A famous experiment: isolate a rat in a cage and give him a choice between water and water laced with cocaine; eventually the rat will stop drinking healthy water and overdose on cocaine water. This experiment was repeated in the 1950s and it developed our modern theory of addiction proving that cocaine and other narcotics are irresistibly addictive. This experiment made headlines in the mainstream media and the public consciousness, it also contributed to modern drug policy prohibiting addictive drugs such as opioids and narcotics.

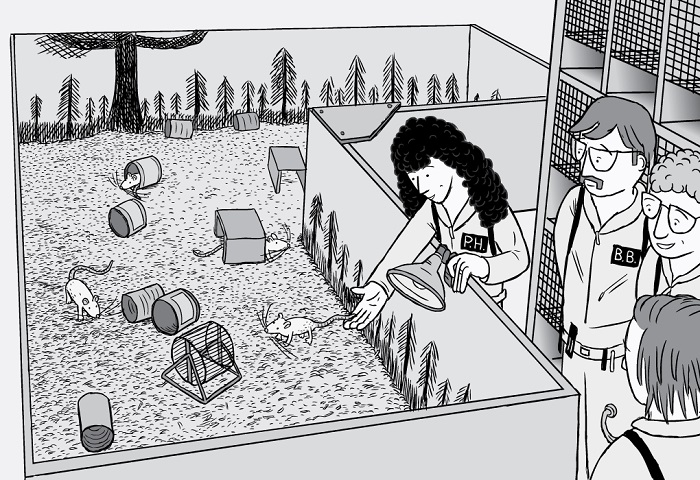

Then in 1979 a researcher named Bruce Alexander and colleagues from Simon Fraser University came up with a spin on the famous experiment: instead of a cage they created a Rat Park, in which the rats, rather than isolated—which they never are naturally—were given a nice social space with toys, platforms, green trees painted on the sides of their park to give them a feeling of space and a natural environment. The results of this experiment destroyed the theory of drug addiction. In a more natural environment, given the choice between the water and the water with drugs, the rats chose food and water rather than an overdose on drugs. “Addiction isn’t you — it’s the cage you live in,” Alexander concluded.

While this experiment was highly significant, the findings never appeared on the front page of newspapers, nor did the major discovery ever even gain traction in the departments of psychology at universities. In fact there are several articles pointing out to the “flaws” in the study. Mainly that it promoted the ideas that we should go easy on criminal addicts.

Why were this study and its findings attacked? Because modern psychology promotes the concept that your brain is an entity in and-of-itself and if it’s sick then it must need fixing. Adding the variable of surroundings to the equation distracts from the modern pharmaceutical-driven paradigm for treatment.

Still, I find the experiment hugely important because of its implications outside of the drug addiction discussion which is: If we create pleasing and beautiful spaces we are less susceptible to depression-fueled addiction.

We are currently facing a growing opioid epidemic as more people are behaving like the rats when introduced to cocaine. But how much of addiction and addictive tendencies are caused by isolation and poor environments? Before researchers attempt to answer this question we can do something that can create a significant change in our lives: improve our surroundings.

What if we added some pottery, wood carvings and plants? What about some nice oil paintings that inspire a good mood? On a greater level, why not create more parks and put a higher value of open space to create healthier cities and neighborhoods?

It’s interesting that the disciplines of psychology and social psychology have not collaborated much with interior design, architecture and city planning. Given these findings why aren’t depressed patients offered a few solutions to making their interiors more mood enhancing?

It was this series of questions which lead to the theme of this month’s issue. Examining spaces that help people to be more productive, social and less neurotic.

Hopefully, by learning from these people we can all become a little more like the rats that chose life and nutrition over stimulus and drugs. Try taking a few good tips from the experts in this issue, write us about your thoughts on space to Richard@UtahStories.com, or share your awesome interior with us on Instagram using the hashtag “#UtahRadSpace.