As a young boy in junior high, Jeremy Holm knew he was hurting emotionally, but he didn’t have a name for it, nor knew who to turn to. “I didn’t know the word depression,” he said. “It wasn’t something that was really talked about.”

Now, as a 35 year old, he’s more than familiar with the name but still struggles with its effects. “I think, if only I was smarter, I would handle this differently, or if I had more faith, it would be fine,” he said.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 97,000 Utah adults suffered from serious mental illness and suicidal thoughts in 2013-2014.

This may come as a surprise given the state’s religious population, with nearly 63% percent of Utahns claiming adherence to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, according to public records. But the religion’s social attitudes may, for some, present a paradox.

“Depression is no respecter of persons,” Holm said. “You can be as faithful as you can possibly be to your religion, but depression is still going to come in, like cancer. Most religions say if you follow these teachings, you are going to feel good and be happy. The problem with depression is the way it hijacks your body and the way it produces physical feelings. If someone says, shouldn’t God make you feel better if you’re religious, it’s like going to the Huntsman Cancer Institute and saying, if you were more faithful, God would step in and you wouldn’t get cancer.”

The problem is culture versus doctrine, he said.

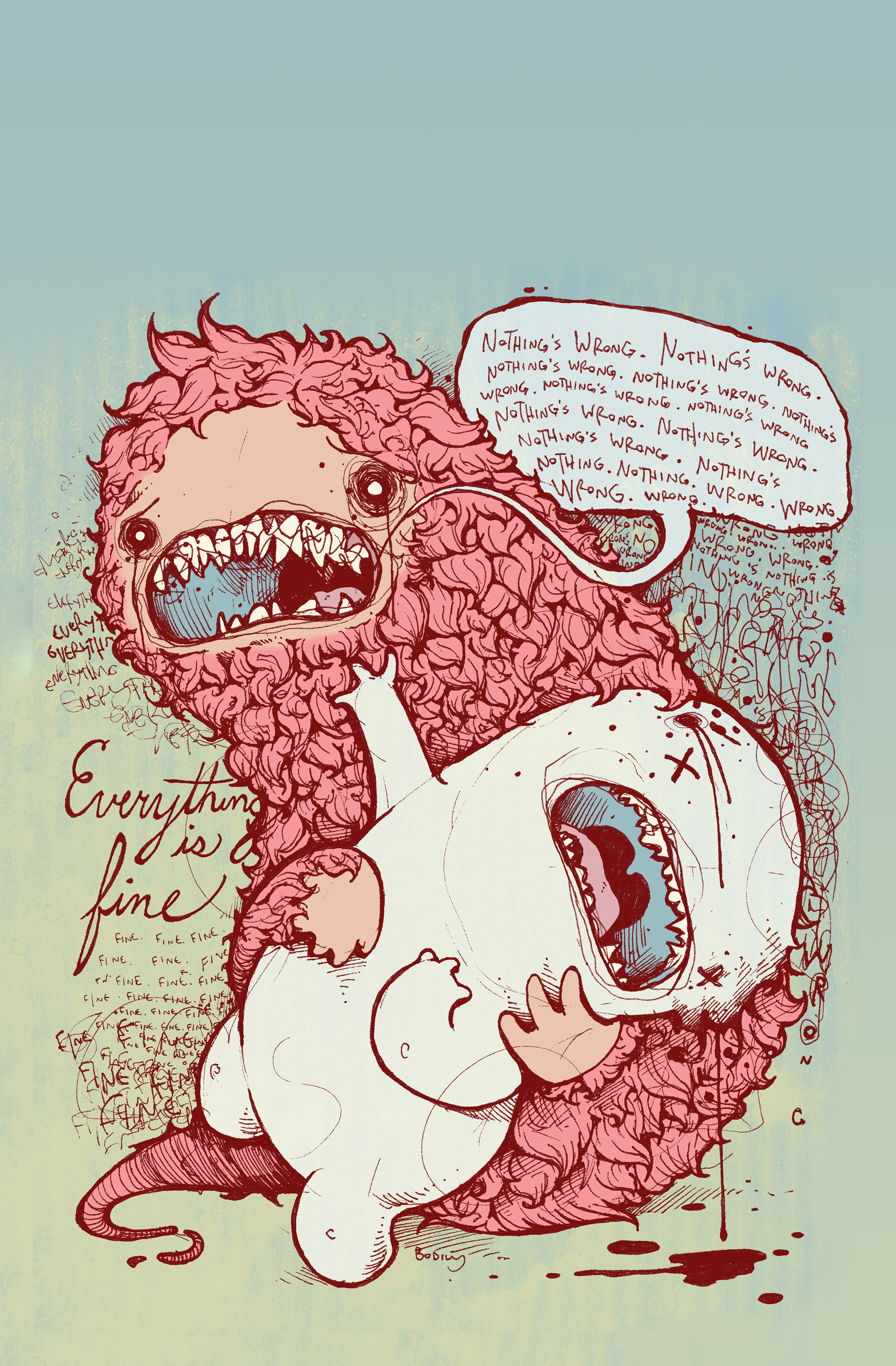

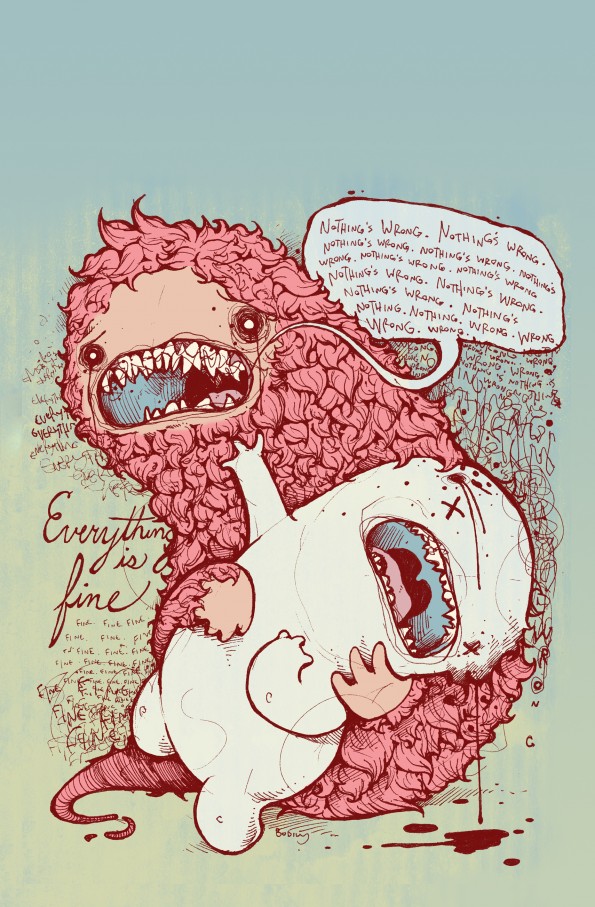

“The culture is, put on a happy face; pretend everything is ok and that you are strong and not struggling. There is that pressure to be perfect. And depression isn’t conducive to a normal lifestyle; it’s difficult to hold a job, play on a sports team and be in a relationship. So when you feel that additional pressure to be your best and perfect in all areas of your life, it can create a cycle of more depression.”

Dianna Harold has also struggled with that “perfect picture” mentality.

“I’m not really active now because I’m tired of putting on a mask of being happy and ideal all the time,” she said. “If you’re not, people judge you. I feel like I’m not your typical Mormon and I’m never going to fit into that mold, so why even try.”

Growing up, Harold was sexually assaulted, raped and abused by both men and women. “So now I have major trust issues and don’t feel like I’m worth dating. It’s a struggle even wanting to go on a date. Everybody is trying to set me up and I’m just saying no. But I’m turning 35 this year, and I realize I want a family and to be a mother. But I just don’t feel like I’m worth that because of my past.”

Harold has struggled with depression on and off since childhood, using various treatments, from therapy to medication to writing poetry.

“Therapy has given me coping mechanisms and taught me to seek help and support, but it’s still an everyday struggle that I’ll deal with for the rest of my life. Right now I’m going through one of the roughest patches I’ve had in a long time,” she said.

She has a great job and family, and makes good money, she added. “But when you’re depressed, you don’t see any of that. You see the things that aren’t going well, and that needs to stop.”

Social Worker Kazuyoshi Hayashi suggested that Utah LDS Church members might feel increased pressure from the presence of general authorities and other church leaders, which might make people feel like they aren’t reaching a prescribed lofty standard.

“It drives people in the direction of, I’m not doing good enough, whereas in other places, you might look around and think, I might be making mistakes, but comparatively, I’m not doing that bad,” he said.

