Skull Valley, UT— Just the name portrays a Valley-of-the-Damned-image: desolate, remote. It is mostly accurate. Skull Valley is home to Dugway Proving Grounds, where biological and chemical weapons are tested for “mostly training purposes,” according to the military residents there. For most of Utah’s short history, a place beyond the Stansbury Range in Tooele County that has been neglected by developers, enjoyed by rednecks and nuclear waste proponents alike, Skull Valley has stood on its own, silent and largely unknown; however, there is much more to this place than meets the eye.

Littering the valley are discarded TVs, phone books and toys blasted to smithereens. Hundreds of red, yellow and blue shotgun shells lay scattered on the ground. OHV trails circumscribe the mountains where a small boy and girl are enjoying the fun on their mini-bike and mini four-wheelers.

“Have you ever heard of Iosepa?” I ask the family who are there riding OHVs with their children. A tall, strong lady with a nice complexion tells me her grandfather was one of the last residents of Iosepa and her uncle is responsible for maintaining the property. She is one-quarter Hawaiian.

“His name is Cory Hoopiiaina,” she informs me. “Do you want me to give him call?” She does, and he agrees to talk to me. In the meantime, we continue traveling down the road to and arrive at Iosepa. The town is gone. The only obvious evidence of the former inhabitants lie in its graveyard in which there are hundreds of plots. East of the graveyard are historic markers and a new pavilion. I’m told an annual celebration is held here every Memorial Day when hundreds of Pacific Islanders come to enjoy a luau and remember their ancestors.

Salt Lake City has the greatest concentration of Pacific Islanders in the United States. Only California has more Islanders than Utah. They dominate on our local high school and college football teams. They have big smiles, love to party by roasting pigs, and they certainly define a unique part of Salt Lake City’s culture, particularly in West Valley. It’s clear that Iosepa is a special place for them.We learn Iosepa is “Joseph” in Hawaiian, and the town was established in 1889 when it became clear that the Pacific Islanders needed to be removed from the general population of Mormons and Gentiles in Salt Lake Valley. It’s not a happy story and it runs contrary to the current “history.”

Distortion of the True Story of Iosepa

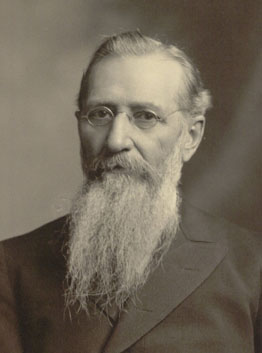

The historic markers relate an obviously sanitized, edited version of the former town’s history. If we were to believe the officially presented rhetoric, the story is cut and dry: living in a tropical paradise, a group of LDS Hawaiian converts chose to come to Utah to establish their own town in one of the most remote, inhospitable regions in the West Desert. They worked hard, many died, but they persevered and survived, and in 1911 the town won an award as “the most progressive city in Utah.” Then mysteriously, six years later, they all decided to return to Hawaii to help build the first Mormon temple in La’ie and they all lived happily ever after. The End. The simplicity of the story and the obvious defects in the logic of the memorials prompt more questions than answers. A basic search online of the questions regarding Iosepa yields the research of two scholars with links to the LDS Church. Dr. Benjamin Pykles has spent four years researching Iosepa. In 2008 and 2010 he conducted archaeological digs to uncover the town’s initial plot and streets, discover how the residents lived and study the remains of their disposed trash. BYU’s Assistant Professor of History & University Archivist J. Mathew Kester wrote his dissertation on Iosepa, recounting the severity of the bigamy and prejudice of the era. To be clear, bigotry was by no means exclusive to Latter Day Saints, but to Westerners as a whole.

