Utah’s Underground Legacy

Utah’s Underground Legacy

Utah’s mining history is rich in ore, lore, and gore. Tales of lost mines guarded by winged seraphim and the spirits of Native American warriors have become the stuff of legend, recounted in campfire tales at Boy Scout camps and lauded by authors eager to exploit the greedy tendencies of gullible readers. It’s fascinating stuff, and fables, true or not, take on a life of their own, nurtured by repetition and fed by our lust for mystery and adventure. But Utah’s mining past is very real, and some of those stories are true.

Mining towns like Frisco, Jacob City, Ophir, Gold Hill, Temple Mountain, Silver Reef, and dozens of others, are little more than skeletons of their glory days—ghostly reminders of a rough and rowdy past when men lived and died in the pursuit of treasure—when a pick and shovel, a little black powder, and a lot of luck and sweat were all a man needed to extract a living from the earth; when wealth and prosperity were always just a shovel-full away. Hard rock prospectors were a hardy breed, and some of these men amassed great fortunes. Others lost everything.

Since the reign of Brigham Young as territorial governor from 1850 to 1858, mining was an integral part of Utah’s early growth and the foundation of its economic structure. This occurred despite a prohibition against prospecting by members of the Mormon Church, but the California Gold Rush of 1849 incited a flurry of claim-staking and speculating, even amongst the faithful.

A Dangerous Pursuit

A Dangerous Pursuit

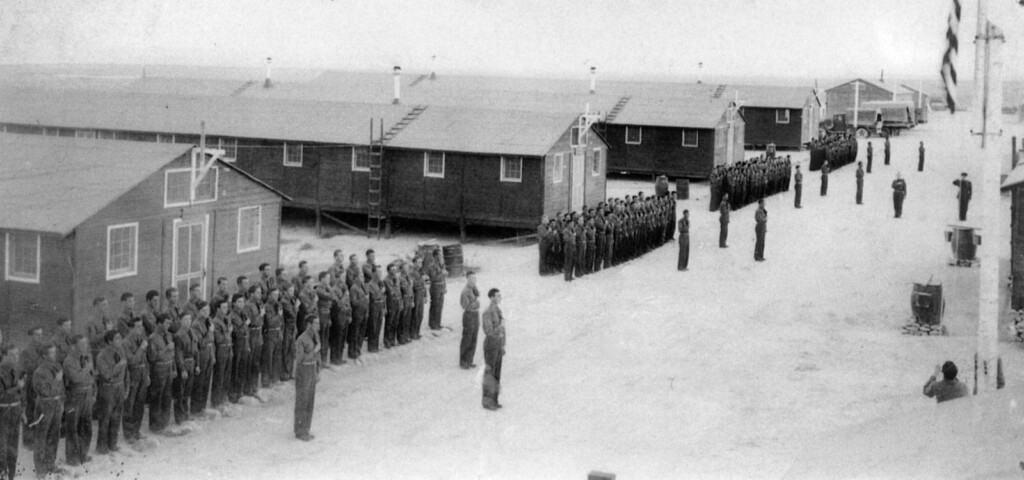

Mines in Utah began to pockmark the landscape, producing a variety of precious metals and secondary elements. Lead, zinc, copper, iron, coal, and especially gold and silver, were hard-won prizes in those early years. Prospectors and laborers alike, from all ethnicities, came to Utah seeking their fortunes. Laboring in tomb-like conditions, many of them succumbed to the rigors of hard rock and coal mining.