Waypoint Academy Mental Health Therapist Brett Walker, said this is known as cognitive distortion, or how someone views the world around them and how they fit into it.

“Living in the past creates depression and living in the future creates anxiety,” he said. “You think about what you should have or could have done better in the past, and we’re judging ourselves. Hindsight is 20/20 so we always could have done something better. So some people just need to reframe the way they are viewing the world, identify the thinking errors they are facing, and learn the skills to overcome them and see the world in a different way.”

Walker recommends those struggling with depression have a full physical workup done to see if there is a physical reason they are depressed. “If it’s brain chemistry, no amount of therapy is going to help. It’s like going to a therapist for a broken arm.”

Counseling and medication are considerations for various forms of depression. “We are going to treat them differently because they are different animals,” he said. “A big chunk of people need a combination of both counseling and medication.”

But, according to Casherie Bright, medication can become part of the problem. She found the effect of medications to be worse than her postpartum depression. Because Bright experienced depression after she stopped nursing her first child seven or eight months after the birth, she was told that it wasn’t postpartum depression.

But, according to Casherie Bright, medication can become part of the problem. She found the effect of medications to be worse than her postpartum depression. Because Bright experienced depression after she stopped nursing her first child seven or eight months after the birth, she was told that it wasn’t postpartum depression.

“One doctor thought I was bipolar even though I never had a manic episode,” she recalled. “I had a little bit of paranoia, and schizophrenia runs in my family, so I was also told maybe that’s what I had.”

Bright said she was misdiagnosed and over-medicated. One medication made her legally blind.

“I was so medicated I could hardly function and I lost my job,” she said. “We decided to take me off the medications and I started seeing a more natural doctor, who worked with my hormone levels. And I started doing neurofeedback. But because of the medications I had been on, it took me almost two years to really recover.”

When Bright became pregnant a second time, she again experienced postpartum. This time she skipped the medications and went straight to hormone replacement and neurofeedback, plus healthy eating, exercise, and a nanny who could help take her load off. This time, she was able to function better and didn’t lose her job.

“Utah is interesting because we have a high number of antidepressant users and suicides, but we have a lower number of people doing counseling and alternative treatments,” she said. “People want help so they go to their doctor and get prescribed an antidepressant, and that’s all they do and they don’t feel better. Then, if the one doctor or the one medication doesn’t help them, they just give up.”

Bright wishes the LDS Church would take a more active role in prevention like they do with addictions.

“I think a lot of people go to their bishops and Relief Society presidents and say, I’m really struggling, but a lot of times their leaders don’t know what to do,” she said. “They try to be positive, encouraging and helpful, but they don’t have the right resources. With addictions, you are directed to one of the many addiction recovery programs held in churches throughout the valley. But for the rest of the mental health spectrum, those kinds of programs aren’t really available.”