Frank was laid off two years ago because, as his employer told him, he’s a “dinosaur.” He used to work in shipping and receiving, now he sweeps gutters and sidewalks along storefronts, shovels snow. He does this voluntarily, hoping a manager or shop owner will notice. They usually do, and when they do, they kick him a fiver. Frank figures he earns roughly fourteen cents an hour, which he strictly uses for nicotine, his one daily necessity. Once every few weeks he splurges on meth. As for food, he finds what he needs from the dumpsters, often fresh and sealed.

Frank is owed a pension, but he can’t get it. Payroll won’t dispense it unless Frank has both an address and a bank account, but he can’t get either of those without the money. Catch-22.

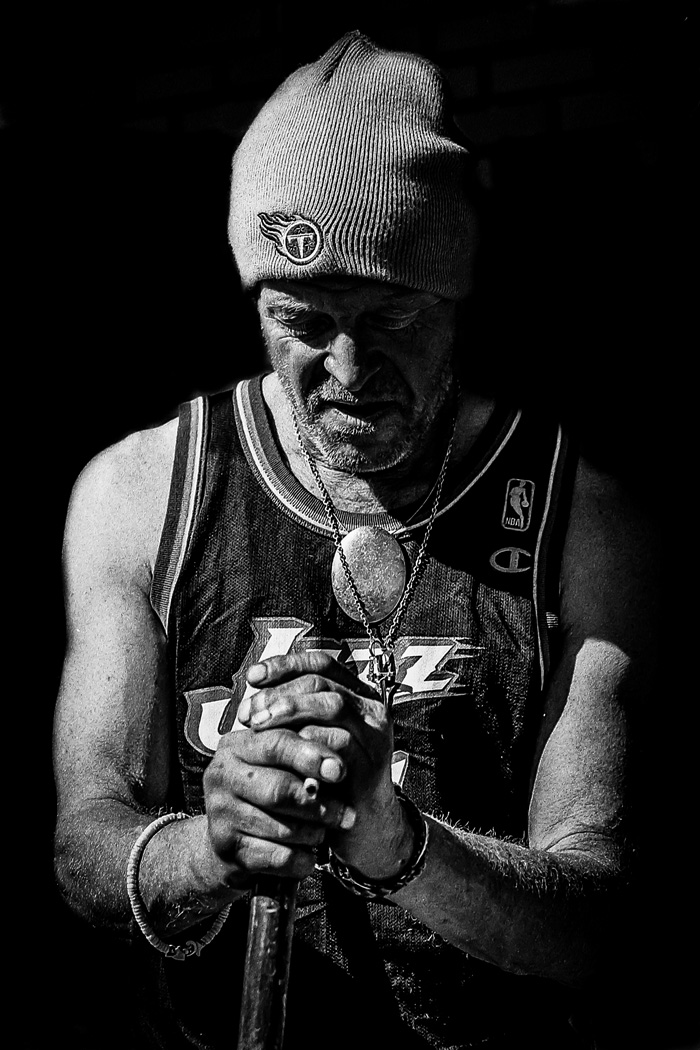

“This store is good to me,” he says, speaking of the Watchtower Cafe, where he is sweeping out front. “I get way down in the cracks.” The cracks are full of cigarette butts. Frank sees one that still has some tobacco in it. He picks it up and lights it. The sidewalk is broken, old, and sturdy, and thanks to Frank, presentable. Much like Frank.

Being reliable and presentable is important for getting work, Frank explains. He has always tried to demonstrate to those that would hire him that he knows how to work hard. He used to line up with Mexicans in the mornings, and he’d frequently get picked by someone in need of laborers. That all changed, however, when Frank began wearing necklaces and bracelets, artful trinkets he’d found on the street. He was teased for being gay, though he isn’t. Now when the trucks roll around looking for laborers, Frank is left standing there with his black brothers.

But he isn’t going to change who he is, refrain from expressing himself in whatever limited way he can, in order to appease those who would judge him solely on appearances. Hell, his trinkets are his only form of self-expression. His tank top hails from a dumpster, and his pants, well, those he stole from a sleeping woman. They are insulated. His shoes, mismatched, were made in China. They cover his feet, but if it were up to Frank, he’d wear something made in and by his community.

Today, instead of standing curbside, waiting to be ignored, Frank picks a curb and goes to work—with his broom. Often, he is still ignored.

His college degree doesn’t help much. Frank studied communications, had dreams of DJing. He knows everything about sports, can ramble off stats. But he can’t tell you what happened yesterday, because of the drugs. He mostly lives clean today, but his memory remains faulty. “See, I’ve already forgotten your name,” he teases.

While talking of the youth who die daily on the streets from overdoses, the deaths you don’t hear about on the news, Frank weeps briefly. The springtime air dries his tears. He explains that he shows his emotions openly, something his mother taught him to do, and he’ll never apologize for doing so. This, he presumes, is another reason why some judge him gay. “I was raised by women,” he says. Coincidentally, Frank shares his birthday with International Women’s Day. He turned 57 on March 8, and he is happy to share the day. In fact, he basks in the coincidence, in whatever it might signify.

On March 7, Frank flew a sign for the first time since becoming homeless. He’ll never fly a sign again, he says. He didn’t get a dollar, and even if he had, it wouldn’t have bought back the self-respect he’d given up.

Frank has tried the homeless shelter, too, but he can’t bear it. He can’t bear to see the children there. He can’t bear the innocence and sunlight dancing in their eyes while they wrestle and play. He can’t bear to see them amidst the needles entering veins, the scattered feces, the men slowly dying on bunks. The paradox is too much, the life swirling betwixt the death, the unraveling of supposed opposites. The coexisting forces.

It’s just too much, Frank laments. He knows which force has the best chance of winning over a child born into that world. He sighs, bows his head, holds close his weathered broom and broken cigarette.