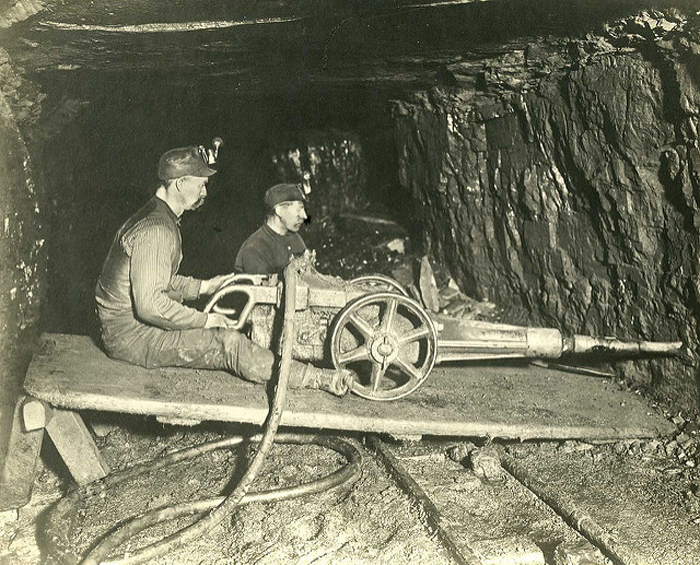

In the dusty lambent glow of open-flame carbide headlamps mounted on leather hats, immigrants from a dozen far-off countries toiled like subterranean trolls in barely penetrable darkness, plastered with layers of dust and sweat, lungs rife with the aching cough of impending disease, living and dying to strip gleaming veins of treasure that would lead them to the heart of the mountain where surely the motherlode lay in wait.

Exploited by wealthy mining moguls and capitalists like Samuel Newhouse, Jesse Knight, George Hearst, and others, miners were paid meager wages while suffering the ravages of a hostile enterprise.

Conditions in the mines were brutal and accidents were common. Fatalities resulted from methane gas and dust explosions or dynamite mishaps, and fires were a constant hazard in coal mines. Since 1900, more than 500 men have died in Utah mines, with hundreds more injured.

The worst of these occurred on May 1, 1900, when 200 men died in a black powder explosion at a mine in Scofield. A mine tunnel blast can propel man and machine through the narrow channel like a rifle barrel. The aftermath of such a loss is felt not just by miners’ families, but decimates entire communities.

Within recent memory for most Utahns is the December 19, 1984 fire at the Wilberg Mine near Orangeville, where a fire ignited by an overheated compressor killed 27 miners. The fire smoldered within the mountain for years afterward. A spiral of black smoke twisting itself into the sky was a solemn reminder of the losses suffered. A memorial occupies the site today.

Mercur—“The Town that Wouldn’t Die”

Mercur—“The Town that Wouldn’t Die”

The once-thriving town of Mercur, at the south end of the Oquirrh Mountains, began as a scrappy, hard-edged ore town called Lewiston. In the 1860s, the original lure was silver, but Lewiston died with the short-lived silver boom. Mercur’s legacy was built on the promise of gold—and that promise was eventually fulfilled after years of meager speculation.

In the 1880s, an unknown prospector discovered a vein of cinnabar, also known as “quicksilver.” Believing he had discovered mercury, he renamed the town Mercur, and began the laborious and ultimately futile process of extracting it. It turned out that the surrounding ore was rich with gold deposits, but the cost of extraction was high, and the unlucky town died a second death.

Eventually, with the right combination of financial resources and technology, Mercur began producing gold once again, becoming a boomtown in the late 1800s. A large, thriving community at last, Mercur was destroyed by fire in 1896, and again in 1902 after a rebuilding. The final blow came in 1951 when the gold dust settled and all that remained of Mercur was the haunting echo of its death rattle in the empty canyon. The town that wouldn’t die finally did.

A modern mining enterprise has reduced all traces of Mercur’s remains into rubble. Nothing exists today but a visitors center containing photos and mementos of a lost era. You can visit some of the town’s former inhabitants at the old cemetery.

Park City—Utah’s Silver Town

Utah’s most famous mining town must surely be Park City. Discovered in 1868 by army soldiers looking for silver, the quiet mountain community east of Salt Lake City quickly blossomed into a thriving boomtown with the discovery of an abundance of rich silver ore.

The promise of instant wealth prompted George Hearst to open his famous Ontario mine, which produced more than $50 million dollars’ worth of silver in its heyday. Upon the completion of the mine in 1870, the Transcontinental Railroad brought hopeful miners by the hundreds to try their hand at prospecting in Park City’s exceedingly rich, treasure-laden ground.

Like Mercur, Park City suffered a devastating fire in 1898, which destroyed nearly three-fourths of the town’s wooden homes and businesses, leaving hundreds homeless. But defiant residents rebuilt the town using brick and stone. These post-fire, turn-of-the-century reconstructions are what gives Park City its rustic charm today.

Modern Park City is known worldwide as a host for the 2002 Winter Olympic Games, Robert Redford’s Sundance Film Festival, world-class skiing, arts festivals, fine dining and resorts, but the town as we know it may not even exist today if not for its legacy, first and foremost, as a silver-mining mecca.

