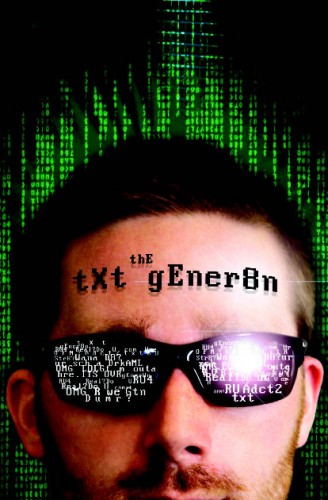

Is information overload killing American innovation?

by Richard Markosian

With a laptop, a smart phone with thousands of songs, games, movies, and apps the average college student is carrying the equivalent of hundreds of thousands of books of information around in their backpacks this year. But is access to all of this media and technology aiding learning?

Recently, I visited the Union Building at the University of Utah to hear how the students of the Information Age would answer my question. I found a table of three young men —who despite sitting together—were all separately engaged on their smart phones: a perfect focus group.

I began by asking them if their phones were a distraction when trying to study. “My phone is my connection to the world. I never turn it off,” said junior, Alex David. Another junior, Mick Summers told me, “When I first got my iPhone my grades suffered because I spent all my time texting.” Mick explained that the default setting for an I-Phone is to vibrate every five minutes when a new text message has arrived. The constant bombardment made it impossible for him to concentrate. “It was like [the phone was saying] ‘pay attention to me, justify the reason for spending all this money on me!’” Summers said despite his drop in grades, he still doesn’t turn off his phone while he is studying, but he does switch it to silent mode.

We also discussed the subject of laptop computers in the classroom. Just eight years ago when I was at the U, just a few students used laptops for note-taking. It wasn’t so much that laptops weren’t available, but at the time it just seemed like overkill. Nowadays laptops have become so cheap and small, I’m told that nearly everyone takes notes on their laptops.

“Is a laptop really necessary? Isn’t it a distraction if someone is using it to play games?” I asked. Mick replied, “I sat behind a girl in a biology class that played World of Warcraft during every lecture. I would definitely say this was a distraction. She would alt-tab to her notes if the teacher came nearby. She [deceived the teacher] with pre-written notes in a different window of her laptop.”

Alex added, “When a teacher is giving a boring lecture I can see everyone checking their Facebook pages.”

So in essence the laptops provide a virtual revolt out of sight of any teacher.

My response: “So why allow laptops and smart phones? Wouldn’t you have a better learning environment if teachers just banned them from classrooms?”

Summers said, “Even if you have a pad and pencil you can zone out and doodle, it isn’t really any different with a laptop. I had a teacher that tried to ban all texting and phones in her class, but there are kids that can send complete messages with the phones in their pockets undetected. They can sneak the phone out for a second and see the new message. It doesn’t do any good to ban technology, because kids will always find a way. . . It’s all about how the technology is used. Most students use it for good, some won’t, but it’s better to have it than not.”

I admit these guys made some good points. Banning technology from classrooms is probably impractical. But the primary problem with technology is how we are using it with “social media” and entertainment.

Information Overload

Recent studies have proven brain functioning is most effective when we focus on one task or subject at a time and is greatly hindered when we attempt to multi-task.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Stanford psychologists Anthony Wagner and Eyal Ophir surveyed 262 students on their media consumption habits. The 19 students who multi-tasked the most and 22 who multi-tasked least then took two computer-based tests, each completed while concentrating only on the task at hand.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Stanford psychologists Anthony Wagner and Eyal Ophir surveyed 262 students on their media consumption habits. The 19 students who multi-tasked the most and 22 who multi-tasked least then took two computer-based tests, each completed while concentrating only on the task at hand.

In every test, students who spent less time simultaneously reading e-mail, surfing the web, talking on the phone and watching TV performed best.

I remember in elementary school the teacher yelling out “I need everyone’s undivided attention!” Difficulty concentrating seems to be a common problem among many students. Now psychology has a solution: both a “disease” and a “cure” in calling this ADD. Certainly ADD is real in some cases, but it can be minimized in some cases by tuning out and turning off ones gadgets and devices.

When one’s minds is full of movies, games, relationships, Facebook statuses, etc., what space remains to deeply concentrate on studies? Perhaps success in today’s schools now depends one’s ability to adapt to this new environment of surplus superfluous information. This is a far cry from America’s educational foundation, which de-emphasized traditional scholarship —learning Latin, writing in long confusing sentences— and instead promoted self-education and a new form of scholarship that emphasized innovation, science and clear language.

Study Methods of America’s Original Self-Taught Scholar

Reading Benjamin Franklin’s biography one can get a sense where information and education have come since America’s founding. Despite Franklin’s desire to be a scholar, his father decided that 15-year-old Ben would become an indentured servant to his brother, who worked in the printing business. Ben’s brother was a tyrant and Franklin saw books and learning as his key to escaping his harsh life. Franklin started his own book club and lending library with 50 other like-minded tradesmen. They all contributed their books and paid member dues. Sharing information, Franklin wrote, “was imitated by other towns and in other provinces. The libraries were augmented by donations, reading became fashionable, and our people having no publick [sic] amusements to divert their attention from study became better acquainted with books, and in a few years were observ’d by strangers to be better instructed and more intelligent than people of the same rank generally are in other countries.” Information in early America was a valued commodity, and the poor quickly learned that education was their ticket to wealth, rather than lineage and social status as it had been in Europe.

A Few Things They Don’t Teach in School

It’s strange that in close to 14 years of schooling I was never offered a class on thinking or concentration. I was never assigned a chapter on insight or self education. I had to learn on my own how to think and how to concentrate.

Teachers dictate information; sometimes a discussion will ensue, but most of the time students need to learn, memorize, formulate and figure on their own, without proper instruction on how to achieve the best results.

A new concept needs space to penetrate and solidify in the mind. All the clutter and noise with which we bombard our brains inhibits this process. And we only find moments of inspiration if we allow our studies and thoughts to marinate in a quiet mind.

Proper thought marination does not happen only at the conscious level but in the subconscious. Studying before bed-time or until we are mentally exhausted then sleeping allows studies and concepts to receive the added benefit of subconscious absorption.

It’s a misnomer to call a teacher an “educator.” This would imply that a teacher has a magical ability to infuse their students with education.

Benjamin Franklin never crammed for a test, instead he tested himself by attempting to rewrite difficult concepts into his own words. He eventually found that he was actually able to improve and clarify the language of some scholars and texts. This ability eventually lead to his famous “Poor Richard’s Almanac” which offered famous phrases for good living such as “a penny saved is a penny earned,” or “what can be done just as easily today should not be put off until tomorrow.” These were actually borrowed concepts that Franklin simplified.

The best self-educators demonstrate that unless a student actively participates in the learning process, there is no education. Therefore, in a sense, all education is actually self-education. Rote memorization and the ability to pass tests is generally not directly correlated with workplace success or the ability to innovate.

In my observations of business owners, I have found that the best practice continual self-education and are open to the ideas of their customers. And the businesses that fail are usually those who fail at innovation.

The guys I met at the Union recognized that there must be much more to an education than passing tests:

“I know some students who always get straight A’s, but you try and talk to them and they don’t have anything to offer beyond their ability to regurgitate information,” said Mick Summers. The emphasis on merely passing tests is incredibly outdated. There needs to be a shift towards thought-based education, rather than memorization and regurgitation. These days any computer can spit out facts endlessly. To be competitive and successful, you have to be able to think and innovate. §