The following story was written and reported by The Utah Investigative Journalism Project in partnership with Utah Stories.

The developer of the old theatre building made questionable donations to the mayoral race

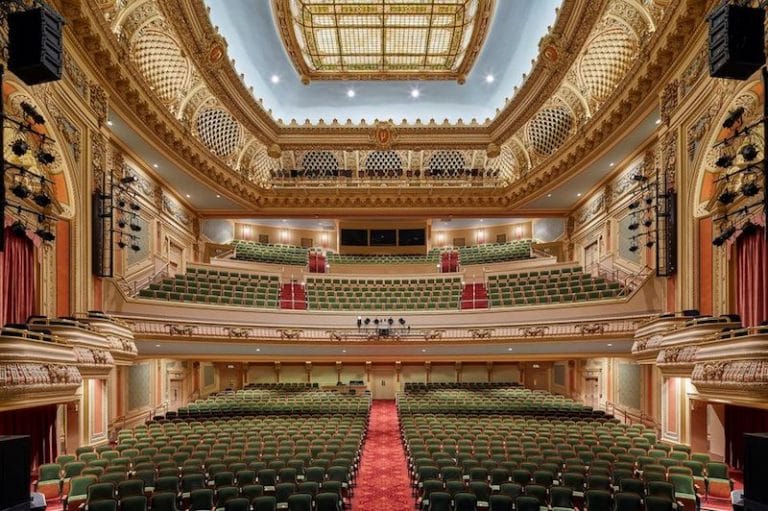

On December 3, 2019, in a crowded room in the Salt Lake City and County Building, the Save The Utah Theater group waited for a vote that would decide the fate of the historic Utah Theatre building. After months of fighting and gathering thousands of signatures, the group was worried that the old vaudeville playhouse, built in 1918 at 144 S Main Street in downtown Salt Lake City, would be torn down and its history razed and forgotten.

On the one hand, preservationists with the Save the Utah Theater group, organized by internet entrepreneur Pete Ashdown, wanted it upgraded and restored to its old glory as a downtown cultural centerpiece.

However, some city officials, put off by the estimated $60 million cost of renovating a venue that would have to compete for performances with the glittering new downtown Eccles Theater, favored selling it to developers in exchange for concessions — including low-income housing — that would benefit the public and cover the city’s $5.5 million stake in the building.

In September of 2019, then-Salt Lake City Councilwoman and mayoral candidate Erin Mendenhall, asked about “broken promises” she’d heard about from the public when it came to the theater. Despite multiple city council members expressing concern for the property, the Salt Lake City Redevelopment Agency (RDA) voted to sell the theater building to two developers for zero dollars, thereby squashing the battle for the theater’s preservation.

But the preservationists, including Ashdown (who also serves on the advisory board of The Utah Investigative Journalism Project), have cried foul and pointed to a series of what they claim are illegal campaign contributions to elected officials that preceded the vote to sell.

The Utah Investigative Journalism Project inspected campaign finance records for the 2019 Salt Lake City mayoral race and found that during the theater development decision, one of the developers of the property contributed thousands of dollars to candidates who were involved in the process — including a donation to Erin Mendenhall’s campaign two months before she voted to approve the sale of the theater for $0. During the time of the vote, Mendenhall did not recuse herself, nor did she mention the donation she received from that developer. The donation itself was potentially a violation of a city ordinance that prohibits donations from individuals negotiating work with the city, although the Mayor’s Office denies this.

The Utah Theater, formerly known as the Pantages Theater, was purchased by the Salt Lake City RDA for $5.5 million in 2010, with hopes that it would be restored to its former glory. But, in 2015, after choosing the Eccles Theater to house SLC’s new Broadway-style theater, the RDA began talks with Lasalle Group about a possible sale. The Utah-based Lasalle firm is known for owning some of Salt Lake’s most popular restaurants like the Oasis Cafe and Café Niche. In 2016, Joel Lasalle, managing partner at the LaSalle Group, expressed interest in converting the theater into a venue for “live music, a cabaret, or a dinner theater,” according to RDA memos.

The dream Lasalle had for a renovated dinner theater never materialized. Between the years 2010 and 2016, two studies were conducted exploring the viability of renovating the theater, finding the path to success was not clear, “without monumental public investment to address structural, seismic, and code compliance deficiencies,” an RDA memo stated.

One study conducted by Salt Lake County and the Utah Film and Media Arts Center, said the renovation of the theater would cost $62 to $70 million, while another study by a Chicago-based commercial real estate services company, said it would cost $61 million for full theatrical use, and $49 million for use as a movie theater.

On December 3, 2019, following multiple meetings and contentious debates since August of that year, the Salt Lake City RDA approved the sale of the Utah Theater property for $0 to the Lasalle Group and Hines Interests Limited Partnership, a real estate company from Texas that owns a property next to the theater building.

Per the deal, Hines and Lasalle were required to include public benefits such as affordable housing in 10% of the apartment spaces built, a midblock walkway next to the theater, and to provide a historic repurposing of theater elements — all of which the RDA says add up to the $5.75 million to $6.98 million that Lasalle and Hines will spend. After an appraisal in June 2019, valuing the property at $4.07 million, the RDA says the developers will end up paying millions making improvements to the site, despite the $0 price tag.

In 2019, during his time negotiating with the Salt Lake City RDA, Joel Lasalle, managing partner at the LaSalle Group, donated multiple times to candidates for Salt Lake City mayor. These donations came from Lasalle despite city codes that ban contributions by individuals with whom contracts with the city are pending.

In 2019, records show Lasalle contributed $1,000 to the mayoral campaign of state Senator Luz Escamilla (D), Salt Lake City, $500 to David Garbett, and $200 to Michael Iverson. On October 14, 2019, Lasalle contributed $2,000 to Mendenhall’s campaign.

City election laws and RDA contracts contain clauses meant to keepnich conflicts of interest from arising and improper donations from being made. Salt Lake City Code 2.46.050(H) specifically bars contributions from those under contract or seeking to contract with the city for the “rendition of personal services or furnishing any material, supplies, or equipment to the city or for selling any land or building to the city, if payment for the performance of the contract is to be made in whole or in part from city funds.”

In a request for comment about the legality of the campaign contributions, Mendenhall’s office, citing the city attorney, says that despite the developers promising the delivery of certain elements and services to the city (which would, according to contracts, more than cover the $5.5 million the city spent on the theater), the deal was not illegal.

“This contract — for the sale of real property — is not listed in the prohibitions in the campaign finance ordinance,” the attorney’s office wrote. Despite repeated attempts, Lasalle could not be reached for comment by the Utah Investigative Journalism Project.

When asked why Mendenhall didn’t mention the campaign contribution or recuse herself from the vote, a spokesperson for the mayor said only that the nature of Lasalle’s contract with the RDA didn’t prevent him from contributing to her campaign, “and was within the legal bounds set forth by the City for campaign contributions.”

“Conflicts of interest and campaign politics is as old as politics itself,” says Damon Cann, a political science professor at Utah State University, who is also the mayor of North Logan City. While the problem is old, he adds that efforts “to mitigate conflicts of interest are actually relatively new.” Some cities for example put the burden on elected officials to avoid conflicts. With Salt Lake City, the code actually puts the burden on the developer to not make donations to officials while conducting business with the city.

“I believe that most of the time most people try to do what’s right,” Cann says. “But we also know by looking at the country’s history, that at some point, people will engage in activities that are unethical.”

For investigation tips, contact our Digital Publisher & Editor at: golda@utahstories.com