One hundred and sixty-two years ago, a small-statured and often sickly thirty-six-year-old Philadelphian lawyer rode through Echo Canyon eastward to find an army and negotiate a peace in a last-ditch, unofficial effort to avert a civil war.

He’d already sailed from the east coast of the United States to Panama, where he’d ridden the railroad across the isthmus to the Pacific Ocean, boarded another ship that took him to San Francisco, then another ship to Los Angeles, where he rode the California Trail into Salt Lake City, capital of the Utah Territory.

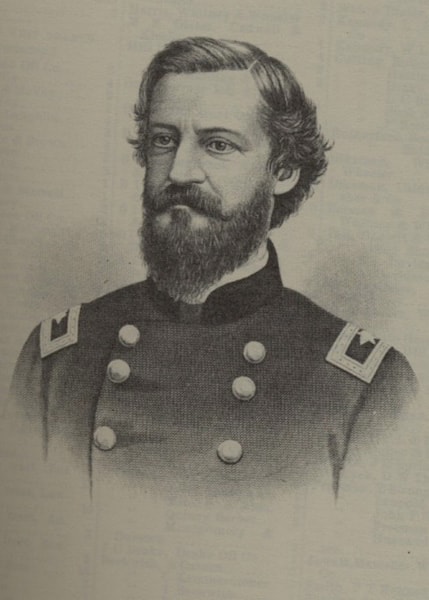

Thomas Leiper Kane was often overshadowed in life by members of his prominent family; his father, John, was a U.S. District Judge with whom the abolitionist Thomas had a falling out over the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and who died during Thomas’s journey to Utah, and his older brother, Elisha, had taken part in two well-publicized and pioneering voyages into the Arctic to try to find Sir John Franklin’s famous lost expedition before dying of scurvy and being commemorated as a national hero shortly before Thomas departed.

Kane’s mission was not a glorious one; even while most back east believed President James Buchanan had acted stupidly in his decision to send an escort 2,500 U.S. Army troops with his new Territorial Governor appointment to Utah in response to an unverified state of rebellion (although rumors of previous Governor Brigham Young’s legal misconduct were well-founded), the Mormons in Utah were still an unpopular and despised faction going back to their scandals and participation in frontier wars of the previous two decades. Both sides were seen as bad actors, but no one actually wanted a war.

It’s true that many Mormons believed this 19th century version of a Waco siege was an inevitable conflict in the last days preceding the Second Coming of Christ, and some back east believed the Mormons had it coming to them, but either side would ultimately negotiate for deescalation if an opportunity to do so and save face arose.

Just over a century later, the Cuban Missile Crisis was averted by the careful leadership of President John F. Kennedy of the United States and Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union, both whose countrymen felt reason to believe the other was evil, by following the counsel of British military theorist B.H. Liddell Hart, an influence of Kennedy’s, “Keep strong, if possible. In any case, keep cool. Have unlimited patience. Never corner an opponent, and always assist him to save face. Put yourself in his shoes—so as to see things through his eyes. Avoid self-righteousness like the devil—nothing is so self-blinding.”

In the case of the standoff now known as the Utah War, neither side appeared able to do this on their own, but after receiving permission from President Buchanan to try, Thomas Kane presented himself as a mediator. He was a member of a prominent family of Philadelphia with some political influence of his own, and was known as the “Friend of the Mormons” since taking them up as a pet cause (despite his own agnosticism about any faith) just over a decade earlier when he helped to legally arrange their migration west and form the Mormon Battalion. Thanks to him, Brigham Young agreed to step down as Governor of the Utah Territory and cede to the new Governor Alfred C. Cumming, the U.S. Army was allowed to peacefully set up operations in Utah, and a disaster was averted. Kane County, Utah is named in his honor.