Park City, UT, Main Street — On this balmy February day, moms with kids in tow are decked out in the latest in ski fashion. Couples pose for selfies, proud of their suntans. A few skiers on the hill make their way down the slopes. But the majority are here to shop, dine and enjoy the town.

I visit probably the most famous bar in town,recently featured in Playboy Magazine—The High West Saloon is packed even at 4 o’clock on a Wednesday afternoon. Sitting beside me are a group of guys in their early thirties from New Jersey who came to ski. They have no regrets for the lack of snow. “We came here because there are great restaurants, bars and usually the skiing is much better than back home.” I order an “Old Man’s Boots” (ginger beer, bitters, whiskey)— delicious and refreshing. The ambiance here feels indeed like “the independent republic” of Park City, which locals so happily boast about.

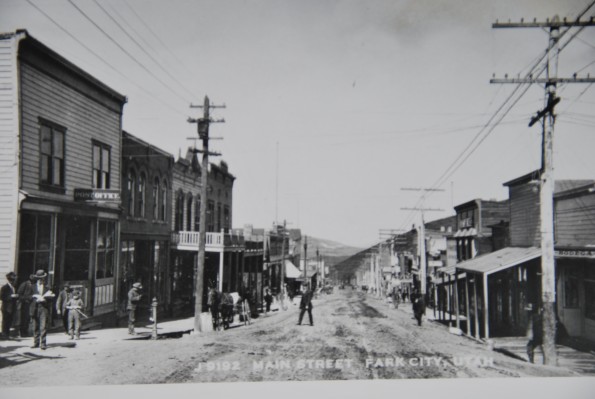

Examining Park City, we get a greater sense of the character, history and makeup of Salt Lake City since it greatly benefited from the mining fortunes produced here. This article will show where Park City has come from. It has two chapters, the distant past (1880s-1920s) and the recent revitalization (1970s to the present). Both eras depended on a plentiful supply of local beer.

The Benefits of the Mining Money Earned from Park City

Had it not been for the fortunes earned from the Park City mining industry, a great deal of Salt Lake City infrastructure would have never been built. The Holy Cross Hospital and St. Mark’s Hospital were all initially established to care for miners. “A sum of $1.50 was taken from every miners paycheck to pay for Holy Cross and St. Marks,” says Park City historian Gary Kimball.

Mining fortunes also contributed greatly to higher education. Colonel William Montgomery Ferry donated the land and building costs to establish Westminster College. John Judge’s wife Mary started a hospital to care for victims of black lung. Eventually the ground would be donated and used to build Judge Memorial High School. Several of the most significant buildings left behind by mining fortunes have luckily been saved from the wrecking ball, such as The Kearns Building and David Keith Building, as well as the Judge Building and Sarah Daft Home. Many of the ornate Victorian and renaissance revival mansions along South Temple were built with mining fortunes. Since 1937 when Thomas Kearns’s wife donated her mansion to the State of Utah, for most of that time, it has served as the Governor’s Mansion.

Park City became a boom town when Kearns, Judge and Keith established their mining empires. George Hearst (father of publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst), and Colonel Edwin F. Holmes, with his more famous wife, Susanna Bransford Emery Holmes (aka: Silver Mining Queen), were all attracted to Park City to invest their time and money. They were the lucky few who became local leaders and celebrities. They lived lives of opulence and luxury and enjoyed the high life of the Victorian era beginning in the late 1880s.

The Silver King and Ontario mines would pay out over $900,000 million over their lifetime. It’s difficult to translate this amount into today’s dollars due to inflation. But the economic impact of mining remains in the billions and greater than the impact of any other industry thus far in Utah.

Park City was just one mining town among many in Utah in the 1880s, and not the largest. The boom to bust nature of mining towns which dotted much of the West produced hundreds of ghost towns. The towns of Eureka, Frisco and Tintic all had daily newspapers and railroad lines transporting ore for processing. In their heydays mining towns were some of the largest towns in Utah, The Salt Lake Brewing Company transported beer to all of the mining towns via the railroads. At the turn-of-the-century it was anybody’s guess which towns might survive and which would die. All of these towns garnered significant investments and paid dividends for years to come.

The Early Wild West A Comparison of Park City to Frisco, Utah

An interesting contrast to Park City was the much larger Frisco located in Beaver County in the San Francisco Mountains. The Horn Silver Mine was one of the largest silver mining claims in the United States. By 1881 it was producing 1 million ounces of silver annually, the towns population was 6,500. By 1879 the United States Annual Mining Review and Stock Ledger was calling the Silver Horn Mine “the richest silver mine in the world now being worked.”

But Frisco was one of the wildest towns in the West. Shootings occurred daily. Law and order were not maintained. One writer described it as “Dodge City, Tombstone, Sodom and Gomorrah all rolled into one.”

Park City was tame by comparison. Park City had its share of shoot outs and rampant gambling and prostitution, but there was a semblance of law. Frisco was ruled by greed. Eventually the money-skimping measures caught up with the proprietors. By 1885 the Horn had produced more than $13 million and paid its shareholders $4 million in dividends. That same year the main shaft of the Horne mine collapsed. By the 1930s it was deserted. “Park City survived and Frisco didn’t because Park City had much better transportation.” says Gary Kimball. Park City had laws which were mostly respected, but others that were not.Women were not allowed to enter saloons before 1914. Occasionally exceptions were made for prostitutes, but by and large this was a law that was enforced.

Women Forbidden From Saloons

One account in the Park Record tells the story of a man who was playing a poker game with “skinners” who were con men at the town’s famous Last Chance Saloon. The man’s wife found out about the game. She knew full well that the law would be of little help, so she entered into the back of the bar, raised a chair over her head and threatened to make a scene, if all of her husband’s money wasn’t returned. The chiselers returned the money in full. Subsequently the bar owners were charged, not with illegal gambling, but allowing a woman into their saloon. They were required to pay a $10 fine.

Lasting 96 years, the Last Chance Saloon was the longest continuously-operating saloon in Park City. It featured the “hell-fire and brimstone whiskey” such as the well-known Valley Tan whiskey that Brigham Young produced. By the early 1900s “mixology” had become common, and those who could afford it purchased tastier concoctions with names such as a Tom and Jerry or Muldoon. Less reputable establishments would cut their whiskey with turpentine, ammonia and even add cayenne and tobacco to offer drinks with names such as as Tarantula Juice, Taos Lightning and Coffin Varnish.

Town news flowed in and out of the swinging saloon doors. Saloon keepers were as much peace officers as those who wore the silver stared badges. Men’s reputations were developed, known and established from their dealings in saloons. By 1905 Park City had a population of over 4,500 and supported over 20 saloons, where patrons learned about jobs and hot mining claims.

Park City flourished as a mining town until the Great Depression. Gary Kimball’s father owned and operated the Kimball Service Center, later to become the Kimball Art Center. The town’s population then went into steady decline, more buildings on Main Street were boarded up, and long-time residents feared Park City would become a ghost town.

After the 1950s, only the alpine silver mining towns of Park City and Alta remained. Park City’s mining operations didn’t completely die until the late 1970s. But due to their ability to trade gold-fever miners for powder-hungry skiers, the economic base dramatically changed.

Part II: How Park City was revitalized thanks to beer