Hawiian Pioneers And the Western Connection with the Sandwich Islands

Their findings paint a larger, more vibrant picture of the West, depicting the inter-connectedness of the western United States and the Polynesian Islands where Mormon missionaries began appearing as early as 1850. In Hawaii, missionaries found ready converts with a strong desire to emigrate to the “New Zion” at the base of the Rocky Mountains. At the time, however, Hawaiians were banned from leaving what was then called the “Sandwich Islands” by their King Kalākaua. By the mid 1800s the ban had been lifted, but unfortunately the popular perception of Hawaiians was that they were promiscuous sinners, afflicted by the “devil’s disease,” leprosy, an illness no Hawaiian had ever contracted before the 1830s when it likely had been introduced by Chinese immigrants. Assumptions about various dark-skinned foreigners were accepted based on religious, pseudo-scientific precepts and media portrayals. The Deseret News and The Salt Lake Tribune published insidious invectives, informing readers of the horrors of leprosy and making Islanders out to be mostly frightening, dark-skinned, leprous adulterers and savages adapted to the gentile climate of leisure and tropical fruits, and ill-suited to hard work in the harsh climate of the western U.S. Each immigrant group new to the West occupied a particular rung on the elaborate social ladder. Pacific Islanders found themselves at the very bottom rung, categorized with runaway slaves, and scrutinized even more closely. As a result, most Pacific Island converts had a very difficult time finding work or fully assimilating. Some found jobs working on the railroad or on the Salt Lake City LDS Temple, but most were required to live separately from the whites in their own neighborhoods and enclaves. This wasn’t uncommon. Salt Lake City had areas like Greek Town, China Town, Japan Town, Swede Town, and various neighborhoods defined by religion, ethnicity and wealth. Many Polynesians found homes in the Warm Springs area of North Salt Lake City.

Hawaii’s Bayonet Constitution

Still, Pacific Islanders slowly trickled into Utah via passenger boats bound for San Francisco and they came in much larger numbers after the ban on emigration from Hawaii was lifted. The Bayonet Constitution effectively annexed Hawaii as a United States territory. This by and large abrogated native Hawaiians’ right to own property. Under their new U.S. Constitution, only whites, at that time, were granted property ownership rights. Why did so many Pacific Islanders believe Utah would be a better option than their native lands? At play were a variety of factors including the strength of their newly adopted faith, having cultivated strong convictions in the Mormon missionaries’ presentation at that time, that the second coming of Christ was nearing and the New Zion would be at the epicenter of the anticipated great events; that they would enjoy forgiveness for their sins and partake in the bounty as the new “promised people.”

The First Winter in Iosepa

The settlers’ first winter in 1889 proved devastating. Whooping cough spread among the children. The people were cold, miserable, and completely unprepared for the harsh winter climate. A few of the letters addressed to Smith from one of the town’s missionaries have been translated from Hawaiian to English. In the dialogue of these accounts we glean the sentiment of both the tribulations and Joseph’s response. Smith consoles the families whose children have died, urging them to take comfort in the fact that their babies will live eternally in heaven. He encourages the people to carry on and promises that God puts only those who He loves through such difficult

trials. But, from this limited correspondence found in the LDS Church History Museum, we can conclude very little. All of Joseph F. Smith’s papers and correspondence with Iosepa have been preserved, but they are maintained under a secured status. Utah Stories has applied for access to these papers, but the form indicates it could take weeks or months before the committee determines if our purposes are legitimate or worthy of access. The letters begin to reveal the somewhat awkward relationship between the First Presidency of the LDS Church and the Pacific Islanders who professed faith in their religion but who were excluded from practicing it as their mentors or missionaries did. Hundreds of small Mormon towns were settled in the first 50 years after pioneers came to Salt Lake City, and their creation followed a customary, church-prescribed protocol. Iosepa’s social structure, however, did not exemplify the template common to the usual town-forming practices of the day. At that time in church history Pacific Islanders could not hold the Priesthood so they couldn’t conduct their own services. Instead, missionaries were sent to Iosepa, where they treated the area very much like a mission they were serving on any of the Hawaiian islands. Considering the lack of medicine, food, blankets and housing, Iosepa was an extremely difficult place for the Hawaiian pioneers to live. In addition, they didn’t have the regular means of communication through the ranks of the LDS clergy to report problems, nor did they have access to the regular provisions other members had access to.

Success Then Mysterious Abandonment

But, like many pioneer stories, the determination of the Iosepa Pacific Islanders eventually paid off and their town began producing crops and livestock. While there are very limited documents or ledgers indicating if the town was economically viable, by 1911 the town was voted “the most progressive city in Utah.” By this time culinary water had been collected from mountain springs and irrigated through cement pipelines to homes. Fire hydrants were installed and more Hawaiians were adapting and building permanent homes. Also by 1911, babies had been born and there were teenage children who knew Iosepa as their only home, having only heard stories about the remote islands from where they came. Drawings on cave walls above the town depict giant sea turtles and whales. This area is believed to have been used like a classroom teaching children about the sea creatures from an ocean they had never seen.

