Some people in Salt Lake City may remember a magic/novelty store tucked into a sliver of commercial space on Main St. between 1st and 2nd South. In existence as a retail establishment since the 1940’s, Loftus Novelty (now Loftus International) began wholesaling operations in the 1960’s. In the 1970’s it conducted that aspect of the business in a modest warehouse building on 400 West near Union Station.

There, in an upper floor, workers for founder and owner Gene Rose packaged rubber chickens, made and boxed disappearing ink, sorted and folded three-legged nylons (dubbed “Manty-hose”) and otherwise processed and assembled different types of magic and novelty items for shipment. One worker, from time to time, was Gene’s son, Jim Rose, whose other job was performing as a Double Bassist with the Utah Symphony Orchestra on a part-time contract.

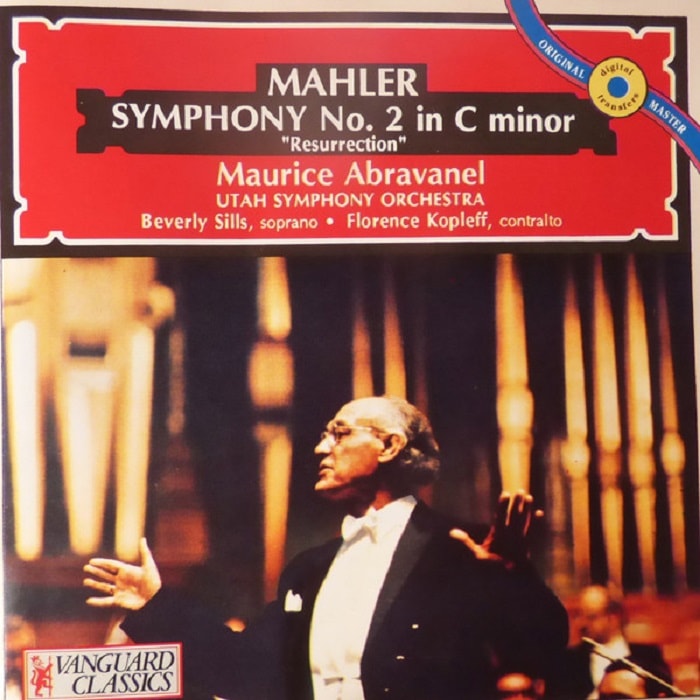

This “B” contract, as it was known, yielded a yearly salary that was 25% less than what full-time (or “A” contract) players made. By the time I joined the Orchestra in the fall of 1978, the orchestra had already released over 100 recordings (including all of the Mahler Symphonies to critical acclaim), been on several international tours, and performed in Carnegie Hall. Yet, about one-third of the musicians had this type of contract and many of us worked alongside Jim at the warehouse for some much-needed extra money. It was not at all uncommon to spend the morning rehearsing Mozart, Beethoven or Brahms with Music Director and conductor Maurice Abravanel and that afternoon be elbows deep in fake rubber dog poop.

Eventually, things began to change. What made that change possible–in addition to the solidarity of the musicians, the devotion and generosity of the Board of Directors and donors, the loyalty of the audience base, and the efforts of tireless management and staff–was the process of collective bargaining. The musicians had long been represented by their union, the American Federation of Musicians, Local 104. Indeed, since the Symphony’s inception, a contributing factor in fostering the organization’s rise from a small regional ensemble to one of national and even international recognition was the cooperation, patience and understanding demonstrated by the union. However, the issue of part-time contracts was becoming a thorn in the side of the enterprise and, by the summer of 1980, was a major stumbling block during negotiations for a successor bargaining agreement.

Though the orchestra continued to “play-and-talk,” meetings between the parties extended well past the August 31, 1980 deadline into the fall until, finally, on October 23rd an agreement was reached. Among the provisions favorable to the musicians in that agreement was one calling for the phasing out of part-time contracts, whereby all players would be full-time at the end of six years. Without the ability to bargain collectively, there is no telling when, or even if, that phase-out would have occurred.

When an employer is required to recognize the union as the exclusive bargaining agent, the increase in bargaining power gained by employees can be immeasurable. This bargaining is not always pretty; just three years later the Symphony board unsuccessfully sought a one-year freeze on the phase-out, contributing to the first strike in the organization’s history. Yet, despite the occasional bump in the road, the delicate balancing of interests that makes for a mature bargaining relationship between the parties has carried on for some eighty years despite the fact that Utah has been a right-to-work state since 1955. (*Utah’s position towards organized labor has not always been so regressive: in 1892, Utah’s Territorial Legislative Assembly made Labor Day a legal holiday, one of thirty states/territories to do so before it was made a national holiday in 1894.)

Labor Day 2018 was an appropriate time to pause and reflect that, since the end of the “B” contract phase-out in the mid-’80’s, all instrumentalists in the Orchestra have entered its ranks under full-time status. Working conditions and job security provisions that were pipe dreams forty years ago are commensurate with those across the industry. Fortunately, dedication to the process of collective bargaining by all parties in the organization has ultimately been and continues to be a stabilizing force; witness that when the Musicians began the 2018-19 season with their first rehearsal on September 4, it was with a recently negotiated and ratified agreement with a term of four years. When the contract expires it will mark eighty-two years worth of successive agreements—an on-going feat that, after all this time, is anything but a novelty.