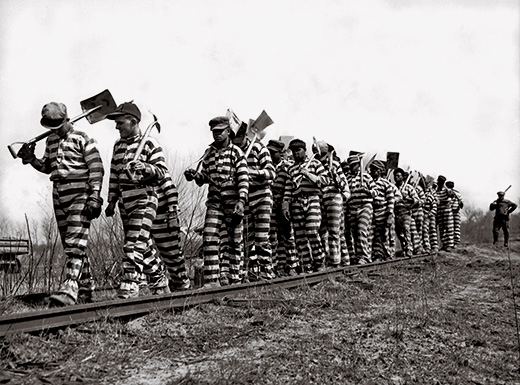

While the provision has not been invoked in recent history, it was once used to force former slaves back into unpaid labor for private parties, and later for convict leasing.

The amendment to Utah’s Constitution passed with 80% of voters voting yes and 20% of our voting to continue slavery. The 20% apparently still have slaves in their homes who they will now need to release.

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1865, says, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Last year Colorado passed the same measure, and this year both Nebraska and Utah passed these Amendments to our state constitutions.

The American Civil Liberties Union was behind this Amendment. The sponsor Jason Groth put it this way in talking to the Salt Lake Tribune:

“It would be a way to start reconciling how criminal-justice practices have been used in the past and acknowledging the way they have continued to this day,” Groth said.

After the Civil War, former slave states leaped to take advantage of the exception carved out by the 13th Amendment, the ACLU of Colorado explained last year in its case for amending the state constitution. African Americans were imprisoned and forced to labor in convict leasing programs that pumped money into the state coffers; more than 70 percent of Alabama’s revenue came from the practice in 1898, the ACLU reported.

This leads to the question: When was the last time prisons leased out their prisoners for money?

It turns out this is a fairly deep rabbit hole. I found this connected to what looks to be a PBS documentary on the topic:

After the Civil War, the South’s economy, society, and government were in shambles. Southern state governments struggled to raise money to repair damaged infrastructure and to support new expenses such as universal public education. The prison problem was especially challenging, as most prisons had been destroyed during the war.

According to a website I found called Timeline.com (this is how convict leasing ended)

The story of a young white man named Martin Tabert finally brought an outcry from the public at large. When he was 22 years old, Tabert left his North Dakota home to travel the country. In December 1921, he arrived in Tallahassee, Florida, where he hopped a train and was arrested for vagrancy. The court sentenced Tabert to 60 days in county jail, where he shoveled swamp mud in hip-deep water for 15 hours a day. Within two months, Tabert was starved and weak. Barely able to work, he was beaten with a seven-pound strap until his back “was all scabs and cuts from his shoulders to his knees.” He died. His parents were informed via letter that their son died of “fever.”

News of Tabert’s death hit the front pages, and Florida outlawed the leasing of county prisoners in 1923. Five years later, Alabama was the last state to end convict-leasing.

But some states simply moved convicts into prisons and assigned them instead to public works projects. For instance, the Tennessee Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary — which forced prisoners to work an on-site coal mine — generated significant profits and operated until 1966.

Today, African Americans are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of whites, constituting 1 million of the roughly 2.3 million people in jail. And many prisons still require inmates to work jobs like road maintenance, and cleaning city buildings. In Georgia, which ended its convict-lease program in 1908, inmates are paid $20 per day. The program saves the state an estimated $3.8 million per year.

So this now introduces the question: Is prison labor essentially slave labor? This is a hotly contested topic right now. In the language of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, it explicitly states that

“except as a punishment for crime whereof, the party shall have been duly convicted.”

According to a 2015 story by the Atlantic:

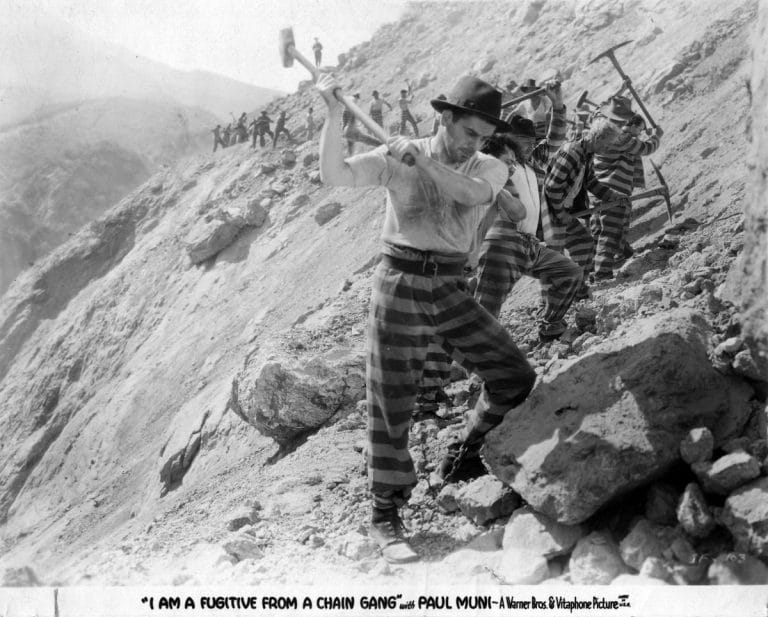

According to this Atlantic story, prison labor and convict leasing programs are still widely used in Louisiana. There was a documentary filmed about a prison program that allowed inmates to work on a farm called Angola. According to the same Atlantic article:

Over the decades, prison labor has expanded in scope and reach. Incarcerated workers, laboring within in-house operations or through convict-leasing partnerships with for-profit businesses, have been involved with mining, agriculture, and all manner of manufacturing from making military weapons to sewing garments for Victoria’s Secret. Prison programs extend into the services sector; some incarcerated workers staff call centers.

This comes as a huge surprise. I had no idea that convicts can be leased out to corporations as slaves. This actually validates the claim that one of Utah Stories Show guests claimed: Darlene McDonald, she said that slavery still exists. And that big corporations use slave labor (in the form of convicted criminals), to get a huge amount of work completed. But is this really happening?

I couldn’t find any evidence that this is happening on a wide scale. On the contrary, I found that more often prison work programs help inmates and reduce recidivism.

This is a good article that presents both sides of the argument.

–We will leave this one up to our readers and podcast listeners to see if we continue down this rabbit hole. If you are interested in this topic, please give us a like or a thumbs up, and share it with friends. If we receive enough interest we will examine how Utah Prison inmate work programs operate and what possible corporate partnerships exist that exploit prisoner labor to enrich massive corporations.