Unanswered Questions That The LDS Church Could Answer With Document Access

Just six years after Iosepa was showing such promise and beautification, all the residents were asked to leave. Then, President and longtime patriarch to the Pacific Islanders, Joseph F. Smith, told them they must vacate and return to Hawaii to help build the Temple in La’ie. The town’s 35,000 acres were subsequently sold by the church and all the homes, miles of irrigation canals, farms, animals and everything the Pacific Islanders built was abandoned and left to waste. Detailed records and ledgers remain in church archives under a sealed status. Utah Stories has requested access to these personal records of Joseph F. Smith and the church has declined to allow Utah Stories and other historians to gain access to answer the simple question of why? According to previous scholars Iosepa was costing the church more money than they were gaining. That for years Iospea had proven, a poor investment. But this claim runs contrary to the prior awards the town received for beautification and the ingenuity and vast network of irrigation canals that can still be seen today.

Why were the Hawaiians not given the land they made viable? Why were they told to leave after suffering so much to make the town a success? None of the research conducted on Iosepa by Dr. Benjamin Pykles nor by Matthew Kester points to clear answers. Nor does the LDS Church wish for this question to be answered. We hope the LDS Church will see that the Pacific Islanders deserve answers. History is owed an accurate accounting. “They would rather this town and this story be forgotten. They don’t want to remember what happened here,” says Cory Hoopiiania, one of the last remaining direct descendants of Iosepa. He continues to care for the cemetery and he and his non-profit association have built a pavilion where 2,000 Pacific Islanders celebrate every Memorial Day. “Without malice I say the way the church treated the Hawaiian pioneers here wasn’t right.” Utah Stories doesn’t claim that there is an intentional cover-up of facts. But as always we seek to understand the truth. §

Iosepa Today and Writer’s Notes

After this story was nearly completed I made another attempt to contact Cory Hoopiiaina. I finally reached him just a week before press. We spoke on the phone about the history about the treatment of the pacific islanders by the LDS Church and it became clear that the land of his ancestors is very much a big part of his life today. Hoopiiaina has spear-headed the projects to ad a pavilion area beside Iosepa’s cemetery. The large pavilion is now used for Pacific Islander’s celebrations. Hoopiiaina’s grandfather homesteaded on the land until his water-rights were snatched from him with a late application on posting for the BLM rights. Hoopiiaina has spent his life on this land hunting, hiking and exploring. He invited me to come see for myself the beauty and potential of Iosepa

An Attempt To Destroy History?

Today Iosepa is partially BLM Land and partially owned Ensign Ranches. There is a sticky situation between Hoopiiania and the spokesperson for Ensign named Chris Robinson. They have conflicting visions for the best use for the land today. Cory Hoopiiaina would like to see Iosepa return as a Hawaiian town, he says he know several families who would move there and begin farming if this were possible. Rancher Robinson would prefer that the land remain for his cattle and he doesn’t see the potential for another town or permanent housing.

Attempts to preserve Iosepa and the remains of the town have proven difficult. Over the years foundations of the former homes in Iosepa have been dug up and set in piles and buried. Archaeologist Benjamin Pykles confirmed that Ensign Ranches demolished one of the last standing ranch barns, despite his pleas to not do so. Hoopiiania claims that Robinson’s wish is to remove all indications that the town of Iosepa was once here — A claim that Robinson strongly denies.

Hoopiiaina expressed his desire for the LDS Church to acquire the land and donate it to the people who settled the area with their blood, sweat and tears: The LDS Pacific Islanders. Hoopiiaina took me on a tour on a four-wheeler showing me the remnants of the former saw mill. He showed me the remarkable Kanaka Lake, which his ancestors dug out by hand, then stocked with fish. He showed me the miles of irrigation canals that provided an abundance of water to orchards, fields and animals. The point of the tour was to prove a point: that the popular story of Iosepa is that the town was a economic disaster and a failure–which is the reason the church provides for why they told the settlers to vacate — is false.

Ledgers and records could provide these answers clearly, but none have been disclosed nor released by the LDS Church Library.Utah Stories has The LDS Church has recently denied Utah Stories’ request to examine the papers of Joseph F. Smith, which could provide definitive answers as to whether or not Iosepa was a causing an economic loss to the church. I believe that the success of Ensign Ranches in using many of the irrigation canals that were formerly used by the Iosepians– is proof that the Skull Valley and Iosepa had great agricultural potential and that indeed the Hawaiian Pioneers who settled there were very industrious, hard working people who made the land viable.

More information

Photographs of Iosepa from Benjamin Pykle’s Collection (Preserved and maintained thanks to the Utah Historical Society)

David Atkin’s 1958 Disertation introduction on Iosepa: A History of Iosepa The Utah Pioneer Colony

Access to Atkin’s Entire Thesis

Kanaka Lake: a small lake that the residents of Iosepa dug out by hand

Iosepa Rock Art that served to remind residents and children from where they came