The Walker Bank building was once the tallest building between San Francisco and the Mississippi. Locally known for its neon sign weather report–blinking red when a storm is coming and solid blue when skies are clear–do locals know much about the building’s namesake brothers? By what means did the Walkers rise to prominence and amass their fortune?

The Walkers were at one time one of the wealthiest Utah families. The brothers had a midas touch. Nearly every business venture they entered was financially successful. The Big Emma Mine in Alta, as well as nearly a dozen other mines, paid incredibly well. With their fortune they built the foundations for what would become a banking empire. Besides the Walker building, vestiges of their wealth include a South Temple and a Holladay mansion. Rob Walker was an original member of both the Alta Club and the Salt Lake Country Club.

The Walker brothers are regionally known as a counterweight to the power of the early LDS Church. They helped found the Mormon Tribune, later renamed The Salt Lake Tribune, and helped establish the Utah Liberal Party. Because of the oppression they experienced in an largely theocratic government structure, they successfully opposed statehood until government powers were more balanced.

It seems reasonable to assume that the Walker brothers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on the wings of privilege, well-educated English entrepreneurs ready to make their mark in the West. Indeed, their father, a landowner and wealthy textiles merchant, had sent his sons to the best English schools, but by the time the Walkers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1852, they were completely destitute.

Five years prior to emigrating, their father, Matthew Walker Sr. lost a fortune in railroad stocks as a result of a crash in the English market. The Walker family finances suffered, and the household had to abandon their opulent lifestyle.

In the Millennial Star, the Liverpool LDS newspaper, Matthew Walker Sr. read about the promise in the Salt Lake Valley of free land, plentiful work and the opportunity to build an ideal society poised for the Christ’s Second Coming. Matthew’s business partner, W.J. Crosby, was a talented preacher of the divinity of the Book of Mormon. Crosby convinced Walker that their circumstances would improve by converting to Mormonism and joining the Kingdom of Zion. In 1849, Walker became a member of the church.

Thousands of converts made the transatlantic and overland trek. Ship hulls tightly filled with immigrants were often incubators for disease, though Matthew Walker was not aware of this likelihood when he sent his family on board a vessel in February of 1850.

The Perpetual Emigration Fund

The Latter-Day Saints’ “Perpetual Emigration Fund” allowed new converts to travel without paying more than half of the total transportation cost. The fund was “perpetual” because immigrants agreed to pay back the money owed after they settled in the Salt Lake Valley and began earning income. Immigrants, however, would still need money for food and provisions along the way. Matthew Walker saved for two years, but his savings proved insufficient.

Matthew’s wife, Mercy, and their children arrived safely in New Orleans. With Matthew’s subsequent crossing, the family was reunited in St. Louis, however his arrival was met with despair. On the voyage, Matthew had contracted tuberculosis and his health had greatly deteriorated. Weakened, and without money to pay for proper care, Matthew and his family still had to generate income in a city burdened with immigrants and westward bound travelers. Lodging was scarce, food expensive; and a cholera epidemic was spreading.

Matthew taught his boys how to buy wares at port and sell them in the city and surrounding camps. They were able to save a few hundred dollars, in part because local merchant, William Nixon, had hired Rob and Fred to work for him.

Matthew Walker died in St. Louis at the age of 37, followed by his daughters, Mary, 11 and Emma, 9. Mercy Walker was in shock as she realized the actual cost in relocating her family to the massive western frontier. There was no time to mourn; the family needed to move. It was Matthew’s dying wish for his family to continue to Zion, so they joined the next wagon train on the Mormon Trail.

Journey West

Rob (AKA J.R. Joseph), Samuel (AKA Sharp) and David (AKA Fred) were teenagers when they made the trek; Matthew Jr. was just seven. Unable to keep pace with their westward company, the boys and their mother were left behind, but the family endured and reached Zion. They entered the valley a sorry sight, emaciated and pulling a wagon with one Indian pony and a skin-and-bones ox hauling the wagon with their meager belongings.

Ironically, the New Kingdom of Zion achieved its greatest economic success from the “sinful world” they were attempting to flee. Had it not been for the rush of California-bound gold-seekers from 1848-1855, Mormons would not have been able to sell their crops, horses and provisions at premium prices to the thousands who camped in the Salt Lake Valley along the way. At $1 a pound, flour sold for ten times the price paid back east. Boots, shovels, whiskey and tobacco all fetched premium prices.