The Tintic District

Less renowned, but no less significant in terms of its contributions to Utah’s mineral legacy, is the Tintic Mining District of Juab County. Once comprised of the towns of Eureka, Mammoth, Dividend, Tintic Station, Silver City, and Ironton, this unique geographical region boasts a rich and colorful history. A chunk of silver ore was discovered there in 1869 by a cowboy named George Rust, and the assayed sample valued at $1,500 per ton. The resulting stampede of miners turned Eureka into Utah’s ninth largest city, with a population of 3,400 by 1910.

Writer and historian, Gary B, Speck, describes Eureka this way:

“By the turn of the century, Eureka was a real city. It had several thousand people and a long main street lined with one and two-story brick buildings … and the booming mining town had the second JCPenney store in the country. It also had a 12,000-book library, a band, an Elks Lodge, and two newspapers among its amenities.”

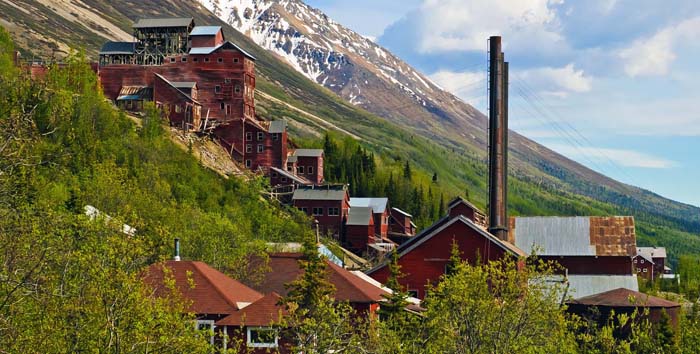

But even treasure couldn’t secure a permanent future for the area, and today, Eureka’s mine portals are silent; its sentinel structures cloaked in rust. You could spend days exploring and photographing the relics of the Tintic District’s vibrant past, making it well worth a weekend excursion.

Moab—Uranium “Boom” Town

Moab—Uranium “Boom” Town

Now considered a recreation destination, Moab is surrounded by supernal, natural beauty, attracting tourists and adventure seekers from around the world. With Canyonlands, Arches National Park, and Dead Horse Point just a stone’s throw from town, Moab has blossomed into an outdoor-lover’s playground. But it wasn’t always so.

The onset of the Cold War instilled fears of a communist invasion, ushering in the atomic age. Uranium, once a waste product of vanadium mining, became a strategic element in the U.S. arms race, and Moab had uranium. A lot of it. In fact, the entire Colorado Plateau region was infused with this radioactive element in its raw form. All that was needed was a way to extract it. The Cold War prompted a frenetic rush to produce as much bomb-grade uranium as possible in a short amount of time.

Charles Steen, an unemployed oil geologist from Texas, capitalized on the opportunity to exploit the country’s atomic gold rush along with Moab’s high-grade ore. Using oil technology, Steen struck it rich with his “Mi Vida” mine claim just southeast of Moab in Lisbon Valley. Others followed Steen’s lead, and Moab soon became the “The Uranium Capital of the World.” By the late 1950s, Utah’s uranium boom was turning prospectors into millionaires virtually overnight.

Cold war fears gradually subsided, however, and by 1962, the boom went bust. But more than 800 abandoned uranium mines still dot southern Utah’s redrock landscape, just waiting to be explored.

Roy Webb commented:

Enjoyable story about mining history in Utah. A couple of comments about it:

-You showed a photo of a Gilsonite mine but didn’t mention it. Sam Gilson was a very colorful figure, serving as a Federal Marshal, supplying horse to the Pony Express, was the Marshal at John D. Lee’s execution, and helped to chase down polygamists. Gilsonite mining was also hazardous, given how it was found in deep vertical veins. At one mine, the volatile substance caught fire, trapping two men, who were later found entombed in molten Gilsonite that had flowed around them and hardened as it cooled. The old mines are still a hazard out in the Uintah Basin.

-Not only did Eureka have all the amenities your mentioned, a library, hotels, and so on, they also fielded championship soccer teams (or Associated Football, as it used to be called) around the turn of the 20th century. Eureka teams regularly walked away with the state championship, beating teams from Salt Lake City and Price. Some years ago I got a wild notion and researched and wrote a long history of soccer in Utah, which you can find online (“The Forwards Darted Like Flashes”) and Eureka figured prominently in the sports reporting of the day.

-You also showed a photo of the potash ponds by Moab, but that mine was originally underground, until August 27, 1963, when an explosion at 2700 feet underground killed 18 miners. It was sometime after that they changed the operation to settling ponds.

Thanks again for an interesting piece,