Andrew’s eye for a particular kind of design element, the skill he uses to make manifest his imagination, and the levity that permeates his work, have earned him an established yet playful place in the serious world of art.

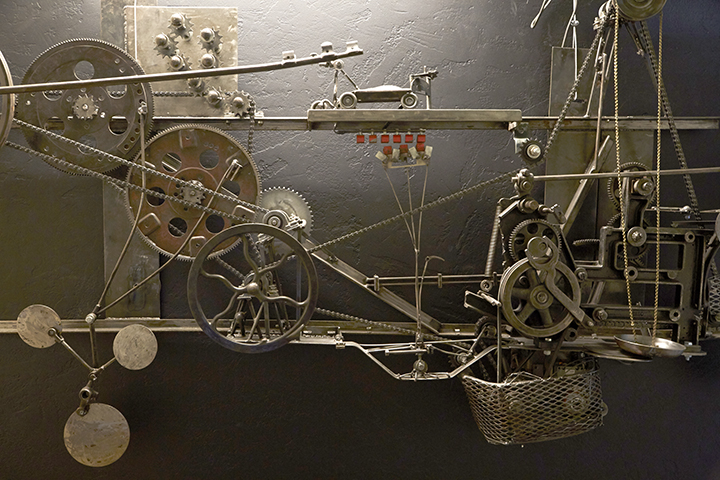

Andrew Smith’s found-object kinetic sculptures—works that spin gears, move water, twirl rotors and guide rolling balls—are a fusion of materials, science and fun. A self-taught artist-machinist-welder-craftsman, Andrew had to overcome his own self-imposed limitations when he recognized he’d identified his passion.

I realized that if I’m going to be an artist, I don’t have to be serious. I can just make stuff that’s cool. That’s enough.” Andrew asserts that his sculptures don’t express deep metaphors or political statements. Conceptually, the meaning of his art is “fun.” “It has no purpose other than itself,” he relates.

The materials Andrew grinds, welds, rivets and drills are objects that might otherwise end up at the scrap yard. Some may call it junk, but to Andrew, the uniquely shaped and rusted aviation or military equipment parts are useful sculptural elements infused with character.

Andrew’s repurposing of old sewing machine parts or pieces from defunct amusement park rides is also an exercise in preserving the past. “Older people, or farmers who typically wouldn’t care about art often recognize and connect to some piece in a sculpture,” he notes.

Andrew’s imagination is the adult expression of the most general definition of child’s play. For him, “play is discovery through enjoying the process. You have to let go of expectations to allow yourself the freedom to discover things.”

Inherent in Andrew’s free-flowing creations are unique challenges. “Sometimes people say, ‘Oh you just play around. You just weld stuff together,’” but each sculpture, he says, is the result of “trial and error experimenting.” Without design sketches or computer modeling, Andrew allows the idiosyncrasies of the materials, the junk, to inform the design and fabrication in real time.

The process of assembling directs him to the next required item to further the emerging concept. “Sometimes there’s the ‘Aha!’ moment, like when you’re doing a jigsaw puzzle and find the right piece,” he says of locating the perfect object. Alternatively, a particular function of a sculpture, such as a steel ball bearing, dictates design materials.

Commissioned pieces can present new challenges. Andrew was tasked with creating moving robotic sculptures for Glenn Beck’s 2013 “Man in the Moon” performance at USANA Amphitheatre.

“There was so much troubleshooting and problem-solving involved in that project,” he says. For example, in order to transport the two 18-foot automatons, Andrew deduced that he must build the sculptures on their transport trailer beds. He had to calculate the design to accommodate not only the weight of the assembled metal, but also create a functional aggregate of disparate yet complementary metal pieces that could be animated. When he identified how he was going to animate the robots, he then had to learn the software that would allow him to control the digital air pneumatic cylinders.