Some of the early names involved in mercantile were William Jennings, Livingston & Kinkade, Mr. Ben Holladay and William Nixon, who would be the first steady employer of the boys both in Missouri and in Utah. The first few years in the Salt Lake Valley proved very abundant farming years. Thanks to the successful migration efforts, the pioneers had an excess of cheap labor but a scarcity of valuable currency.

While Brigham Young promoted self-sufficiency and “home industry,” these goals proved impossible to achieve in Salt Lake City. Wagon trains selling goods would regularly stop in the city, but the wagoneers accepted only federal currency or gold dust as payment for basic necessities such as nails, shovels tea and cooking utensils. While most viewed this exchange as a problem, the Walkers and other merchants saw this as an opportunity.

When the Walker brothers arrived they rented a small cabin on East Temple and 500 South. They were given a few food provisions to survive and 20 acres of farmland along Willow Creek . Sharp was the farmer in the family. Fred had been immediately rehired as a clerk by William Nixon, but his employment was temporary and sporadic.

Rob and Fred eventually were employed by the “Temple Block Public Works.” The teens helped dig the foundation for the Salt Lake City Temple. The labor was backbreaking, but they looked forward to the pay they would receive. When payday arrived, however, the young men were told they would not be paid in currency, but instead their work would be credited to them in tithing. They had been promised payment in food or clothing but were given neither. According to the book “Merchants and Miners in Utah” the family was denied Mormon scrip even after appealing to the church authorities. The boys felt abandoned and neglected by the church leaders.

Disillusioned with the church’s leadership, the Walkers nonetheless decided to stay and see what kind of future they create for themselves in the Salt Lake Valley as “gentiles” (the expression used to describe non-Mormons). They no longer attended church services nor identified with the greater Mormon population. Still, they paid a percentage of their earnings to the church, as per their emigration fund agreement, but they did not pay their tithing.

Rob and Fred found steady but seasonal employment with William Nixon, and the brothers began building a reputation for their careful accounting and exceptional foresight regarding products they bought and sold. They understood the basic laws of supply and demand, knew how to wholesale purchase the most desireable necessities, negotiate deals, and resell products at a premium. William Nixon was becoming a rich man thanks, in large part, to the Walker brothers.

Growing Business

P.J. Hickey, a traveling wholesale merchant, frequently sold to Fred Walker for Nixon’s mercantile business in Salt Lake and his expanding operations near Camp Floyd, the Army garrison established after President Buchanan sent troops to suppress a perceived Mormon rebellion. After delivering 30 wagons in Fairfield, Utah, Hickey had an additional wagon of unsold goods. Hickey offered to sell his surplus supplies to Fred Walker on credit, an incredible offer because the Walker’s still lacked sufficient purchasing capital. Fred accepted, and the brothers opened their first store in Fairfield.

The Walkers sold supplies to cash solvent soldiers at a huge premium. After less than a year, their successful Fairfield Walker Brother’s store was a Main Street fixture. Because all four brothers were involved, two could man their own store, while two could still operate Nixon’s business. It’s a credit to the brothers’ character of the brothers that they remained faithful to Nixon and made clear their intentions to open their own business, while still maintaining his.

Nixon, however, had a heavy drinking problem which caused his early death.

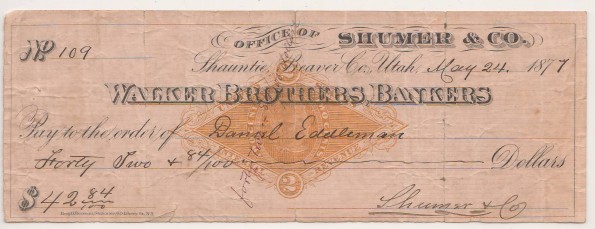

The first major expenditure the brothers agreed on was the acquisition of a heavy iron safe which they used to store items such as gold dust, coins and currency for the area merchants and soldiers in Fairfield. The trust that the community had for the brothers in handling deposits and later withdrawing their funds would lead to the brothers entering the banking industry.

READ PART II