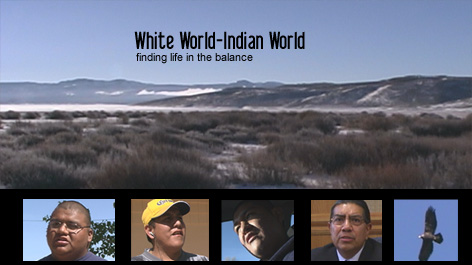

A picture of life on the Fort Duchesne reservation in Roosevelt, Utah

The Ute Indians of North Western Utah are the least-educated, poorest citizens in Utah. Most live off Government assistance and the dropout rate among their children is ninety-percent. This fact has caused them to be the poorest group of citizens in Utah. Not only are they poor and uneducated but they are also plagued by rampant drug abuse and alcoholism. One can imagine this doesn’t lead to happy well-adjusted family lives for most tribal youth. In the Summer of 2002 I set out to make a film on the young men (pictured above) They describe their family lives, their hardships and failure (all three dropped out of public high school) and their hope fore the future in finally graduating from adult education getting their second chance in life from the Uintah River Charter School.

The Ute Indians of North Western Utah are the least-educated, poorest citizens in Utah. Most live off Government assistance and the dropout rate among their children is ninety-percent. This fact has caused them to be the poorest group of citizens in Utah. Not only are they poor and uneducated but they are also plagued by rampant drug abuse and alcoholism. One can imagine this doesn’t lead to happy well-adjusted family lives for most tribal youth. In the Summer of 2002 I set out to make a film on the young men (pictured above) They describe their family lives, their hardships and failure (all three dropped out of public high school) and their hope fore the future in finally graduating from adult education getting their second chance in life from the Uintah River Charter School.

Visiting the reservation it was difficult to believe I was still in fact in Utah. Run down buildings mark the entrance to the tribal grounds. Signs reading “Ute Lanes” and “Bottle Hollow Recreation Center” look as if they were abandoned 30 years ago. Homes and yards are left un-kept and beer cans are strewn about the poor roads. However, there are a few places on the reservation that look decent. The new business center, where tribal members convinced a national call center to be locate and employ tribal members at $6.25 an hour, “a good wage considering where we are,” I’m told by Fellicia Cuch. Another bright spot is the Uintah River Charter School. This school isn’t neglected, it looks well kept. Inside students are busily working on their assignments and teachers are offering their lessons to captivated students.

Inside I meet students who are getting a lesson in Aquaculture. The tribe has teamed up with Utah State University to offer a course in raising fingerling trout from tiny eggs. Now on their third attempt students finally found success in raising the trout to maturity. Students are very excited as they create a temporary bubble bath as the fish feed on brine meal. Here I’m introduced to Davy, a stout, pimpled student in a hoodie and a yellow baseball cap. The Principal tells him to go along with me in my car up to their satellite mountain campus.

Together, in my little Acura, Davy directs me to climb up a dusty desert road. Once we pass the shanty homes the view becomes stunning. A large river caries a huge load. Evergreens are thick and we pass by a small lake. “That’s where we’re going to plant those trout,” Davy informs me. When we reach the campus we are greeted by Eric Pie. He shows me the buildings that make the campus. They are cabin-like structures with porches and screen windows. “The students help build all of this…”

Besides Davy’s story of parental neglect and a mom, “who would rather do drugs than try to raise us and take care of us.” I meet Alfred and James who are both inspirational in their overcoming their horribly broken family lives determined to scuceed. Alfred and Davy were locked up in prison for gang violence, violence is very common on the small reservation. Due to the very high dropout rate in the public schools the Tribe has taken the initiative to educate their own children. This is the six minute version of their story.

Story in Making this film

Working on this short film was indeed a roller coaster ride. I had never experienced subjects open up the way these students did when they recognized that I was there to try to capture a slice of life on “the res”. I never felt such a great feeling of accomplishment after completion of my short film. I felt I could do these terrific kids a great service by letting the world know their story and plight. The three children pictured above all have family members who have have been in and out of prison. Davy (third from the left) candidly talks about how difficult it was for him to realize that his mom, “would rather do drugs than raise him and take care of him.” This short film received some acclaim from the Utah Adult Education and the Rocky Mountain American Indian Foundation President and Director of Indian Affairs for the State of Utah, Forrest Cuch. After the success of my short film I thought this would be a perfect feature-length documentary film. The plight of the Ute Indians is a story I believe Utah citizens and the greater world should know. However, I was about to ride the coaster all the way back down into the cesspool of bureaucratic mire.

I set out to get funding to produce a real documentary that I might air on PBS. I worked with an amazing grant writer, Jenna Taylor, and for months I fleshed out all the details of what this film would become. Forest Cuch (second from right) offered to allow me to do the film under his non-profit organization the Rocky Mountain Indian Association. Forrest was great man to work with and we were all excited to see the film be made.

The final step of the grant writing process was to get the approval to do the film from the Ute business committee, otherwise known as the Tribal Council. Cameron Cuch, Director of Education for the Ute Tribe, was my liaison for presenting my film to Tribal Council and gaining their permission. Cameron told me my short film and proposal would be presented at the next meeting in April 2005. The last I ever heard from Cameron is that the education board for the business committee was unnamed and it would have to be decided as soon as they were appointed.

I sent e-mail month after month and heard nothing from Cameron. I’ve left him voice mails and he has never returned my phone calls. Still as of this day, after hundreds of hours of my time invested into the project Cameron has not called me back. About a year ago I read in the Deseret News that he is now working under John Jarrius for the Ute Energy. Jarrius is the financial advisor for the Ute tribe who is paid $60,000 per month to utilize the Utes land resources in maintaining drilling operations for natural gas and oil. Perhaps today Cameron Cuch has taken over Jarius’ position because the latest news is that the Tribal Council voted to release Jarius from his duties.

It seems Cameron went on to bigger and better things and left me completely high and dry. I have since heard that the Tribal Council would be very unlikely to approve of a film project of the nature I was interested in making. Likely, they didn’t approve of the film and Cameron Cuch didn’t have the courage to tell me. The Ute Indians are very protective of their reservation and many of them are not open to outsiders. It could have been that what my film would have revealed would have exposed how dire their situation is despite the enormous amounts of government subsidies tribal members receive. It is sad that this fact still remains despite my effort to use this film as a bridge to help educate fellow Utahns in the misrepresented history of the Ute Indians and the plight that so many have suffered because of their unwillingness to embrace “the white world.”

The Utes are doing better today in allowing businesses to establish satellites with workers on the reservation. There are many efforts in helping kids realize the potential they can reach by receiving a higher education. And the Unitah River Charter School continues to be a success in offering drop-outs a second chance.