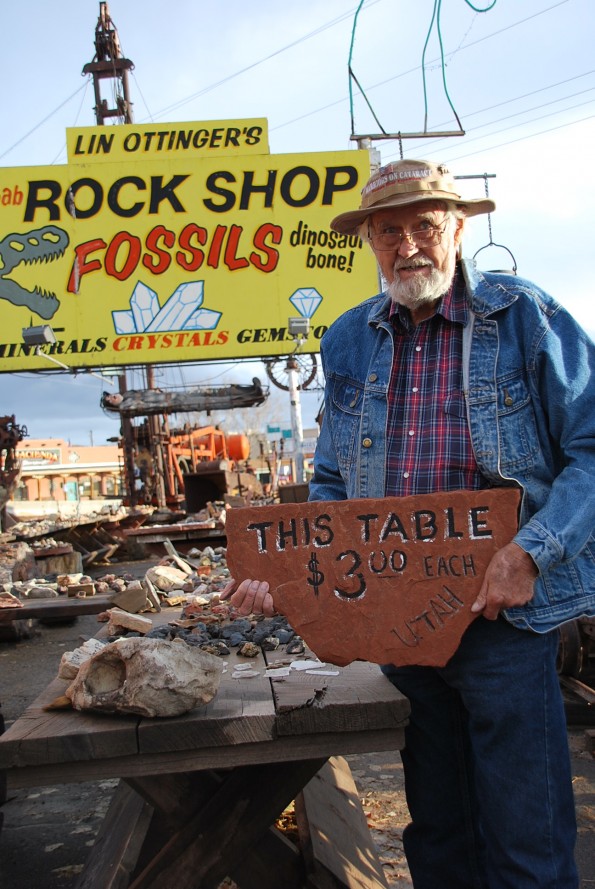

Lin Ottinger has been collecting and selling rocks since he was five. Eighty years later, he is probably the most famous rockhound in the western United States.

What Lin doesn’t readily tell those who visit his rock shop in Moab, Utah, is that his contributions to Utah’s archaeology and paleontology rival or surpass the contributions of any nearby university academics.

Lin discovered a dinosaur. After he donated the dinosaur to BYU, it was appropriately named Iguanodon Ottinger. He also discovered a human femur bone from someone who lived in the Moab area before the earliest Native Americans. The size of the femur indicates that it came from a six-foot-tall person, a discovery which does not coincide with any known, much shorter Native American tribes.

Known to everyone in Moab, Lin has been written about extensively in trade publications. But in our one-hour conversation, he had great difficulty talking about himself. Instead he wanted to talk about and show me his collections: his fossil collection, mineral collection; his bottle collection, his monkey wrench collection, and his tractor collection. It went on and on.

Lin is an exceptional man. His wife hands us a stack of articles and stories written about her husband’s long career. I inquired why he donated all of his rare specimens to BYU instead of the University of Utah, because I thought that the U had a superior archaeology and paleontology departments.

“There is a good reason for that.” Lin says. “But I’m not sure I want to talk about it for the purposes of your story.”

Any reporter knows that when someone has something they don’t want to talk about, it’s time to get your pen and start writing. Lin said, “I don’t think I want to name names, but I’ll tell you what happened.”

According to Lin, there is a man who is no longer with the department of archaeology at the University of Utah who wrote a well-known paper that basically stole Lin’s theory, without giving Lin credit. And this same professor spent his life defending his ownership of the theory.

The theory concerns how desert pools are formed and how holes are carved into the bare sandstone.

This had been a mystery to scientists for years, but Lin used different practices when studying rocks. “I let the rocks tell me their story,” he says. The story those pools told him was that they were formed by “organic acids” produced from decomposed plant matter over thousands of years. Enough acid had broken down enough sandstone to produce a hole to sustain more water, thus more plant matter grew, which increased the erosion of the rock.

Lin told the professor his theory. Later, Lin saw the paper, read it, and said he appreciated that the professor had used his theory. But when Lin pointed out that he didn’t credit him, the professor told him it was because it wasn’t Lin’s theory but his own all along. Lin terminated his relations with the University of Utah and began giving all of his specimens to BYU. He says the only reason he is willing to recount this story today is that the professor in question is now deceased.

Even after 80 years of rock collecting Lin still, “Can’t wait to get out and work.” Lin says he “works” in his shop, but out finding dinosaurs is his “pure fun.” §