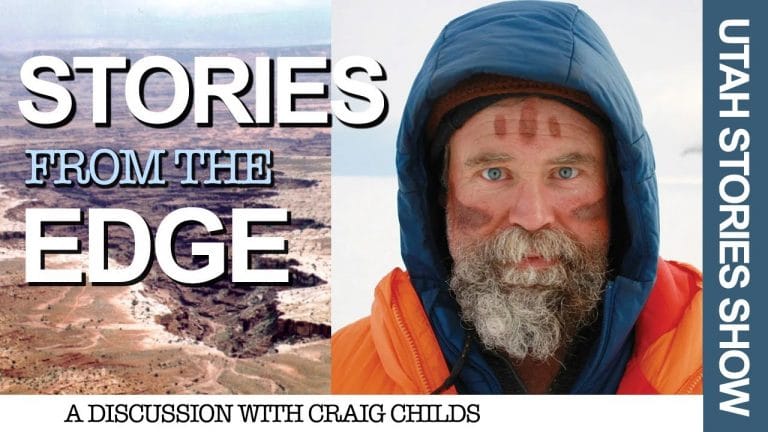

Craig Childs lives with his family off-grid in Western Colorado. He can see Utah from his house and he has explored Utah’s wilderness extensively, so we figured he qualified as a Utah Story.

When I first picked up the book “The Secret Knowledge of Water.” I was captivated by his personal adventure in understanding the Great Basin desert and remoteness at a more profound level. I’d always imagined myself spending a few weeks in the desert alone, like Everett Reuss or Edward Abbey and fully experiencing the wild. I see Childs as essentially picking up where Reuss left off. (Reuss likely drowned in a flash flood or the Colorado River).

Childs writes about water, “A desert, by definition, lacks it, but when water does come, it is magical, and sometimes in devastating abundance.”

Child’s approach in the desert is not to merely camp out and sustain, but to experience the enthralling power of flash floods by studying them up close by making a plan to live through them and tell about it. “I can be foolish sometimes, but not without confidence, I look at the situation and say to myself, ‘this is doable, I can handle this.’ I’m drawn to elemental powerful moments.” In extreme contrast to essentially riding in flash floods and living to write about it is his other skill: finding scarce water caches in the desert.

Childs experienced the expanse of the desert without packing any water. By not taking water he developed the skill of finding hidden water sources by following bees and ancient pathways and tuning his senses to the clues to find water. He described his process, “Force yourself into it. Make the story happen out of necessity…It’s a mix of stupidity, luck and skill.” he explains.

Childs has honed the skill of pitting man against the elements and nature in the basic survival scenarios that neolithic humans likely faced on a daily basis. Craig’s distinct method of both finding stories in remote areas and capturing the essence of places within geological and anthropological context make for excellent reading. My line of questioning was along the lines of how he developed his career/lifestyle and craft.

In his very early twenties he wrote a grant proposal to study the “ethnography of bush pilots off the coast of British Columbia.” He received $700 to make his proposal a reality. He hitchhiked his way up the coast of BC in airplanes, getting the stories of the pilots along the way. But he said the money didn’t come easy. The key was making his life “low overhead.”

“I lived in a teepee for about five years, with one little solar panel. It was enough to run a computer.” He lived on the land of a couple who would feed him dinner once a week in exchange for reading them his stories. “Basically that hasn’t changed. I do stories for food.”

After the teepee living he was able to get a gig as a guide taking kids from LA into Southern Arizona while writing at the same time. He lived in his truck then for about seven years. “I would do the guiding seasons, and then I would go out and write.”

His first book was written after he spent a winter in Canyonlands, where he obtained permits to see the remote areas. The book was entitled, “Stone Desert.” He met a photographer in the Needles district who proposed writing a coffee table book together.

He then visited a publisher and went with his journal where they told him, “This isn’t a coffee-table book, this is a book book. So they decided to publish his journal into a book. “It just kept going from there.”

Child’s said he did once have a “real job” when he lived and worked in Ouray, Colorado at the Ouray County Plaindealer. But he said up until then he was always, “writing on the side about things I was doing, trips I was taking.” He decided to leave the paper and head up to the Arctic to examine the Yukon and start from the Whitehorse area.

It was an ambitious adventure: to kayak the Yukon River for 50 days and 1,100 hundred miles to the Pipeline haul road area with a friend. He managed the logistics by mailing food ahead to remote outposts. He camped in remote areas where there were more animals than humans. He said he learned a great lesson, “The mosquitos were amazing. They changed my life. I can’t deal with them anymore.”

Since then he says everything he has done has been either a gig, a stint, or an assignment, never again an hourly job.

I’ve recently read, Atlas Of A Lost World: Travels In Ice Age America, where Craig examines the dynamics of people moving into an uninhabited hemisphere in the late Pleistocene, documenting arrivals from Alaska to Florida to Southern Chile.

Childs has won the Orion Book Award and has twice won the Sigurd F. Olson Nature Writing Award, the Galen Rowell Art of Adventure Award, and the Spirit of the West Award for his body of work. He is a contributing editor at Adventure Journal Quarterly, and his writing has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Men’s Journal, and Outside. The New York Times says “Childs’s feats of asceticism are nothing if not awe-inspiring: he’s a modern-day desert father.”

Childs wrote in his field notes, “Half my life ago I went to a job fair at the University of Colorado. I put on my good boots and a button-down, loaded my arms with papers I’d written and opened the door on the waiting room where intent young men and women sat wearing neatly pressed business outfits. Like me, they were waiting for their future to happen. At that instant, I spilled every paper I had, a beautiful white cascade. Scooping my life’s work off the floor as every person sat and stared, I realized I was in the wrong room. I excused myself out the door and promptly exited the job fair.”

He added, “Roads diverge in the woods and I start climbing trees.”

FOR MORE UTAH STORIES PODCASTS GO HERE.

![]()

![]()